Andrew Chan

Andrew Chan

Lauryn Hill and the enduring musical pleasures of the 1993 sequel.

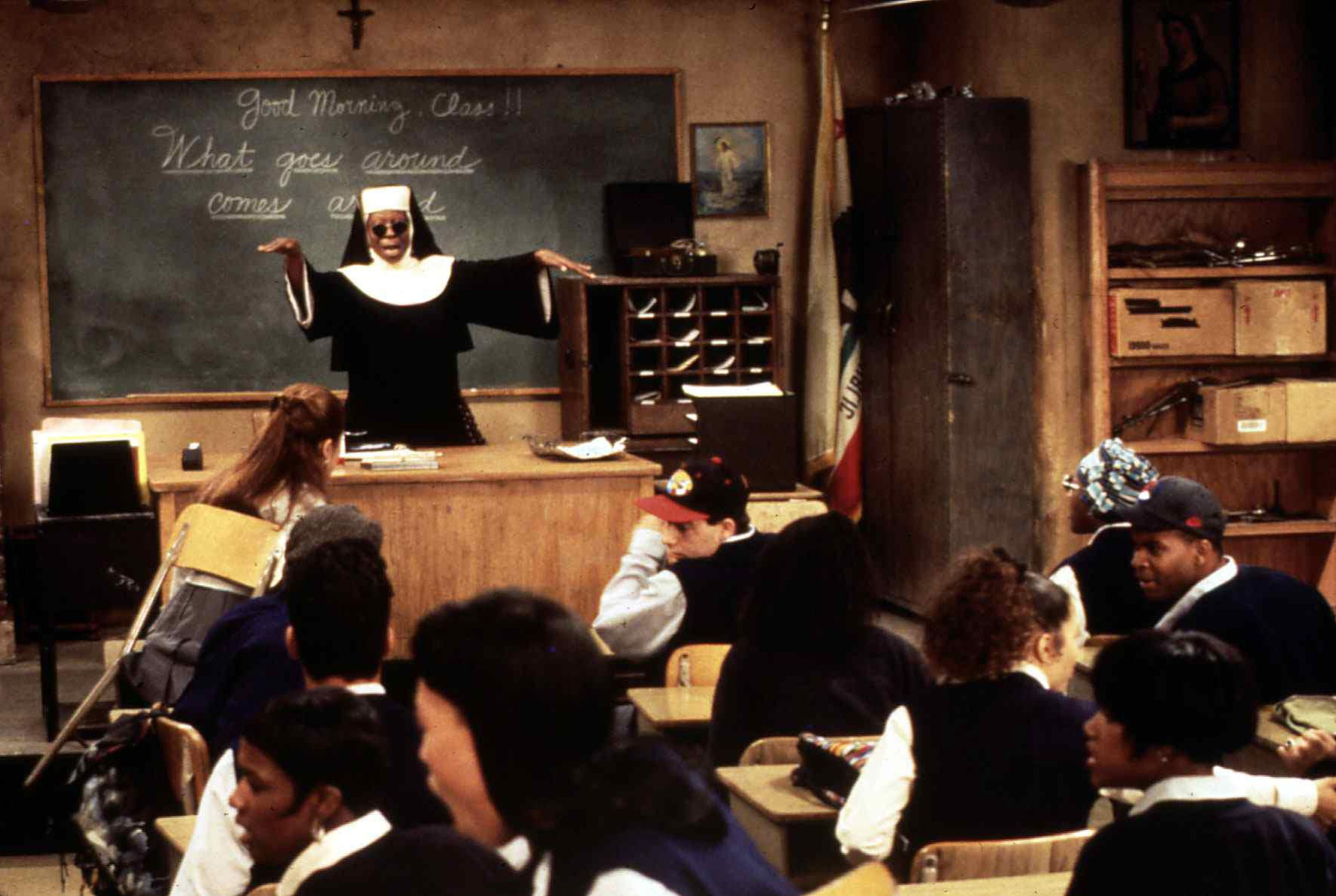

Whoopi Goldberg as Deloris Van Cartier (alias Sister Mary Clarence) in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit. © 1993 Touchstone Pictures. Photo: Suzanne Hanover.

Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit, directed by Bill Duke, available to buy or rent on all major streaming platforms

• • •

Editor’s note: In light of the fact that movie theaters in New York City, where 4Columns is based, and other cities throughout the US remain closed during the coronavirus pandemic, we have invited our contributors to revisit films that are particularly significant to them and that are easily found online.

• • •

It’s not often that a singer gets to stop a movie dead in its tracks. Cinema has curiously never had much use for virtuosic voices, even in the heyday of the Hollywood musical, when Judy Garland was one of the few stars who could captivate an audience for the duration of an entire song without relying on eye-popping choreography or set design. Out of this void, 1993’s Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit has emerged as a singer’s movie for the ages, one with virtually no contemporary rivals. Part of its appeal lies in how lovingly it captures the emotional dimensions of the art in question. Not only is it attentive to the joys of different kinds of singing—private and public, solo and choral, sacred and secular—but it also feels like a film that could have been made only by people who understand on an intuitive level why we sing in the first place.

Whoopi Goldberg may be the top-billed actor here, bringing career-peak charisma to the role of Las Vegas lounge act Deloris Van Cartier, but it’s a precocious, pre-fame Lauryn Hill who steals the show. We meet her character, Rita, as part of a music class that Deloris (alias Sister Mary Clarence) has been tasked with bringing to order at a failing Catholic school in San Francisco. Begrudgingly putting her glamorous life on hold as a favor to her nun friends, who rescued her from a gang of mobsters in the first Sister Act, Deloris sets out to get these unruly teens in line, and Rita’s contemptuous attitude becomes a thorn in her side. It’s not until halfway through the movie that we get to sneak a listen to the problem student’s anointed pipes, a moment that exposes the vulnerability she’s been trying so hard to hide.

Lauryn Hill as Rita in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit. © 1993 Touchstone Pictures.

In a brief but pivotal scene, Rita joins a friend (Tanya Blount) in harmonizing off-the-cuff to “His Eye Is on the Sparrow,” an early-twentieth-century gospel hymn whose lyrics serve as a rousing statement of purpose: “I sing because I’m happy, / and I sing because I’m free.” The words carry a sting of irony because Rita doesn’t seem to be either; she’s in a sullen mood, having just confided that her strict mother thinks singing is “dead-end, no security.” A few lines into the song—which Hill delivers achingly, eyes closed, as if lost in a dream—we can feel what she’s going through: how urgently she depends on music for escape, and how much doubt and shame have built up around her secret talent.

The depth of Rita’s cri de coeur (which anticipates the worldly-wise sensibility Hill would cultivate half a decade later on her classic album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill) gestures toward something weightier than the movie containing it. In many ways, Sister Act 2 is about as slapdash as you’d expect any entry in a mid-tier Hollywood franchise to be, especially one rush-released to bank on its predecessor’s success just a year earlier. In comparison to the first Sister Act, the sequel never really finds its footing as a comedy, and the appeal of watching tough-talking showgirl Deloris chafe at her pious surroundings quickly wears thin. The director, Bill Duke, was fresh off a run of remarkable projects—including the Great Migration drama The Killing Floor (1984), which aired as part of PBS’s American Playhouse, and the stylish neo-noir Deep Cover (1992)—but Sister Act 2 doesn’t neatly lend itself to auteurist consideration; even at its best it’s unmistakably a job for hire. Upon its release, it was a commercial and critical failure.

Barnard Hughes as Father Maurice, James Coburn as Mr. Crisp, and Whoopi Goldberg as Deloris Van Cartier (alias Sister Mary Clarence) in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit. © 1993 Touchstone Pictures. Photo: SNAP.

But not being a masterpiece hasn’t prevented it from becoming a generational touchstone. Beyond providing a showcase for an impressive group of young singers, the movie is a time capsule of aspirational multiculturalism at its height. Its central conflict—a school with a majority-minority student body at risk of being shut down by a heartless white administrator (James Coburn)—takes the racist neglect of the US education system as a given. At the same time, the film’s vision of an interracial harmony brokered through song evokes something utopian at work in the pop culture of the nineties, an era when multiple forms of African American music had so thoroughly saturated mainstream consciousness that the notion of “crossover” was beginning to seem obsolete, fostering the fantasy of one nation under a groove. The contradictions inherent in this social context are lightheartedly implied by the clash of two supporting characters: Ahmal (Ryan Toby), a self-possessed Black student prone to citing pearls of Afrocentric wisdom, and Frankie (Devin Kamin), a white guy whose appropriative flirtations with hip-hop don’t seem to damage his friendships with his classmates of color.

Whoopi Goldberg as Deloris Van Cartier (alias Sister Mary Clarence) and cast in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit. © 1993 Touchstone Pictures. Photo: IFA Film.

As in Richard Linklater’s School of Rock (the 2003 movie that feels most like Sister Act 2’s spiritual progeny), the story culminates with an absurdly high-stakes performance that gives the students a chance to save their school from jeopardy. Deloris’s pedagogical prowess is such that no sooner has she sniffed out talent in her seemingly unpromising charges than she identifies a goal for them to reach and a platform for them to display their gifts: a statewide choir competition. The buildup to this event verges on incoherence; we aren’t given enough time to observe the class rehearsing, a bewildering elision that denies us the pleasure of hearing this group of previously untrained voices find and hone their sound. But by the end, such narrative sloppiness hardly matters.

The scene in which the choir finally hits the stage is as transcendent as any musical number of the past thirty years, and while it may be a mystery how these kids got so professional so fast, the thrill of what they end up pulling off together speaks for itself. Built on an ingeniously maximalist vocal arrangement by Mervyn Warren that mashes up fragments of Beethoven, Janet Jackson, and Naughty by Nature, this climactic showstopper was instrumental in bringing the sounds of the church definitively into the realm of pop, a development that had been underway in the Christian music scene for decades. If Warren’s jukebox approach sounds quainter with the passing years, it may be because a generation of artists like Kirk Franklin, Mary Mary, and B. Slade have made this genre-blending formula even more prevalent in contemporary gospel.

Whoopi Goldberg as Deloris Van Cartier (alias Sister Mary Clarence) and Lauryn Hill as Rita in Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit. © 1993 Touchstone Pictures.

The legacy of Sister Act 2 rests on a handful of moments like this, but its resonance isn’t fleeting or shallow. I think one of the reasons the film has enjoyed such a rich, meme-fueled afterlife is that it’s uncommonly persuasive on the subject of talent: what it’s like to have it, how painful it is to feel obstructed from using it, what it takes to share it with the world, why it can be so moving to witness. Unlike most other cinematic teacher figures, Deloris doesn’t resort to patronizing or tormenting her students to pull their brilliance out of them, because she sees talent as something natural and plentiful. That idea may or may not be borne out in real life, but the movie makes us want to believe it, and leaves us feeling we might be good enough to join in the fun.

Andrew Chan is web editor at the Criterion Collection. He is a frequent contributor to Film Comment and has also written for Reverse Shot, NPR Music, Slant, Wax Poetics, and other publications.