Jace Clayton

Jace Clayton

A life, in millimeters: an exhibition details the bland, brutal violence of administration—and renders art complicit.

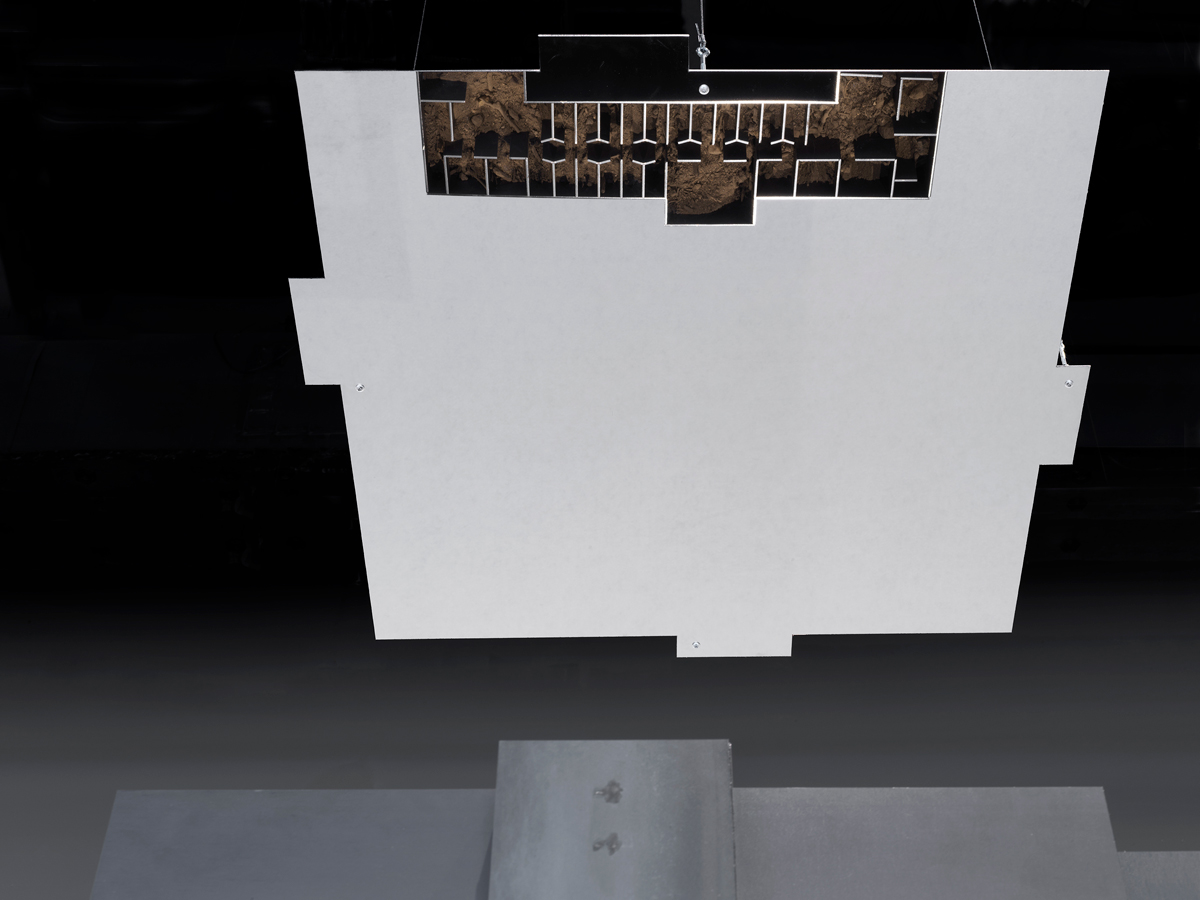

Sung Tieu: Civic Floor, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Sung Tieu: Civic Floor, organized by Natalie Bell, Hayden Gallery, MIT List Visual Arts Center, 20 Ames Street, Building E15, Cambridge, Massachusetts, through July 16, 2023

• • •

Bureaucracy makes the intimate appear distant. It shuns narrative in favor of sorting and compels people to shape stories about themselves to fit its form. This fact propels some great literature, such as Mikhail Shishkin’s polyvocal novel Maidenhair, in which the officious violence of Swiss border policy turns asylum-seekers into Scheherazades. But how to tell a story about bureaucracy? In Civic Floor, an exhibition on view at MIT List Visual Arts Center, Sung Tieu uses sculpture, reliefs, sound, and architectural interventions to sharpen the point of this question.

Four foreboding sculptures occupy the center of the room. Each is a differently shaped, tall, rectilinear volume built from thin sheets of black steel, whose angular walls demarcate what may initially appear to be hollow interiors. The boxy enclosures sit on tables made of the same material. These are the only dark objects in an aggressively bright space (carpeting, walls, artwork on walls—all white), and they draw us in. You can feel a sepulchral gravity even if you don’t yet know that they are named after common prison architectural designs: Galleried, Detail (2022); New Generation, Detail (2022); etc.

Sung Tieu: Civic Floor, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Courtyard, Detail, 2022.

The objects possess a stolid autonomy, but by qualifying every one as a Detail of something larger, Tieu suggests that we consider these artworks as elements networked into a much wider whole—a specific architecture of detention, if not the entire American carceral bureaucracy. Abolitionist geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us that we too are details in this sense: “The prison-industrial complex consists of the uniformed and civilian personnel who work anywhere from the streets to the courts, to the jails, to the prisons, to the postprison-release programs, and so forth. . . . It includes the intellectuals, including myself, who make their living either designing or condemning the design of systems of punishment.”

Sung Tieu: Civic Floor, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Courtyard, Detail, 2022 (detail).

The sculptures stand nearly five feet high; they’re purposely difficult to access. Taller visitors may be able to peer over their sides to discover the forms are partially filled with dirt. Everyone else can glimpse this by looking up into the reflective surfaces of the flat stainless-steel sheets suspended over the sculptures, each one cut to have the same silhouette as the volume beneath it, and allowing a fragmented aerial view. The metal mirror playfully inserts distance and disorientation into the experience of these works. It’s a surprising feature that activates the viewer, whether they’re twisting around to peek inside or working angles for the best selfie.

Sung Tieu: Civic Floor, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Stainless-steel stools are hinged to the walls on either edge of an enormous window overlooking a manicured campus lawn. These ridiculously inhospitable chairs reappear throughout Tieu’s shows, performing double duty as actual gallery seating and avatar of institutional hostility. Nobody wants to hang out in a room where the furniture’s bolted to the floor. Tieu’s Brutalist stools are particularly effective here because they can pass for standard seating inside this concrete and aluminum-clad I. M. Pei building.

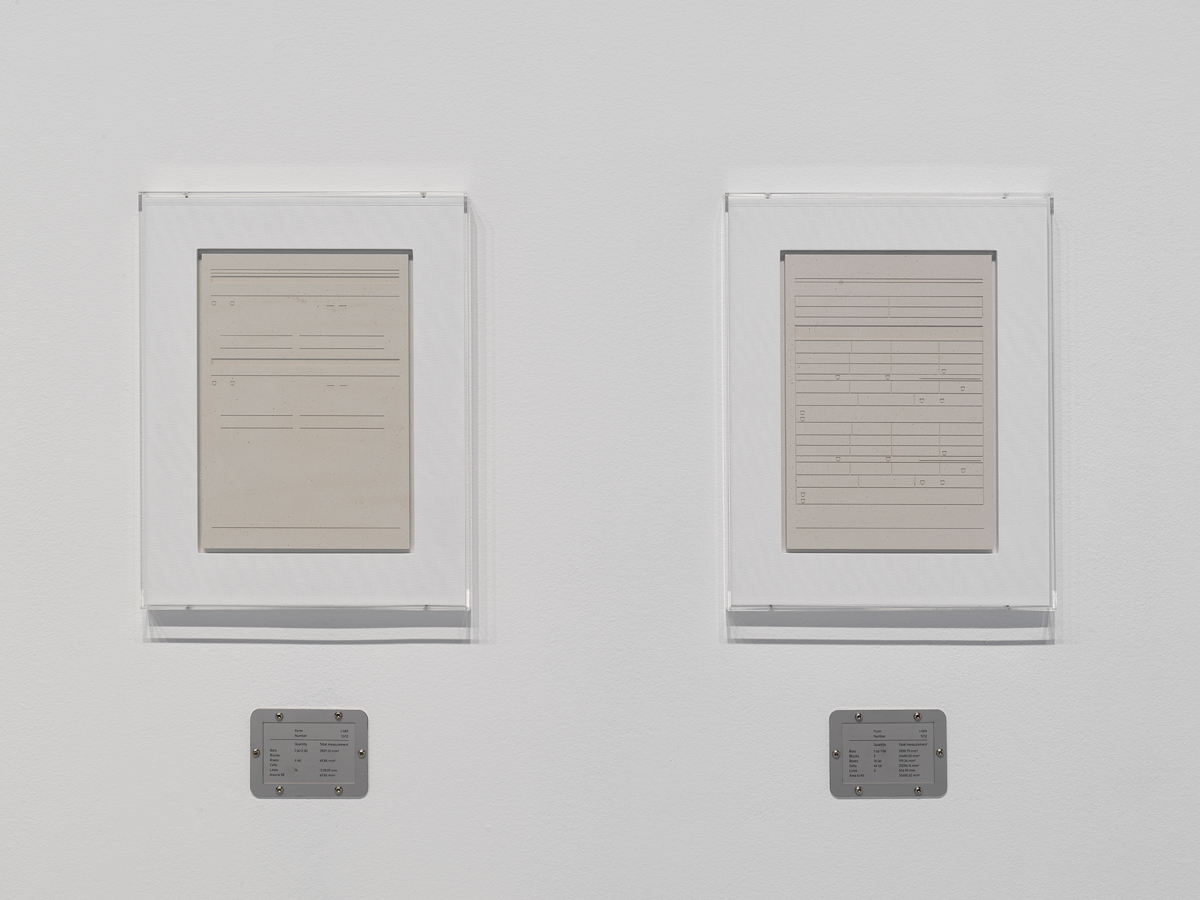

Sung Tieu: Civic Floor, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni. Pictured: Grid, Form I-589, 2022 (detail, above); Numeric Analysis, Form I-589, 2022 (detail, below).

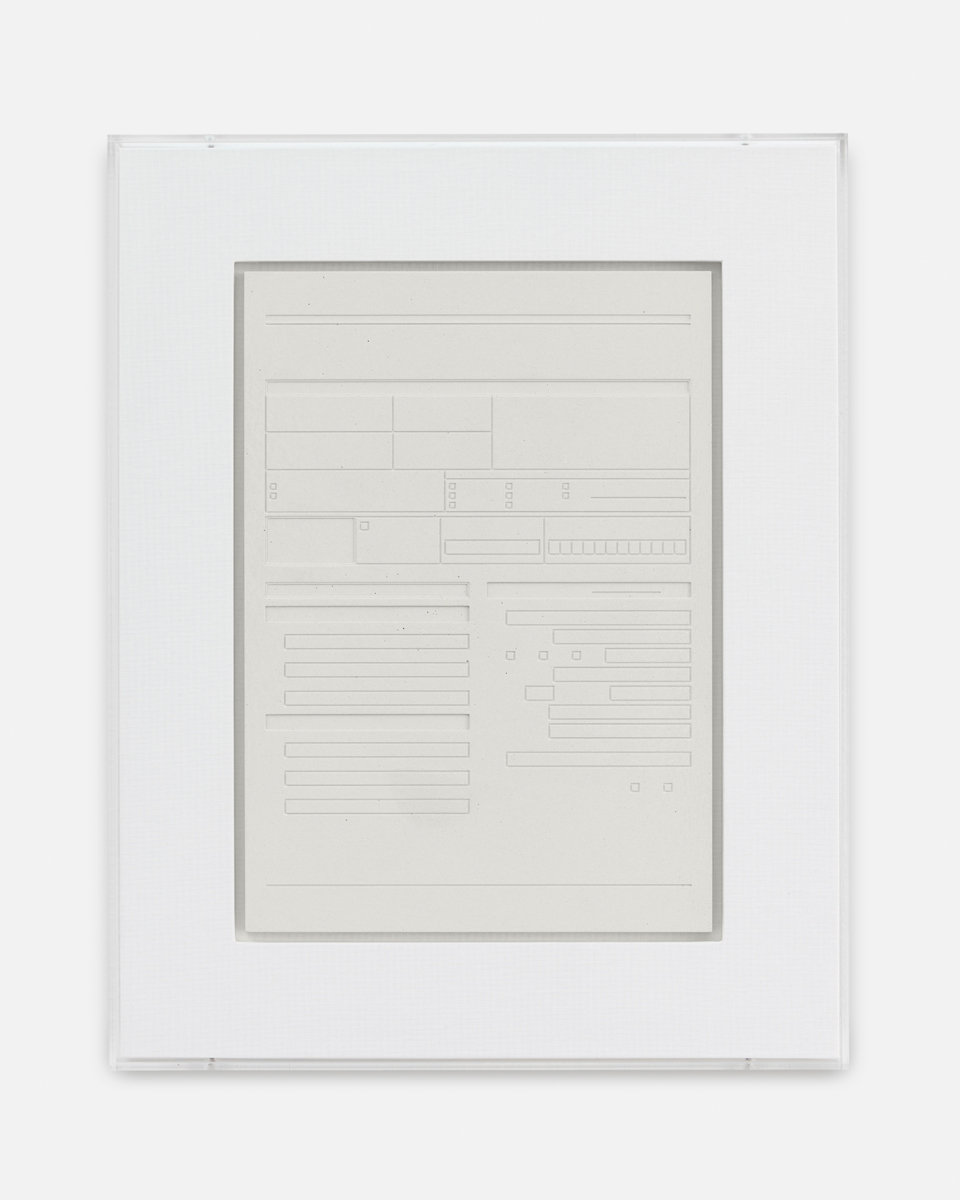

A few dozen ivory-colored plaster reliefs hang on the walls. Every item in this Grid, Form (2022) series is the size of a sheet of paper, punctuated by empty, recessed rectangles of varying heights and widths. The geometric shapes parallel the visual layout of various US government asylum forms. Clear acrylic boxes cover the reliefs, emphasizing the plaster’s fragility. The twelve reliefs that make up Grid, Form I-589 correspond to the Application for Asylum and for Withholding of Removal; the ten constituting Grid, Form I-602 to the Application by Refugee for Waiver of Inadmissibility Grounds; and the fifteen pieces of Grid, Form I-881 to the Application for Suspension of Deportation or Special Rule Cancellation of Removal.

Sung Tieu, Numeric Analysis, Form I-589, 2022 (detail). Laser-engraved stainless-steel plates, screws, 4 3/4 × 3 1/2 × 3/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Mudam. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

A stainless-steel plaque affixed below each Grid, Form reveals a dizzyingly bureaucratic regime of measurement: Tieu has calculated (in square millimeters, down to two decimal places) how much space Bars, Blocks, Boxes, Cells, Lines, and Areas to fill take up on the application in question. The findings are then listed on the plaque, in a laser-etched Helvetica typeface: Blocks Quantity 2 Total measurement 34666.01 mm2. Mind-numbing data accumulates across archival-quality materials. Permanence collapses into mundanity. These reliefs and plates use the logic powering the implacably bland violence of refugee paperwork to reproduce that same violence, measuring the immensity of a life down into minimally differentiated blocks footnoted by junk numbers.

Sung Tieu: Civic Floor, installation view. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Dario Lasagni.

Before we even enter the gallery space, sounds reach out to condition us. Brooding ambience pipes out of eight speakers nestled throughout the gallery’s black open-panel ceiling. Periodically, the beatless audio morphs into sentimental snatches of melody to create an overall effect of heavy Muzak. Much use of the sonic in contemporary art focuses on one of two extremes: sound as forensic evidence (as in Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s considerations of the “earwitness”) or sound-as-sound (“the sonority rather than the message,” in Jean-Luc Nancy’s formulation). Tieu tends toward something in-between, sound as dread transmission, vibes that permeate any container’s solidity.

The acoustics are helped by the wall-to-wall carpeting, which absorbs reflecting waves to yield a warmer, more detailed sound. At the gallery’s entrance, a sign reads:

This exhibition has white carpeting to create a space for visitors to slow down and better engage with their senses. We invite you to remove your shoes or use protective covering.

In other words: please don’t stain the white carpet. The civic is always bounded by a sense of order and cleanliness. Civic Floor is pristine. The dirt is in the Details. Racial whiteness operates as political neutrality, and this is what forms the uneven ground upon which civic rights are built.

Sung Tieu, Grid, Form I-602, 2022 (detail). Plaster, framed in linen on wood and Perspex, ten parts: 17 3/8 × 13 3/4 × 5/8 inches each. Courtesy the artist and Mudam. Photo: Mareike Tocha.

Sung Tieu’s forms startle then engulf the terms by which Minimalists understood their world. Not just key figures like Donald Judd (“A form can be used only in so many ways. The rectangular plane is given a life span.”) or Robert Morris (“Unitary forms do not reduce relationships. They order them.”) but anyone claiming that art objects can exist here-before-us and whole, pointing toward nothing other than what they are. In his landmark 1967 essay on such artists’ forms, Michael Fried said they’re defined by “a kind of stage presence . . . Something is said to have presence when it demands that the beholder take it into account . . . the beholder knows himself to stand in an indeterminate, open-ended—and unexacting—relation as subject to the impassive object on the wall or floor.” Tieu’s work speaks this language of Minimalism with an elegant, chilly precision, at the same time as it centers all that presence is not: withholding, removal, inadmissibility, suspension, cancellation, ellipsis.

Tieu has simultaneous debut solo shows in the US right now, Civic Floor and Infra-Specter at Amant in Brooklyn, which is just as impressive. This is an artist whose ideal medium might be the exhibition itself. Compelling on their own, when staged in a gallery the works intertwine with other systems of power, and the kicker is the way in which aesthetic strategies provide the connective tissue. The show is not thematically “about” the American prison-industrial complex as it abuts national identity policing—it constitutes a detail of it. Civic Floor appears to acknowledge that political awareness starts by recognizing complicity. And that complicity must exist in the making as well. You can say Sung Tieu has elevated bureaucracy into an art form and, necessarily, vice versa. Civic Floor is impeccably installed, exhaustively researched, deeply satisfying, and clearly required a shitload of paperwork, emails, meetings, phone calls, measurements, negotiations, contracts, agreements, cross-references, drafts, revisions, renderings, and forms upon forms upon forms.

Jace Clayton is an artist and writer based in New York, also known for his work as DJ /rupture. His solo show They Are Part is on view at the MassArt Art Museum through July 2023. Clayton is the author of Uproot: Travels in 21st Century Music and Digital Culture (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and is Director of Graduate Studies at the Bard MFA.