Noah Chasin

Noah Chasin

Architecture with a green agenda: MoMA surveys a half century of sustainably minded built-environment projects.

Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, curated by Carson Chan with Matthew Wagstaffe, Dewi Tan, and Eva Lavranou, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street,

through January 20, 2024

• • •

“Placing a building on the earth—on our earth—it’s a big responsibility.” So cautions architect Jeanne Gang in one of seven recorded commentaries found throughout Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism. The exhibition grapples with this admonition’s gravity via more than 150 projects that respond to the perils of climate change with visions for a sustainable and adaptable built environment. Perhaps to underscore the seriousness of such an effort, curator Carson Chan and his team have conjured an almost scientific mood in the Museum of Modern Art’s third-floor galleries, as if transporting visitors to the Museum of Natural History—the spaces are darkened, the drawings and models spotlit.

Glen Small, Biomorphic Biosphere. Project. Drawing of a flying house, 1973. Pen and watercolor on paper, 19 × 24 inches. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Apart from a few precursors, the works on view were made in the wake of the environmental crisis of the 1960s and ’70s. It’s seductive to see the inventiveness with which architects confronted the dawning realization that humankind’s extractive and acquisitive tendencies were both assaulting and depleting the earth. Some, such as Carolyn Dry, turned to what is known today as biomimicry. Her study drawings for military ports (1980) are inspired by the underwater grottoes formed by corals and other submarine bodies, the logic being that bioorganic construction, refined for millennia through biotic trial and error, results in far more resilient structures than those technologically devised by humans. Other designers sought to leverage alternative forms of energy, such as the solar-powered—and thus autonomous—experimental collective housing projects (1974–85) by the Cape Cod–based New Alchemy Institute, displayed here through drawings. Also noteworthy is a house in Dover, Massachusetts, by Mária Telkes and Eleanor Raymond (1948), designed in response to postwar concerns about the US’s energy independence. As we see in both period photos and a newly commissioned model, the entire second story is hung with double-paned panels intended to gather solar energy and disperse it through the house via fans and heat bins—a system that, while ingenious, ultimately failed to meet its technical ambitions.

Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured, center top: Eleanor Raymond and Mária Telkes at the Dover Sun House, Dover, Massachusetts, 1948. Lower right, on plinth: Model reproduction of Dover Sun House, Dover, Massachusetts, commissioned 2023.

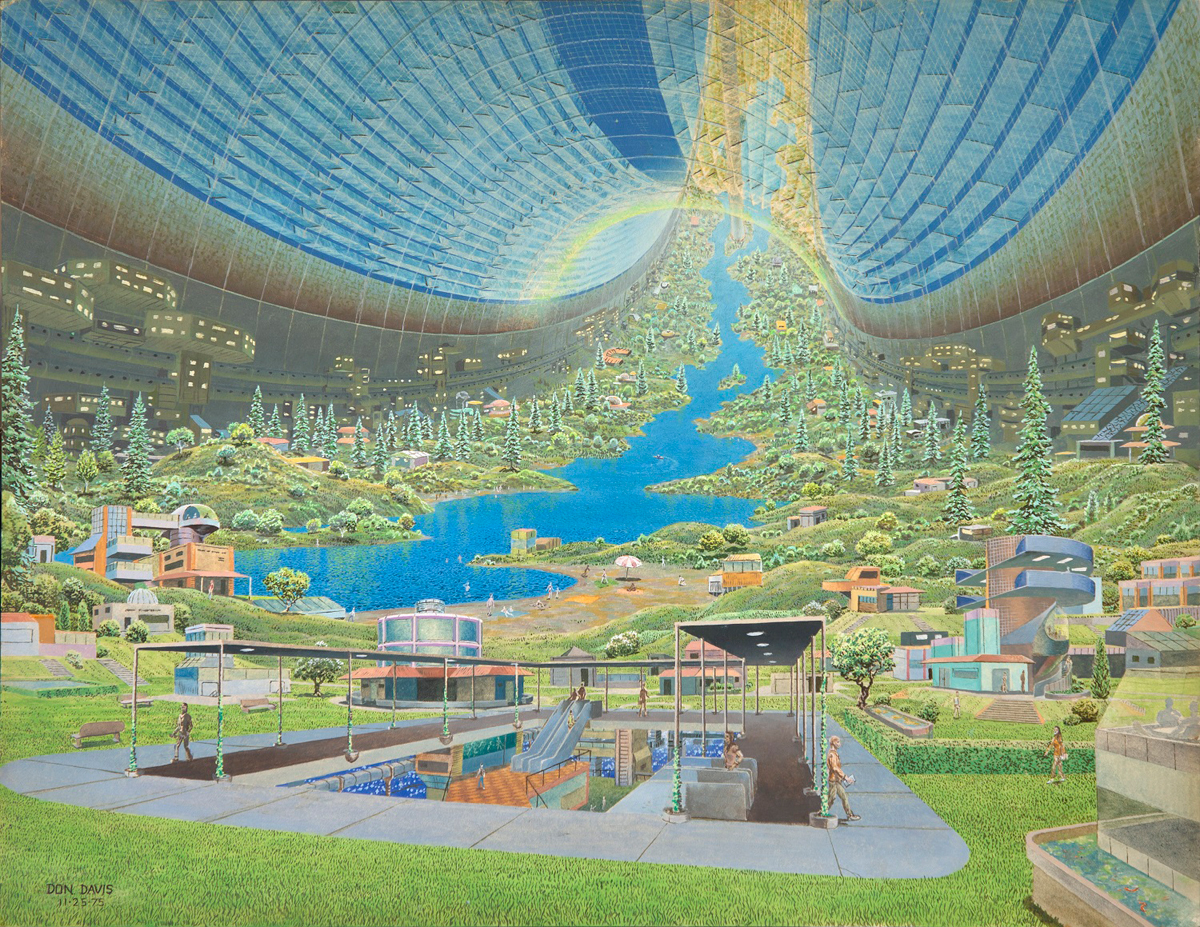

While those mentioned above attempted small-scale interventions, NASA deployed its vast resources toward terraforming, another now-common buzzword. The results exemplify the speculative turn that became another strategy for neutralizing anxieties around a changing climate. The Stanford torus (1976) and the Bernal sphere (1975) appear in vivid acrylic paintings depicting these self-contained space colonies adrift in deep black space; dispiritingly, they seem as implausible today as they would have been fifty years ago.

Don Davis, Stanford torus interior view, 1975. Acrylic on board, 17 × 22 inches. Courtesy Collection Don Davis.

It’s difficult to foresee tangible results from many of the exhibition’s dreamily idealistic projects. Even a sympathetic viewer would be forgiven for asking: “Sixty years in, and architects still haven’t had much success in minimizing the built environment’s carbon footprint, have they?” The curators are aware of these deficiencies. Chan writes in the catalog: “The hope is that this book, as an inventory of the show’s material, will become a resource for those interested in tracing a new path for architecture that puts ecological and environmental concerns before all other considerations.” I do not doubt that most of the proposals on display were conceived as earnest attempts to get ahead of mounting fears concerning future ecological stability. The show’s most poignant moments, however, occur when harsh reality punctures the languor of these reveries. For example, Black and Brown bodies were (and are) too often overlooked as the collateral damage of this exploratory environmentalism. A disappointingly perfunctory glance at environmental justice initiatives—photographs and flyers from the 1982 protests in Warren County, North Carolina, over a proposed PCB landfill from the late 1970s, along with material documenting the Yavapai Nation’s march to the Arizona State Capitol (1981) to prevent the construction of the Orme Dam—brings the visitor back to the inconvenient truth lying beneath tech-heavy eco-modernism.

Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured, center left: Protesters marching against a PCB landfill in Afton, Warren County, North Carolina, led by Reverend Leon White (second from left), Reverend Joseph Lowery (center), and Ken Ferruccio (second from right), 1982. Courtesy Getty Images, Bettmann Archive. Photo: Otto Ludwig Bettmann.

One of the exhibition’s unheralded strengths lies in its revelation of the disproportionate number of female architects and designers involved in various ecological and environmental remediation projects. This fact should come as no surprise—women around the world involuntarily shoulder the burden of responsibility regarding environmental issues. Their noteworthy contributions to ecologically and environmentally minded projects are not coincidental, and I wish the curators had highlighted this fact more forcefully.

Anna Halprin and Lawrence Halprin, Experiments in Environment Workshops, Participants in the Sea Ranch Driftwood Village Rebuilt event, Sea Ranch, California, 1968. Courtesy University of Pennsylvania, the Architectural Archives.

According to statistics from the American Institute of Architects, women comprised but 1 percent of all practicing architects in 1958. By 1999, the number had risen to a mere 13.5 percent. Today, the number is somewhere around 20 percent and is in its ascendancy, but the discipline has a long way to go before redressing centuries of gender inequity. By contrast, nearly 46 percent of the projects included in Emerging Ecologies were partially or fully designed by women. Yet even those conversant in the recent history of ecological architecture and urbanism will find many of their names unfamiliar. Phyllis Birkby, Anna Halprin, Margaret Howe Lovatt, Nancy Jack Todd, and Beverly Willis all deserve greater esteem in a corrective retelling of this history. They were standard-bearers among the ranks of those designers who felt an ethical responsibility to plan conscientiously for an uncertain future.

Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

If the important role played by women in environmentally oriented architecture is this exhibition’s subtext, the more prominent agenda is to inaugurate the Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment at MoMA. Ambasz, a widely revered and highly enigmatic architect, has a long history with the museum, having served as its design curator from 1969 to 1976 and then as a generous patron. Notably, he is also often hailed as a pioneer of “Green Architecture,” one of many idioms (along with “sustainable,” “ecological,” and “organic”) used to describe architecture’s ethical attempts to meaningfully address the mushrooming climate crisis.

Emilio Ambasz, Prefectural International Hall, Fukuoka, Japan, aerial view, 1990. Courtesy Collection Emilio Ambasz. Photo: Hiromi Watanabe.

Ambasz, despite his commendably prescient insistence that architecture renounce its obsession with buildings as sovereign objects oblivious to their natural surroundings, has never really been a practitioner of what today we think of as environmentally empathetic design. His Lucile Halsell Conservatory (1982) in San Antonio, Texas, leans heavily on the poetic symbiosis between structure and landscape but exhibits little of the designer’s environmental evangelism. This is also true of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Fallingwater (1935) appears early in the exhibit as a harbinger of environmentalist architecture. Predating the postwar onset of aggressive environmental deterioration, the house is better understood as an example of a structure that seeks to coexist in harmony with its surroundings than as one conscientiously designed to minimize—both in construction and usage—the extent to which it consumes energy and materials. In this sense, it exemplifies much of the work assembled in Emerging Ecologies, which collectively, and despite many makers’ intentions, reads as more symbolic than transformative.

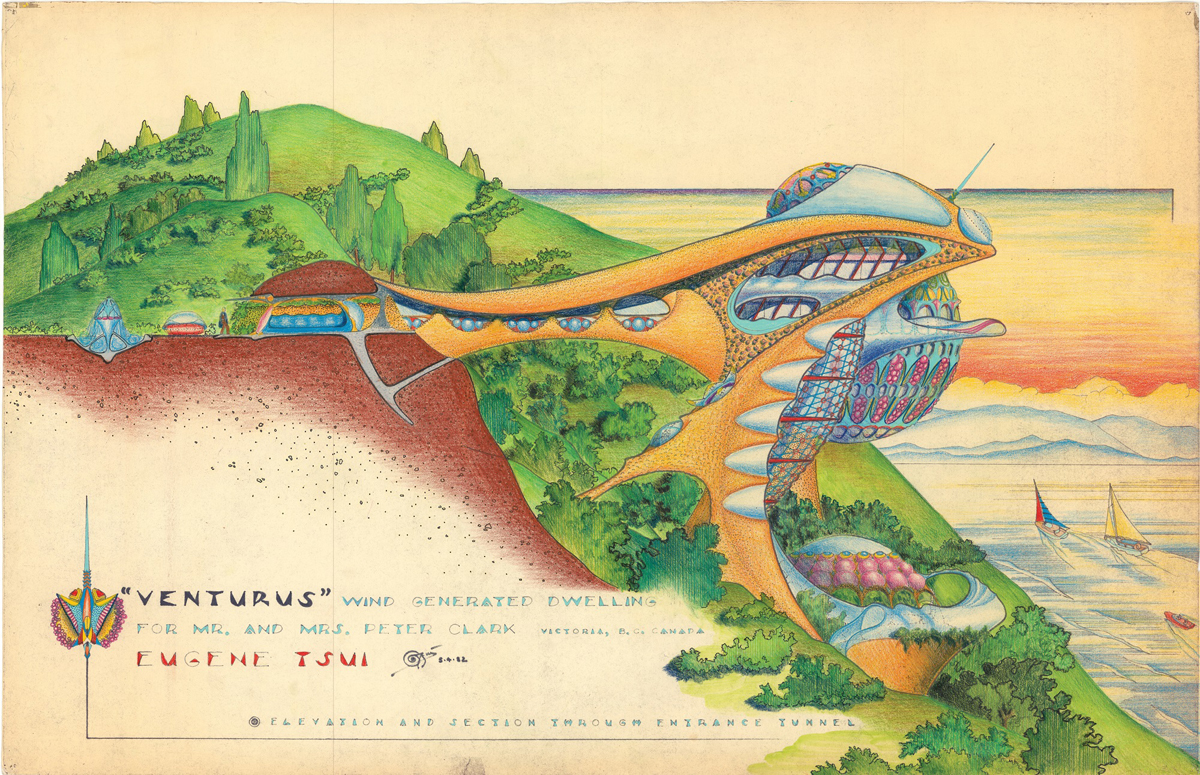

Eugene Tssui, Venturus, wind-generated dwelling for Mr. and Mrs. Peter Cook, Victoria, BC, Canada, 1982. Watercolor, Prismacolor pencil, pastel chalk, and colored ink on paper, 21 × 32 inches. Courtesy Collection Eugene Tssui.

Both the exhibition and its catalog conclude with a timeline matching noteworthy achievements in ecological architecture with major events (both positive and negative) in the environmentalist movement. It begins in 1894, with the founding of the American Society of Heating and Ventilation Engineers, and concludes in 2000, with Paul Crutzen’s coinage of the “Anthropocene.” His radical proposal, following the scientific consensus that the earth’s systems have been irreversibly changed through irresponsible human activity, argues that the planet has entered a new epoch for the first time in nearly twelve thousand years. Chan’s stated ambition is to lay the foundation for future efforts that will respond more urgently to the alarmingly exponential changes to our ecosystems. That work begins now.

Noah Chasin writes on the intersection of human rights and the built environment in twenty-first-century urbanization. He teaches the history and theory of urban design at Columbia University’s GSAPP, where he is also affiliated faculty at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights.