Paul Chan

Paul Chan

A talk given to students enrolled in the Hunter College MFA Program on April 29, 2020.

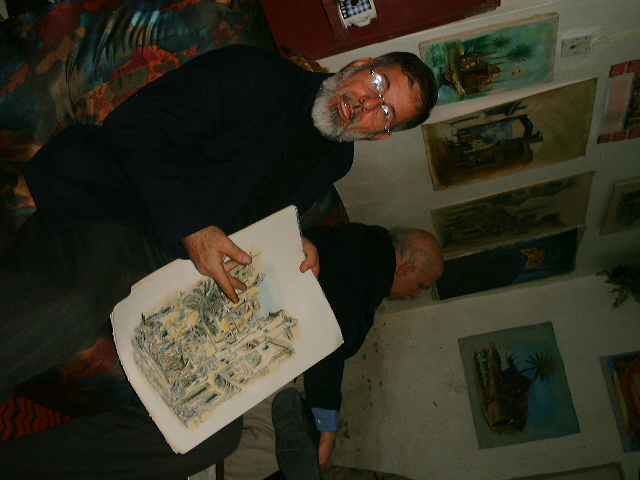

Last days at studio before city shutdown. Image courtesy Paul Chan.

Not being able to go home and being stuck at home are two of the less tragic reasons why these are the worst of times. I find myself in both situations at the moment. I’m stuck here, outside Boston, and can’t get home safely, back to New York.

There are much more dismal situations to be in besides mine. I’m not complaining. In fact, the opposite may be the case. The funny thing about me is that I feel most at home when I’m not at home anywhere in particular.

I don’t assume this feeling fits everyone. There are many different ways of thinking about what it means to be home. Experiences that make the concept of home meaningful are as fluid and varied as our sexual identities.

I’m reminded of a conversation in 2002. I was in Baghdad, drinking tea with an imam a few months before the start of the second gulf war. He asked me casually where I was from. “New York,” I replied. He smiled, then leaned in closer and said, “No, I mean, where are you from?” I took a second. “Hong Kong,” I asserted. “I was born in Hong Kong.” “No,” he said, smiling as he shook his head, “I mean, where are you from?”

Paul Chan, Baghdad In No Particular Order (still), 2003. Single channel video. Image courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

These thoughts are on my mind because a dehumanizing notion of home is being promoted by the most barbaric voices in American life. “We must go back to the way things were as soon as possible,” these voices declare. “The economy must reopen immediately. Businesses must business again. Workers must work again.”

Get sick if you have to. Drink bleach to cope. The meaning of home here speaks to the demand that we must return to how they were most at home with us—as the help, so to speak—for the house they think they rightfully own.

Is it worth returning to the way things were? Is there a direction home that doesn’t point backward? Does the concept and experience of art play a role in any of this? These are the questions I want to consider with you.

• • •

Homer

Paul Chan, Poordysseus, 2018. Nylon, fan, wood, glass. Image courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

One of the most evocative notions of what it means to go home is also one of the oldest. It’s from the ancient Greeks, by way of a work of art. I’m referring to Homer’s Odyssey. The story of The Odyssey is essentially about someone trying desperately to go home, back to where he’s from and how things were.

What he has to endure to get home is what truly matters. This is because how he journeys home is how he gains what the Greeks called Kleos (κλέος), which roughly translates as “renown by rumor.” Kleos was a crucial aspect of what the Greeks thought a good life consisted of. It is what we call today an identity, of being some one as opposed to being no one.

For the Greeks, gaining an identity was synonymous with getting in and out of trouble. Being someone, having Kleos, enriches a life and grounds it in a reality worth belonging to. But having an identity also attracted the wraith of gods and men. This was poignantly expressed in a line from The Odyssey: “There is no way to stand firm on both feet and escape trouble.”

Trouble is what you find and what you must endure if you wish to gain an identity. This is why going home was considered a form of self-expression for Homer and the Greeks. Going home was an artistic medium, like sculpture or painting. This is the dynamic The Odyssey captures. The finest art was life itself composed by an aesthetics of endurance and cunning.

• • •

Rumors

Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, 2007 (Gentilly performance). Image courtesy Paul Chan.

I heard a rumor once about how a mother and child survived Hurricane Katrina in 2005. They were stranded on a rooftop as the floodwater rose. The child knew he was in danger, but wasn’t old enough to make sense of what was endangering him, and why. He became withdrawn, paralyzed with dread.

The mother realized what was happening, but couldn’t stop what threatened them both. So she did the only thing she could: she told him a story. The story was an adventure about two heroes, her and him. The mother recast what was about to engulf them from all sides into an adventure that they—the heroes—had to endure if they were to win the day, and survive.

As the child listened, he gradually became more present and engaged. Nothing changed except how he saw things. But that made all the difference. The child began to cope, and even took some pleasure in helping his mother figure out how to get rescued. He found his wits again, which helped him rekindle the will to be present, and be someone.

How we think about what we’re doing changes how we do it, and ends up reshaping us in the mix. This dynamic, where entities mutually change each other through engagement, is referred to as a species of thinking known philosophically as dialectics.

I learned about dialectics through art. It was the experience of making work that taught me how the work I make remakes me as much as I make it. I feel I’m never quite the same after making what ends up mattering most. This is why I find pleasure in the notion that art is a form of self-expression only if the self is as dynamic and surprising as the expression itself.

The practice of working artists at whatever station in life is, at best, uncertain and precarious. There is no recipe for making good work. But generally, artists learn to recast their lot to suit how they need to express what it means to be someone. Making art is also where artists learn that aesthetics offers more nourishment than mere taste-making, if the practice of making work is treated like an adventure.

• • •

Adventure

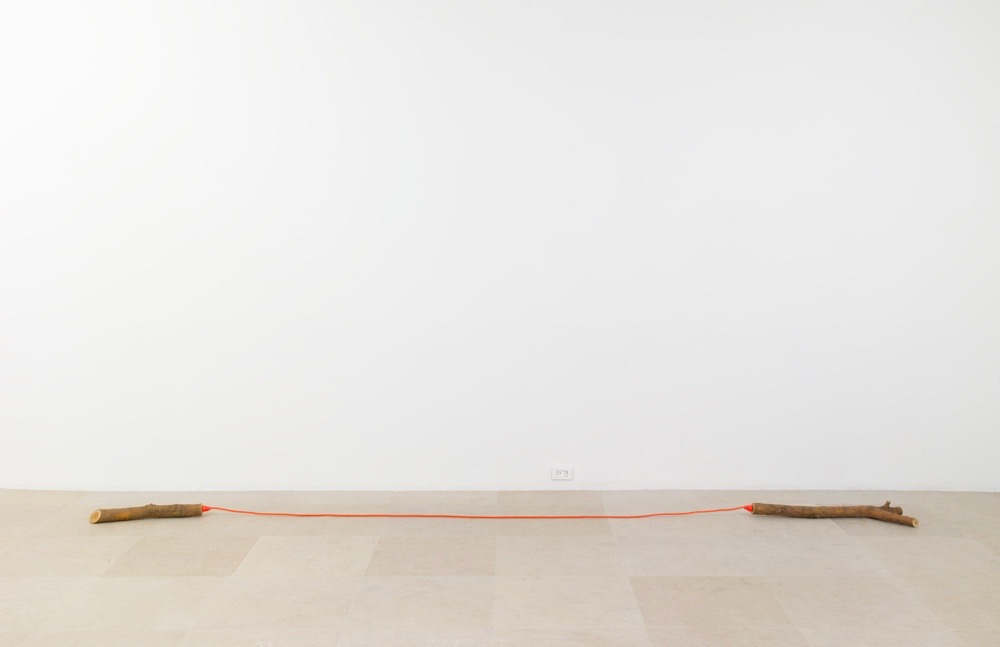

Paul Chan, The Argument: Door, 2012. Mixed media. Image courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali Gallery.

If aesthetics is understood as the discourse we use to judge what is beautiful or worthy of attention, then treating aesthetics like an adventure means discovering what is genuinely beautiful by way of going through something like a process or a reckoning that is by and large unpredictable.

Giorgio Agamben recently wrote a remarkable little book called The Adventure, in which he points out a common thread among great literary adventures in the West from the Middle Ages up to the Renaissance. He shows how the goal of finding that magical sword, or the secret treasure, is never the real concern of the stories.

The heart of the aesthetic matter is instead how the protagonists gain new senses of themselves as they journey to reach the goal. The thing, the goal, is simply used to reawaken the wonder, courage, and resilience it takes to be fully present in the face of all that is hostile and indifferent.

Agamben also suggests that the adventure as a literary form was intentionally marginalized by Christendom during the Middle Ages. Stories that promoted the excitement and pleasure of people thinking and judging for themselves to make sense of what is challenging and unpredictable did not vibe with an expanding religious empire that depended on obedience for its growth and prosperity.

Treating aesthetics as if it were an adventure helps us resist the temptation of accepting whatever authority deems as beautiful or worthy, just because it is official or sanctioned. A genuine aesthetics is, broadly speaking, one where other choices become possible as routes to finding what is right or beautiful, beyond what is evident or given.

The art of living may depend on whether one is willing to live as if it were an adventure.

• • •

Origin

Paul Chan, Katabasis, 2019. Mixed media. Image courtesy the artist and and Greene Naftali Gallery.

Every adventure is motivated by a goal. Odysseus, the main character in The Odyssey, wanted to go home. The mother and child in New Orleans wanted to be rescued. We want to survive this global pandemic.

One of the most paradoxical phrases penned by the great Viennese writer Karl Kraus was this: “The origin is the goal.” It’s not hard to recognize how conservative the phrase sounds. Kraus was in fact deeply conservative, and during the early twentieth century, he brilliantly and mercilessly criticized how the advent of modernity was degrading the language and culture of his native Austria.

“The origin is the goal” can be read as a motto for what Kraus believed was the proper goal for any endeavor, cultural or otherwise: to return to a glorious bygone past. All the Good Ole’ Boys today calling for an end to the policies that have saved people from dying and suffering would feel at home with Kraus, I’m sure. They prefer we die by savage inequalities, like the Good Ole’ Days, than be killed by any novel virus.

But Kraus was more than merely conservative. He was also an exemplary artist. He composed poetry and prose that can be read in varying, even opposing ways, without the words ever losing their precision, intensity, or wit.

“The origin is the goal” is no different. Notice how it’s possible to read the word “origin” as more than what is at root or source. “Origin” can also refer to something beginning—in other words, something that is new. Understood this way, the entire phrase is radically transformed, without a single word changing. The goal is now not to go back to a past. The goal is to find or discover what is new. Better yet, to find what is worth beginning anew.

Kraus was arguably not opposed to the future: he was against dogma and morons. I don’t know the future. I’m not here to tell you how this is all going to end. It may not. I came to tell you that what is new in art is a reminder of what is worth renewing in life. And that what is new in art, and what is worth renewing in life, may depend on cultivating an aesthetic sensibility capable of recasting what troubles us into a plot that is pleasing or interesting enough to warrant our undivided focus and participation.

This is how a genuine work is made. This is how a day is won, and an identity is gained. This is how someone endures. How this is done in an era more punishing than any in recent memory is almost impossible to grasp. But is it also impossible to imagine? Being an artist today may simply hinge on whether this question is taken up.

The answer, of course, is not the important part.

Paul Chan is an artist who lives in New York. His work has been exhibited widely in many international shows, and he is the winner of the 2014 Hugo Boss Prize. His essays and interviews have appeared in Artforum, Frieze, Flash Art, October, Texte Zur Kunst, Bomb, and other magazines and journals. He is the editor and artist for the forthcoming Word Book by Ludwig Wittgenstein (Badlands Unlimited, 2020).