Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

Her first album in eight years: the singer-songwriter’s captivating

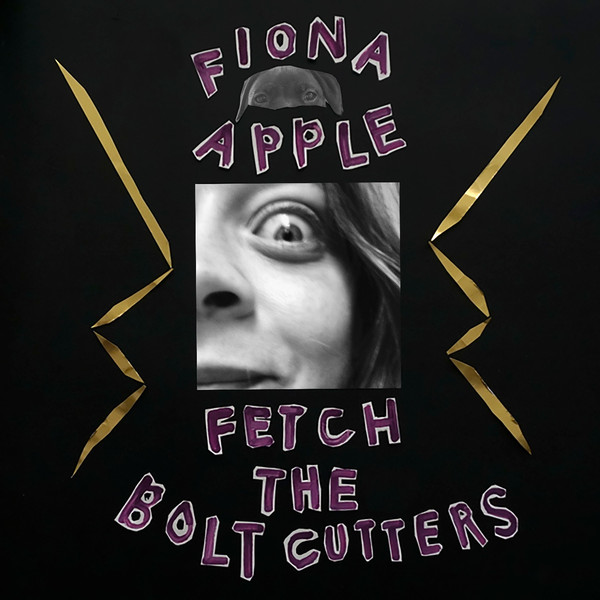

Fetch the Bolt Cutters.

Fetch the Bolt Cutters, by Fiona Apple, Epic

• • •

How much of pop music is really just one big tantrum? Singers moaning about lost loves, guitars that wail and beats that pound: these are the noises that have dominated American culture since the dawn of rock and roll. The goal of most pop musicians is to transcend the constraints they lament, to project some sense of triumph over them—and it’s here that Fiona Apple has always set herself apart. She’s the rare contemporary rock star unafraid of wallowing in her humiliation and insecurity, of getting egg on her face and letting it stay there. Confessional singer-songwriters tend to romanticize their own vulnerabilities, but very few are as willing to risk being dismissed as juvenile or overwrought.

Since emotional expression is invariably viewed through the lens of gender, the stakes are all the higher for a woman like Apple, who has never completely shed the angst of a teenager learning that the world is not what it should be. But through the depth of her artistry, her work defiantly legitimates those righteous hurts we’re taught to hurry up and grow out of.

The sounds and words Apple has been drawn to over the past twenty-four years have nurtured her connection to a young person’s worldview: there are the slam-poetry-like self-assertions (“this mind, this body, and this voice cannot be stifled by your deviant ways,” she declared on her 1996 debut, Tidal, released when she was eighteen); the cheerleader chants and jump-rope rhymes; the whimsical flourishes that lend some of her gloomiest songs an air of being performed in a fun house. These ingredients are woven together by a musical sensibility that has been bold and genre-agnostic from the start, one that continues to make room for both her foot-dragging perfectionism—seemingly the culprit of those long silences that torment her fans—and her delight in trial and error.

Apple’s first album in eight years, Fetch the Bolt Cutters leans into the latter tendency almost to the point of recklessness. The opening track is called “I Want You to Love Me,” which sounds like an assurance that we’ll be reunited with the same sad, spurned Fiona we’ve come to know so well. A snappy percussive intro is followed by cascading piano and a softly articulated vocal—so far, so familiar. But about a minute in, this modest plea for devotion begins unraveling like a ball of yarn. Apple elongates the “you” of the title across several agonizing measures, letting the note curdle in our ears. On the second verse, she attacks the word “want” with the monotony of a child whining for a toy. This is the type of song Apple could have prettified in her sleep; the plaintive elegance of its initial moments calls to mind gorgeous ballads like 1999’s “Love Ridden” and 2005’s “Parting Gift.” The song ends, though, with more than ten seconds of wordless squawking and squealing.

Pop history is filled with geniuses who got impatient with radio-ready formulas and so stretched out into less traditional territory. One could rattle off any number of albums that share a kinship with Fetch the Bolt Cutters’ unruliness: Laura Nyro’s New York Tendaberry, Joni Mitchell’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear. Apple spends nearly a third of this new work going down detours and willfully getting lost, and the results range from the pell-mell exhilaration of “Shameika,” a grade-school reminiscence fueled by some of Apple’s most ferocious piano playing, to the ultimately rather boring rambles on the title track, a freestyle hodgepodge of human whispers and dog barks. That this is the first Apple album recorded largely at the singer’s Venice Beach home, with many of the songs featuring just three other band members (Amy Aileen Wood, Sebastian Steinberg, and David Garza), has already given rise to a host of quarantine-themed think pieces. But this music wasn’t generated in a state of apocalyptic entrapment and deprivation. For Apple, these limitations only highlight the plenitude of her own domestic universe.

The looser songs unfold as if they’re charting some mysterious path from kitchen to bedroom to backyard, with every surface offering itself up as a drum to be banged on. A student of Tin Pan Alley, Apple has a knack for making tunes that, even at their most experimental, have a high degree of shapeliness and polish—but that approach is all but absent here. It’s a testament to her ironclad pop instincts that, amid this dearth of airtight melodies, she’s emerged with a record packed with earworms. When the music really starts to soar, on track five (the maddeningly catchy “Relay”), it strikes a balance between sonic density—built from layers of clanging percussion and compulsive, sometimes blisteringly funny verbiage—and conceptual simplicity. The euphoria this combination induces sustains itself through the rest of the album, which gets palpably more interesting with each passing minute.

Eschewing fleshed-out choruses, Apple creates refrains from phrases, hummed riffs, and, in the case of “Ladies,” a single word repeated ad nauseum. In one three- or four-minute song, she’ll have turned this clump of syllables inside out, like an actor searching for the most effective line delivery (both of her parents were Broadway performers). She tries it in one octave and then another; first precisely enunciated, then slack-jawed; unadorned, then overlaid with harmonies; sometimes with feeling and sometimes with none. On “Under the Table,” she seems to be figuring out the melody in real time, as though each pitch were a stairstep materializing before her eyes. Her contralto has always been a rich, stormy instrument, but here she wields it with a lack of vanity, bouncing between bellows and chirps, bluesy belts and raspy screams. The collage she makes out of these vocal effusions complements the album’s spirit of resourcefulness—she’s using everything she’s got, and she’s having a lot of fun doing it.

The joy of Fetch the Bolt Cutters extends beyond the span of its fifty-one-minute song cycle. The album might inspire you to relisten to Apple’s discography from start to finish, which is easy partly because she’s resolutely unprolific, and partly because so much of it is so good. What this rearview reveals is a master tantrum-thrower who has never stopped looking for new nuances within an old vocabulary of rage. Unlike her previous albums, there’s not a lot of standard wound-licking here, none of what Frank Sinatra would call “suicide songs.” And in most of the best tracks, some kind of reconciliation is being endeavored: on “Newspaper,” it’s between two women acquainted through the same scumbag; on “Cosmonauts,” it’s between lovers weighed down by their shared past; on “Heavy Balloon,” it’s with her own embattled mind. Women who become avatars for our collective pain aren’t often allowed to say that things could get better; if they do, they’re deemed sellouts. Nevertheless, after years of mercilessly sizing up her and everyone else’s scars, Apple is telling us that there’s just as much drama in trying, however stumblingly, to be happy.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.