4 Columns

4 Columns

4Columns returns with a new issue on September 3. This week we present our third summer missive: the triumphs—and failures—of the tumultuous 1970s in (mostly) nonfiction cinema.

Gay USA. Courtesy Frameline.

Protean, painstaking, and involving multitudes, seismic political shifts are difficult to adequately depict on film, no matter how inherently dramatic. But some of the best filmed chronicles of the 1970s, by focusing on a single event or cohort, help us make sense of that roiling decade—when the various liberationist struggles begun in the 1960s, such as Black Power, the antiwar movement, second-wave feminism, and LGBTQ rights, either effloresced or withered or both.

Germaine Greer and Norman Mailer in Town Bloody Hall. Courtesy Criterion Collection.

Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker’s documentary Town Bloody Hall captures the riotous “Dialogue on Women’s Liberation,” held in Manhattan April 30, 1971. This symposium finds tetchy, twitchy Norman Mailer squabbling not only with the four panelists—“a diverse group of white women,” in the words of Johanna Fateman, each with varying positions, from radical to antipathetic, within or toward feminism—but also with members of the literati-glutted audience. “We witness a debate on a topic as big as the world in Town Bloody Hall, one with no fixed terms or single proposition,” Fateman writes. Though the evening was punctuated by chaotic moments, like discussant Jill Johnston’s making out with two women onstage, “the documentary is not ultimately defined by its hallucinatory, camp qualities,” she continues. “Culturally and legislatively, the women’s movement was on the verge of significant wins, and perhaps Hegedus’s feminist investment in the moment—and this goldmine of material—grounds the work in seriousness.”

Milestones. Courtesy Icarus Films.

Robert Kramer and John Douglas’s Milestones (1975), an amalgam of fiction and nonfiction, plays in a much more doleful register. Begun just after US participation in the Vietnam War had ended, the film “expansively charts the affective landscape of a radical tranche of the generation that came of age with the conflict,” Erika Balsom observes. “From May to October 1973, Kramer and Douglas wandered from Vermont to Utah, filming friends on 16mm in loose relation to a script.” Most of these comrades, like the filmmakers themselves, are “white, middle-class nonconformists who had been involved in the Movement in the late 1960s, only to be now left wondering how to live after a sense of disappointment and isolation has set in,” Balsom writes. “Reconciling themselves to the realization that revolution isn’t just around the corner, they reckon with personal dilemmas and attempt to rearticulate their commitments. Milestones is a desultory portrait of this milieu and its malaise, tracing a mounting feeling of disconnection from organized struggles against oppression and a concomitant retreat into private life.”

Gay USA. Courtesy Frameline.

Other films from this period reveal the thrill of publicly celebrating that which too often had to be kept private. Arthur J. Bressan Jr.’s Gay USA (1977), assembled from Pride parades on June 26, 1977, in different US cities, is a dynamic portrait of the modern LGBTQ movement, then not quite a decade old and four years away from the devastations of the AIDS pandemic. “This dense, exhilarating collage . . . reflects the liberationist fervor of the ’70s, utopian hopes not yet extinguished. Or, at the very least, not yet co-opted and marketed: no ghastly rainbow-hued merchandise, no corporate slogans soil these festivities,” film editor Melissa Anderson notes.

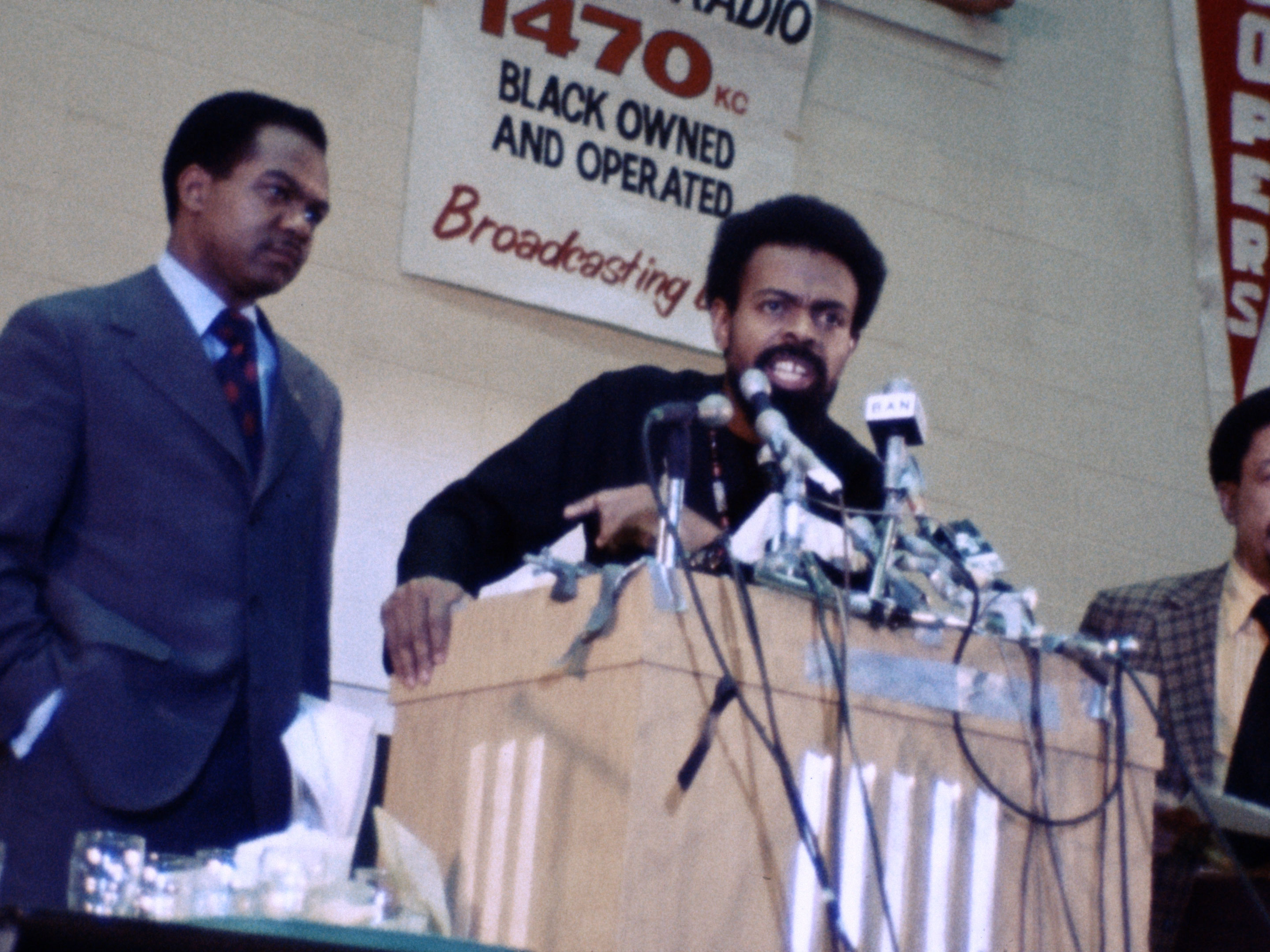

Amiri Baraka in Nationtime. Courtesy Kino Lorber.

Some ’70s documentaries focus on ideals forged from widely disparate factions. William Greaves’s Nationtime, a record of the National Black Political Convention held in Gary, Indiana, the weekend of March 10–12, 1972, highlights the director’s “gifts for capturing the ways that energy shifts and ricochets among groups of people,” Anderson observes. Cheers are drowned out by dissent at an event that “brought together nearly ten thousand African Americans across the political spectrum—from Republicans to socialists to Black nationalists, from elected officials to Black separatists—to develop an ambitious agenda for all Black Americans.” Much of that agenda, Anderson continues, “remains far from reach,” having called for, among other demands, “the elimination of capital punishment, statehood for the District of Columbia, the establishment of national health care, and a guaranteed annual income.” Yet the fact that at least some of those action items are now being seriously contemplated by the highest office in the country proves that a gathering from nearly half a century ago still reverberates.