Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

From Richard Nixon to fading love: Motown releases a collection of the singer’s early 1970s work.

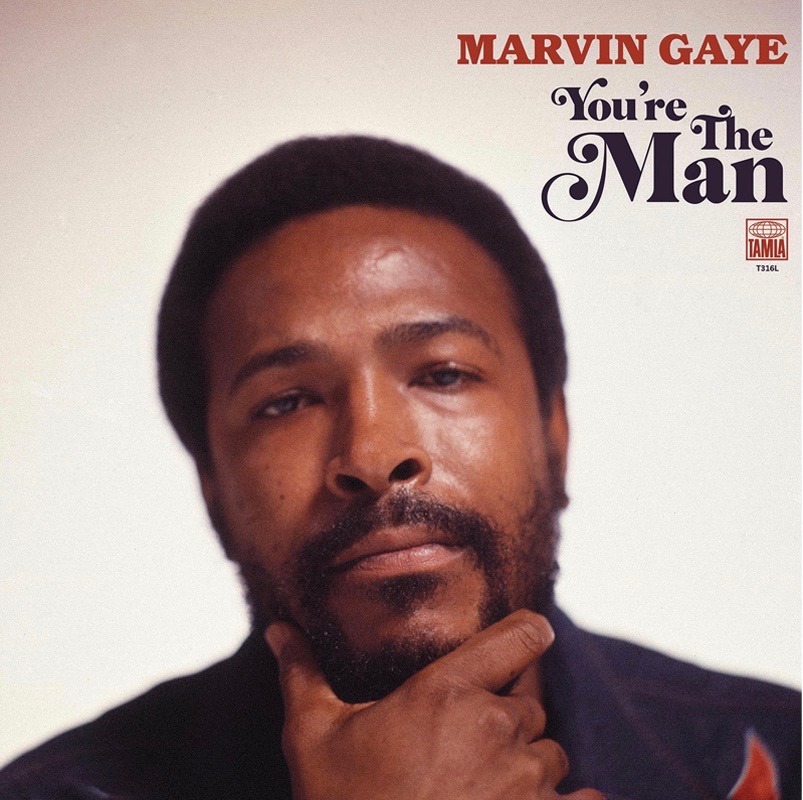

You’re the Man, by Marvin Gaye, Motown Records

• • •

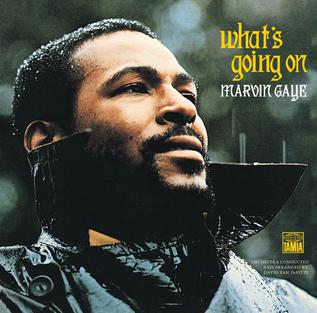

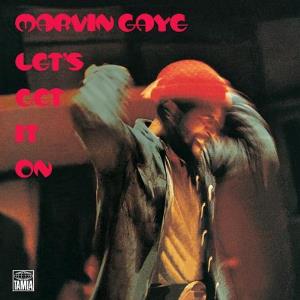

The world wanted Marvin Gaye the lover. And so throughout the R & B star’s career we got variations of that persona: the crooner of prom-ready rhapsodies like “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You)” in the 1960s; the community uplifter of What’s Going On (1971); and the lothario of Let’s Get It On (1973), I Want You (1976), and Midnight Love (1982). Along the way, Gaye also earned a reputation as a deeply troubled soul, but it’s the open-hearted, sex-positive version of him that tends to get memorialized, as in Charlie Puth and Meghan Trainor’s 2015 hit “Marvin Gaye,” a bland homage that invokes his name to describe what otherwise sounds like a chaste night in bed (“let’s Marvin Gaye and get it on”). If that’s what he represents for most contemporary listeners, then the opener of the posthumous collection You’re the Man—just released by Motown Records—comes as something of a reintroduction, showing us that no one could do contempt quite like he did.

“You’re the Man—Parts I & II” was the first single Gaye dropped after What’s Going On transformed him from dependable hit-maker into self-serious auteur in the vein of Brian Wilson. R & B was by that point no stranger to bleakness and cynicism, with acts like Curtis Mayfield and Syl Johnson foregrounding the apocalyptic mood of the era, but the more discursive forms that Gaye gravitated toward on this project were indeed a major shift from his early successes. “You’re the Man” expands on the groove-based approach of What’s Going On and even uses a similar arsenal of sounds—a bongo-infused rhythm section, densely overdubbed vocals that make you feel like you’re overhearing a dialogue in the singer’s head—while also stripping away all the music’s lushness and warmth.

Addressing Richard Nixon just a few months before his reelection, Gaye is sarcastic in a way he’d rarely been before. The melody has the sour, nagging tone of a schoolyard taunt, and the lyrics fling government jargon back in the president’s face. At various points, Gaye digs into the sibilant endings of certain half-rhymed phrases, making them resolve in a hiss: “politics / and hypocrites / is turning us all / into lunatics.” It’s not until his 1978 album Here, My Dear—a caustic account of his separation from his first wife, Anna Gordy Gaye, the sister of Motown founder Berry Gordy—that he would summon this level of rancor again.

Doubling down on his socially conscious diatribes did nothing to get Gaye back into the good graces of his record label, which had initially balked at putting out What’s Going On. So when “You’re the Man” stalled at number fifty on the pop charts, it seemed like the opportune moment for Motown to make a course correction. The company pulled promotion for the song, and Marvin was so wounded by the tepid response that he canceled the album he was developing around it. But more than four decades later, Motown—ever the savvy marketer of its own legacy—has cobbled together the songs that ended up getting scrapped in 1972 into what it’s now touting as a “lost album.” Neither word is very accurate. Though relatively unknown, each track has appeared on at least one of the many compilations the label has issued since Gaye’s death. And as for its status as an “album,” You’re the Man is so obviously lacking in cohesion that it inadvertently shows us what’s so appealing about the two blockbuster LPs it’s purporting to bridge.

Jumping so quickly from the moral urgency of What’s Going On to the R-rated hedonism of Let’s Get It On, Gaye made it simple for us. He boiled his worldview down to a single dialectic, a tug-of-war between conscience and flesh that still forms the basis of his mythology. But because You’re the Man isn’t meticulously crafted to highlight those themes in the way his most ambitious records were, it ends up giving us a looser, much more casual impression of the artist, one less tied down by the symbolic weight of the concept-album format.

Nevertheless, half a dozen of the songs here do showcase Gaye in the political mode one might hope to find in a discarded What’s Going On follow-up. He laments the state of society in “The World Is Rated X,” a wonderfully polyphonic swirl of strings, guitar, and percussion that seems influenced by his film-score work on Trouble Man that same year. In “Piece of Clay,” the squeals of an electric guitar (not a common flourish in his discography) lead into an earnest plea against conformity. Most devastating is “I Want to Come Home for Christmas,” where he continues the character building he began on What’s Going On, singing from the perspective of a prisoner of war with the kind of feverish commitment that could only have been drawn from real pain.

An even larger portion of the track list has nothing to do with social criticism. In these songs, we’re transported back to the sweetheart territory where the world first learned to love Marvin. While none of those tunes have the narrative force or emotional immediacy found in What’s Going On or Let’s Get It On, that hardly makes them any less of a delight for the true Gaye aficionado. Listen closely and you’ll hear some of his subtlest and most beautiful singing—and a few reminders that, in his early days, he had been hell-bent on styling himself after smooth pop balladeers like Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra.

Gaye knew what to do with a nice round vowel, and he flaunts that skill with the open-throated “ahs” and “oos” in “My Last Chance” (retooled here, as are two other tracks, by hip-hop and R & B producer Salaam Remi), so gentle and airy that they seem a universe away from the guttural attack of his heavier material. A pioneer of arranging and layering multiple vocal tracks, Gaye thrilled at drawing as many tonal qualities as possible from his reedy tenor, and You’re the Man gives us plenty of chances to hear the different directions he took his instrument.

The most irresistible cut sits comfortably with the cream of Gaye’s repertoire. A bright and brassy serenade dedicated to a lover he fears is slipping away from him, “I’m Gonna Give You Respect” packs pleasure into nearly every second, with ear-wormy bits of call-and-response and Marvin’s voice moving swaggeringly on and around the beat. Neither as straightforward as his early hits nor as high-concept as his signature work in the ’70s, it’s a perfect fit for a collection of odds and ends like this. While it goes without saying that Gaye’s civic outrage speaks to us as much as ever in our current century, it’s clear from this song—one of his most effervescent hymns to monogamy—that he would have been no less worthy an icon had he only ever sung about matters of the heart.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.