Noah Chasin

Noah Chasin

Reagan, Robin, and baseball: all are skewered by the irreverent artist in his New Museum retrospective.

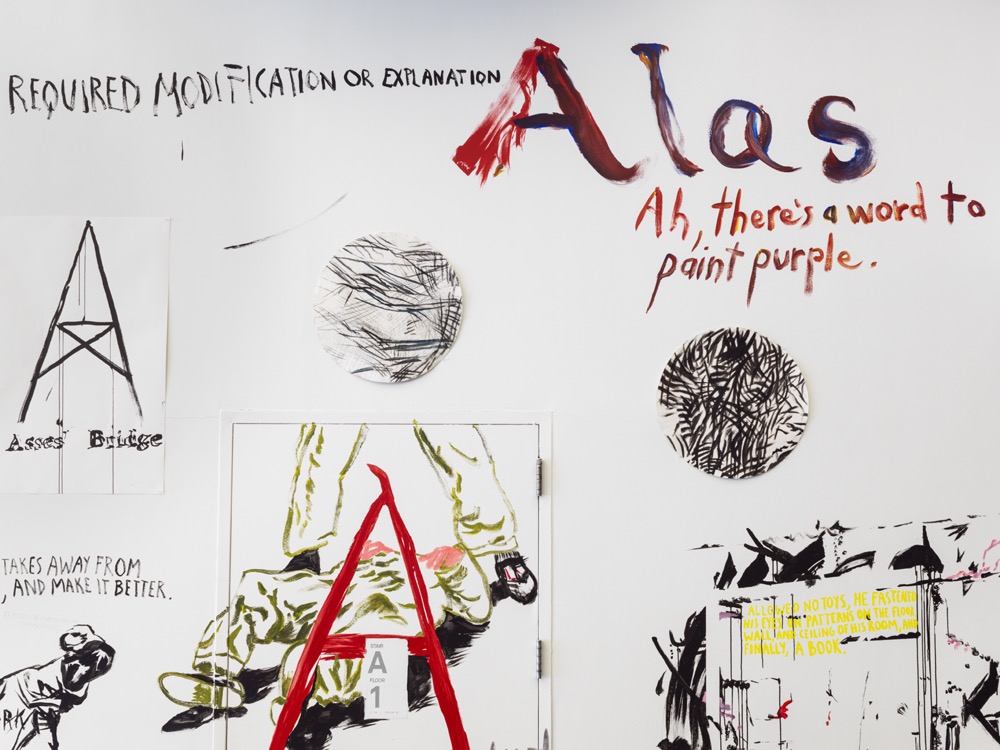

Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work, installation view. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work, The New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through April 9

• • •

A few months ago, I had a coffee with Josh, a good friend from college. Josh didn’t get his first credit card until well into adulthood, and I’m still fascinated by his delight when completing transactions. He swiped his card, the barista flipped the iPad around, Josh added a tip, blithely signed the screen with the words “Hate Reagan,” and pressed enter. “You can do that?!” I asked, incredulous. “It doesn’t matter what you write,” he replied, “as long as you leave some sort of mark.”

I recalled this story while viewing the New Museum’s current Raymond Pettibon retrospective, which borrows its title from Lord Byron (“Mine is a pen of all work; not so new/As it was once, but I would make you shine/Like your own trumpet”). Pettibon’s own hatred of Reagan (a recurring motif in his art) presumably emanates from deep within his formative years—born in 1957, he was the house artist for the doctrinally pissed-off West Coast punk movement of the 1980s, forged in the crucible of Reaganomics. I’d like to think that the man once known as Ray Ginn would have embraced Josh’s quiet, atavistic act of rebellion. Ray Ginn. Reagan. It’s no surprise he changed his name.

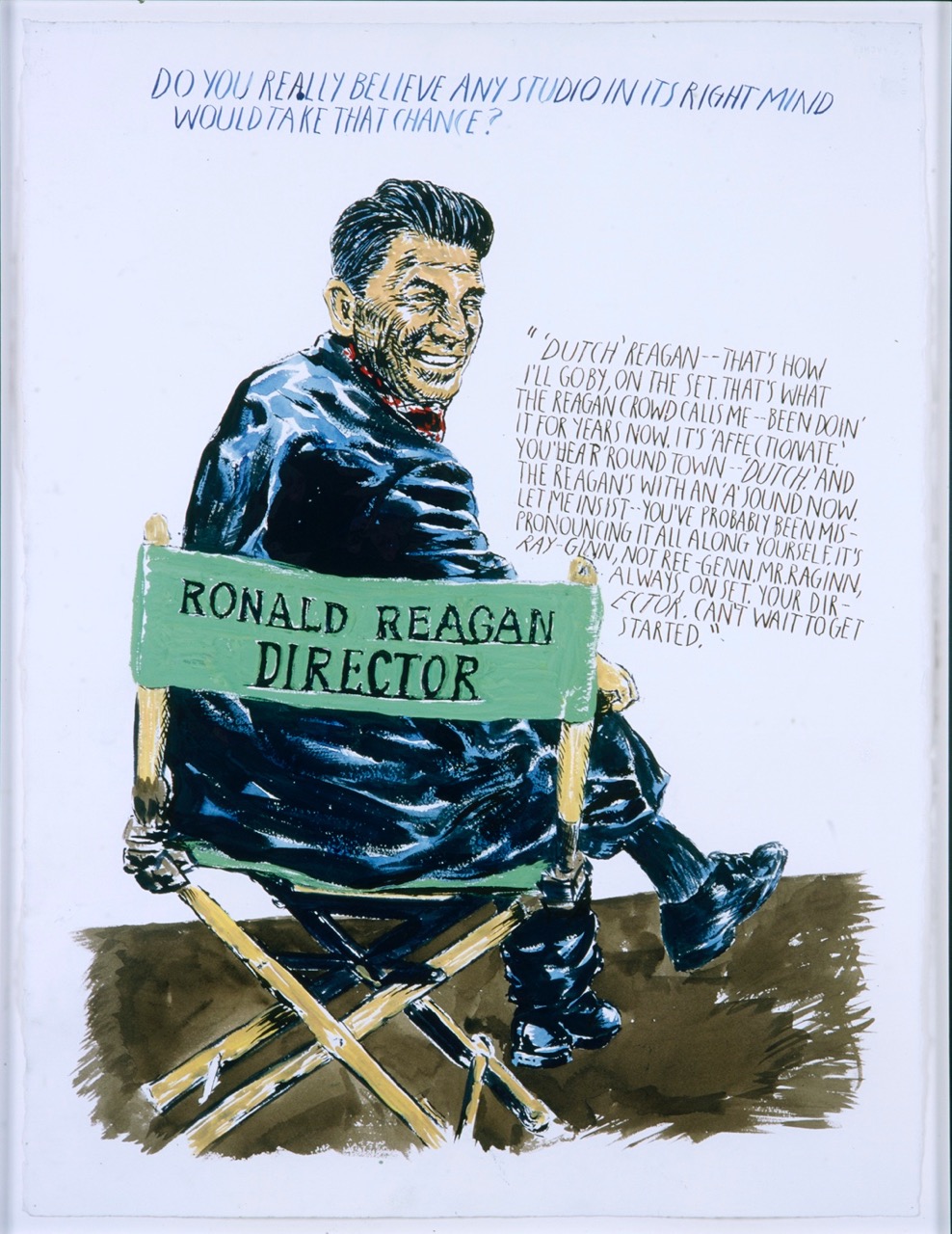

Raymond Pettibon, No Title (Do you really), 2006. Pen and ink on paper, 30 × 22 ½ inches. Image courtesy Sadie Coles HQ.

A Pen of All Work includes many savage sendups of Ronnie, including a pen-and-ink composition entitled No Title (Do you really). This 2006 drawing (Pettibon’s preferred medium) depicts the fortieth president seen from behind as he sits in a canvas director’s chair. Reagan glances at the viewer over his shoulder, and the text scrawled next to him imagines the internal monologue unfolding in the actor-turned-politician’s mind: “. . . YOU’VE PROBABLY BEEN MISPRONOUNCING IT ALL ALONG YOURSELF. IT’S RAY-GINN, NOT REE-GENN. MR. RAGINN, ALWAYS ON SET. YOUR DIRECTOR. CAN’T WAIT TO GET STARTED.” Like Byron’s “recording angel” (quoted above), Pettibon gleefully cedes the stage to his subjects, allowing them to reveal their own foibles and idiosyncrasies through phrases that they may have spoken or that might have been appropriated or written by Pettibon himself. At other times, his drawings’ legends are crafted in a hybrid language lying somewhere between high-flying erudition and low-slung sidewalk philosopher, making it difficult to discern which are literary references and which are sly and knowing epigones.

Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work, installation view. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

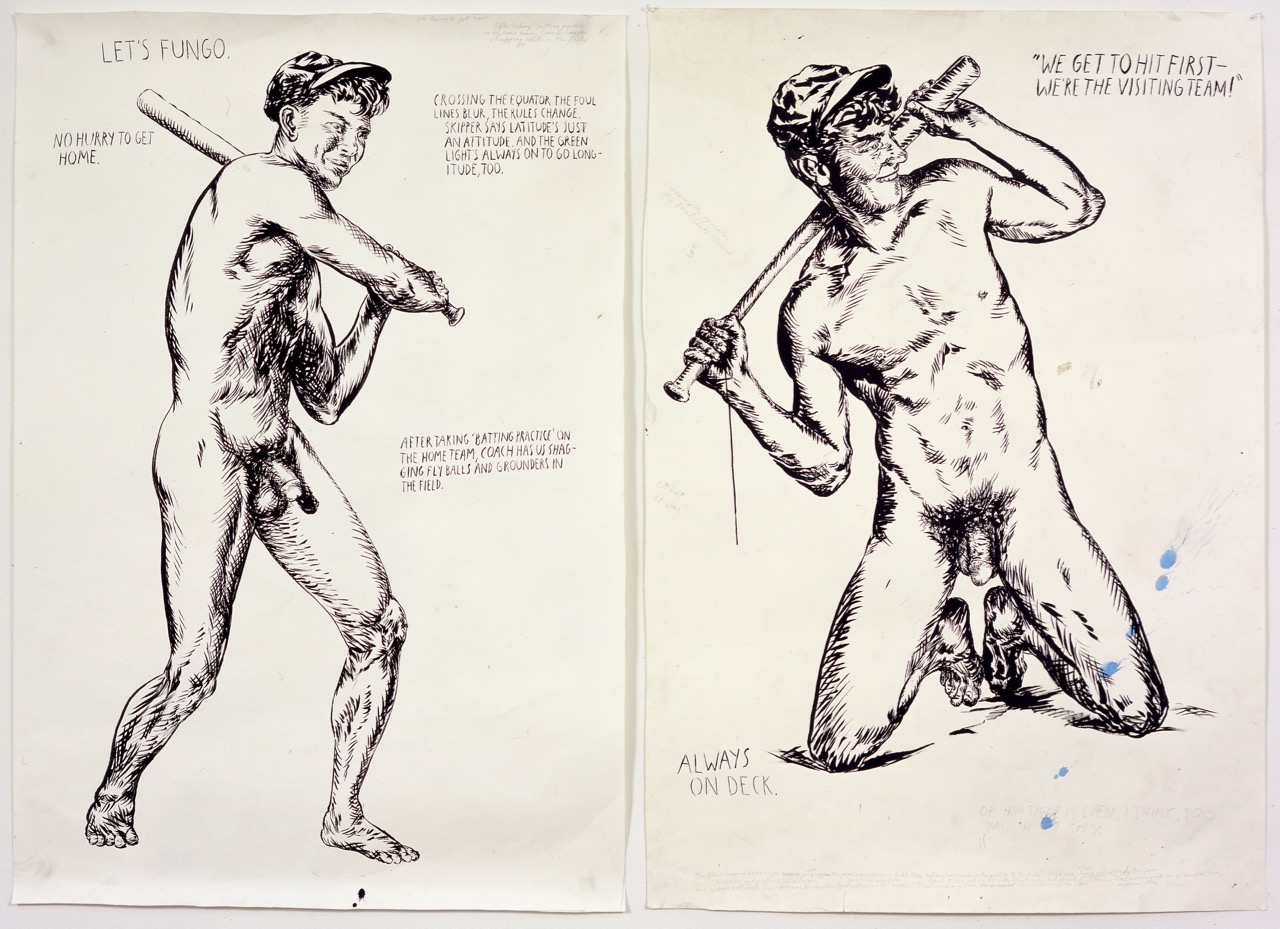

Most of Pettibon’s subjects are drawn from pop culture, from sports, and from the ranks of contemporary politicians. His neat trick is to humanize the monstrous and diminish the heroic. Even sacrosanct superheroes get their comeuppance. No Title (What’s Up Chicken Little?) (1992) depicts Robin, Batman’s diminutive sidekick, suggestively astride an errant tree branch. Holding on for balance, he cannot possibly see the surprise Pettibon has inserted into the scene: a tumescent phallus pointed like a missile toward Dick Grayson’s hindquarters about to enact a painful penetration. A phrase bifurcating the ball sack reads “STILL, HE SEEMED TO BE HAPPY.” Elsewhere, an unnamed yet paradigmatic pair of good old American baseball players feature in the diptych No Title (Let’s Fungo. No) (2003), both totally at ease with their bats and balls fully exposed.

No Title (Let’s Fungo. No), 2003. Pen and ink on paper; diptych, 59 ½ × 41 ½ inches (each).

Clearly, Pettibon has no truck with idolatry, including when it involves placing the artist himself on a pedestal. Accordingly, his most enduring image—the four broken bars that compose the logo of his brother Greg’s seminal band, Black Flag—appears on the four segments of the ground-floor elevator doors one passes through to ascend to the exhibition. Every visitor to the New Museum is compelled to witness his work’s (momentary) demolition. There’s likely also an element of revenge at play: the artist still carps about not receiving residuals from this work for hire. Pettibon’s compositions have always mixed this undercurrent of barely concealed violence with blistering humor, enunciated with a syntactical precision that demonstrates the presence of a first-rate brain.

Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work, installation view. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Few artists can claim the kind of across-the-board appeal that characterizes Pettibon’s reputation. On one hand, his creations provide source material for the estimable art historian Benjamin Buchloh, whose dense catalogue essay is rife with references to Honoré Daumier, Theodor Adorno, and Mikhail Bakhtin. On the other, his woozy street/surfer cred and waggish loyalty to underground culture make him catnip for whatever DIY adherents still fulminate beneath the glossy veneer of the media industrial complex. Given the sheer abundance of his output, there’s almost literally something for everybody. (In addition to the eight-hundred pieces at the New Museum, another five-hundred Pettibons were recently on view in a retrospective at the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg.)

A Pen of All Work differs from what seems to be Pettibon’s preferred mode of exhibiting (seen on ecstatic display at Documenta XI in 2002 and in several solo shows at David Zwirner, among other venues), which involves an in situ installation of drawings and texts inscribed directly on the walls, along with others taped, stapled, and glued. Though the New Museum show takes up three floors plus parts of the lobby, the curators allocate but a single rumpus room in the center of the fourth floor in which to allow Pettibon to wreak havoc. Everywhere else they have carefully, almost tenderly, arranged the drawings thematically for maximum legibility, a decision that permits a measured and refined appreciation of his art, but one that contradicts the anarchic spirit of its production.

In my view, Pettibon’s work is best experienced as a plunge into the querulous and impulsive world of a madman, yet one whose ethical compass is both decorous and salutary, making the rest of us embarrassed at our timid and callow adherence to societal norms. Satire, anger, intelligence, and irreverence all appear in ample measure, so the opportunities are legion for unexpected guffaws and for sharp, shivery shocks of the uncanny. Those who know what a Pettibon installation looks like with fewer refinements may feel constrained by the meticulous wall charts that precisely identify each piece, its provenance, medium, and dimensions.

Still, this survey provides an opportunity to spend an hour or three in the artist’s enviably fertile imagination. Each corner turned uncovers yet another deep dive, as if new drawings are being produced just moments before one encounters them. A motto of sorts appears over a doorway: a single sheet of paper on which the artist has written “TRY EVERYTHING/DO EVERYTHING/RENDER EVERYTHING.” Following that spirit of magnanimity, perhaps the next time you’re prompted to sign an iPad cash register, think of Raymond and of Josh, and leave your mark.

Noah Chasin writes on the intersection of human rights and the built environment in the age of twenty-first-century urbanization. He teaches at Columbia University, where he is affiliated faculty at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights, and at the New School. He is executive editor at the Drawing Center.