Noah Chasin

Noah Chasin

It’s a total blam-blam: the Brooklyn Museum hosts an immersive exhibition of the iconic musician’s artifacts.

The Archer, Station to Station tour, 1976. Photo: John Robert Rowlands. © John Robert Rowlands.

David Bowie Is, the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, through July 15, 2018

• • •

My reviewer’s copy of the exhibition catalogue for David Bowie Is arrived before I’d seen the show. I hungrily ripped it open, looking forward to . . . what, exactly? How does one dare capture the Bowie spectacle in two inanimate dimensions? The tome in front of me proved the futility of such an effort. As a quick read through revealed, the book renders the life of this most chameleonic of musical illusionists dull and inert: costumes draped unresponsively on headless mannequins and photographed against flat white backdrops; a collection of personal ephemera too stiflingly totemic (these include a Space Oddity–era twelve-string guitar, a 1975 life mask, pages of handwritten notes and lyrics, illustrated storyboards for the Diamond Dogs tour stage set, posters, playbills, and a pink stuffed dog from the 1979 Saturday Night Live performance of “TVC15”). I came to fear that the exhibition—which originated at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum in March 2013 and is making its final stop at the Brooklyn Museum—would likewise represent a similarly dry recitation of the Bowie narrative.

Stage set model for the Diamond Dogs tour, 1974. Designed by Jules Fisher and Mark Ravitz. Courtesy the David Bowie Archive. Image © Victoria and Albert Museum.

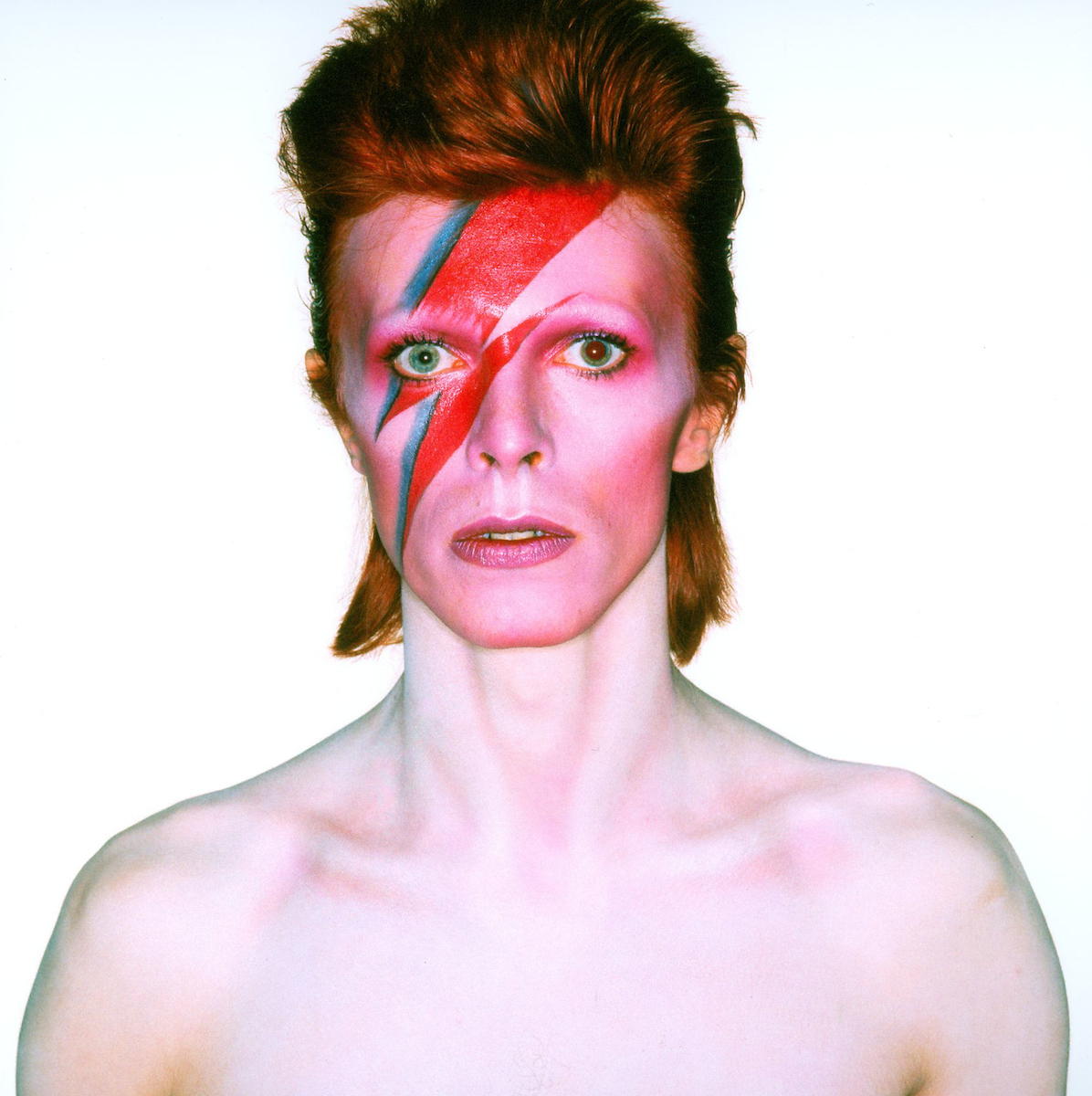

To be fair, I first learned about Bowie from a book, one of those Time Life History of Rock publications that appeared in my childhood home in the mid-1970s. (Bowie had a knack for showing up very much unexpectedly; although this instance might have had something to do with Sheila Bell, our au pair from Bournemouth, England.) We were a classical music–only household; the closest thing we had to pop music was Jacques Brel. Bowie being so much more exotic, I spent hours poring over the photos of this androgynous creature who, despite wearing women’s clothing and makeup, had both a wife (Angela) and a son (Zowie). I had no soundtrack to the pictures, so I had to conjure up what it would be like to attend his concerts or relish the joys of his album Aladdin Sane.

Photograph from the album cover shoot for Aladdin Sane, 1973. Photo: Duffy. © Duffy Archive & the David Bowie Archive.

My discovery of punk rock is the only reasonable explanation for why it took another decade for me to finally do a close listen to Bowie’s music. From then on he has haunted my life, punctuating occasions both epic and trivial—here cementing a friendship, there consecrating love, everywhere providing a sense of discovery and of beguilement.

The Brooklyn Museum scored a great coup in being able to present David Bowie Is. The hype around the exhibition has been perhaps more fevered in NYC than at any of its previous venues; Bowie lived out his life’s final chapters in the Big Apple, and the city eagerly claimed him as its own. The plan was always for the exhibition to end in New York, but no one anticipated the same to be true of David Bowie. His last, masterful album (Blackstar) dropped on January 8, 2016, his sixty-ninth birthday. Bowie died two days later, inaugurating an annus horribilis for rock ’n’ roll, the country, and the world. The show, however, had to go on.

Queue up, clap on your complimentary headset, and cross the threshold into the exhibition. Any drabness one might have feared based on the catalogue gives way to a truly immersive experience—as good a realization of “Sound and Vision” as one could hope for. The iPod-sized transponder slung over your shoulder syncs up nearly flawlessly with the audio of television broadcasts, movie clips, and, above all, concert and video footage. I found something positively thrilling in listening to “Starman” while reading Bowie’s careful script on the original lyric sheet. One can’t help but give oneself over to the sheer pleasure of this carnivalesque spectacle. I watched elementary-aged kids being led around by their parents and saw them marveling, as did I when I was their age, as they tried to make sense of this pan-gendered, cyborgian, shapeshifting creature.

David Bowie Is, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum.

The costumes appear on mannequins similar to those in the catalogue, but now mostly with heads that, in some cases, feature what appear to be metallic death masks of the man himself—a foretelling of the show’s sad dénouement just around the corner. It’s hard to escape the knowledge that Bowie died before the show completed its run. But before encountering the discomfiting bandage Bowie wore across his face in the wonderfully excruciating video for the track “Lazarus” from his final album, one enters a room with floor-to-ceiling screens showing archival footage of the artist onstage. Sound blasts from speakers—headphones no longer necessary—conjuring a very effective simulation of a live performance.

David Bowie Is, installation view. Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum.

Some Bowie narratives suggest that his successes accrued in spite of his legendary (and occasionally apocryphal) transgressions and indulgences—whether sexual (Lindsay Kemp, Lou Reed, Elizabeth Taylor), chemical (cocaine, cigarettes), theatrical (Just a Gigolo), sartorial (Armani’s Seinfeld-esque pirate shirt of 1990), orthodontic (his flirtations with cosmetic dentistry betrayed an awkwardness at odds with his legendary bravado), and even musical (Never Let Me Down, Hours). My most valuable takeaway is that he remained, perhaps miraculously, always in control, keen to maintain a hand on the rudder even if the ship was veering into a storm. Nowhere is this clearer than in his decision to keep his impending death from the public while making Blackstar.

Bowie’s father was an erstwhile nightclub owner; his mother worked in a cinema. Their son was, as they say, born to the stage, intent on exceeding his parents’ modest encounters with showbiz fame. He never wavered from the course he’d set for himself within the storied tradition of stagecraft; as he told a reporter in 1972: “I’m out to bloody well entertain, not just get up onstage and knock out a few songs.” A flair for theatrical narrative seems to have imbued everything he did, up to and including his last days. In a move that surprised everyone, though in retrospect seemed inevitable, with his final album Bowie wrote his own valediction and eulogy, then disappeared just as the waves crashed over the bow, vanishing elegantly into that black-starred night.

Noah Chasin writes on the intersection of human rights and the built environment in twenty-first-century urbanization. He teaches the history and theory of Urban Design at Columbia University, where he is also affiliated faculty at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights, and at the New School. He is Executive Editor at the Drawing Center.