David Cote

David Cote

A single Coen Brother takes on double the toil and trouble.

Denzel Washington as Macbeth and Frances McDormand as Lady Macbeth in The Tragedy of Macbeth. Courtesy Apple TV+.

The Tragedy of Macbeth, written and directed by Joel Coen, now playing in select theaters and available on Apple TV+

• • •

Seems you can take a Joel out of the Brothers, but you can’t take the Brothers out of Joel. For The Tragedy of Macbeth, writer-director Joel Coen went solo, “untimely ripp’d” from his filmmaking symbiote Ethan. But don’t expect this splendid art-house curio to deviate too much from the duo’s four-decade mulching of noir, farce, and myth, and their whiz-bang camerawork. Notwithstanding the Jacobean verse and theater-y studio sets (not to mention a leading man of color), Macbeth is as undilutedly Coenic as they come: a crime caper that spirals out of control to crush evildoers, justice ambivalently served in an amoral universe.

Stark, monumental, and legitimately scary, Coen’s grisly grisaille caps an unofficial trilogy of black-and-white auteur Macbeths, alongside Orson Welles’s flawed but kicking 1948 capture and Throne of Blood, Akira Kurosawa’s impeccable samurai translation from 1957. Shakespeare on film has a long and bumpy history, with trouble often arising when trying to navigate the aural needs of the poetry and the visual needs of film. Kurosawa and the Russian Grigory Kozintsev (who directed epic, elemental screen versions of Hamlet in 1964 and King Lear in 1971) were able to sidestep the language, to some extent, but never underestimate the twofold thrill that well-edited, well-delivered Shakespeare combined with cinematic assurance can produce. Not since Roman Polanski’s blackhearted, carnal adaptation from 1971 has a film of the Scottish Play stared so deeply and rapturously into the ruins of human ambition. Coen does it with fidelity to the Folio, shrewd casting, and a few strategic interpretative landmines.

He opens with a worm’s-eye view of a murder of crows (three, to be precise) circling ominously against a blank sky—one of those round or rolling icons the Coens love to open with (a windblown fedora, a tumbleweed, a rotating barbershop pole), symbols of life’s inexorable, restless circularity. Also, as any good lit student will tell you, birds are a key motif in Macbeth; more than a dozen avian species are namechecked in the script, croaking, shrieking, haunting, swooping. The crows’ wheeling pattern recurs throughout the film: a letter lit on fire is thrown to flutter in the wind; a crown, struck from the title villain’s head, spins heavenward.

Kathryn Hunter as Witches in The Tragedy of Macbeth. Courtesy Apple TV+.

By the explosive final moments of Macbeth, those three crows will have multiplied shockingly, a visual pun suggesting that the “murder” we’ve witnessed in the foregoing 105 minutes is nothing compared with what’s to come. In this monochromatic nightmare zone, form is fluid and the senses susceptible to outside influence: nothing is what it seems. The crows resolve themselves into the three weird sisters—represented by the contortionist hell-pixie Kathryn Hunter. The famously hallucinated dagger before the murder of King Duncan turns out to be a homely architectural feature. Drops of blood from a corpse’s hand hit the floor like cannonballs. And of course, the Macbeths, played as two childless, late-middle-aged strivers by the never-better Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, hide their lust for power under courtly politesse. Damned and double indemnified, they’re the most ruthless spouses in Shakespeare’s noirest of tragedies.

Not for nothing has Shakespeare’s 415-year-old play been moviemaker catnip: it’s a fever dream of blood, ghosts, witches, a walking forest, a phantom shiv, and gore-drenched visions afflicting the guilty. Shakespeare does not specify a fog machine in the stage directions, but the tale is practically meaningless without yards of the fluffy white stuff.

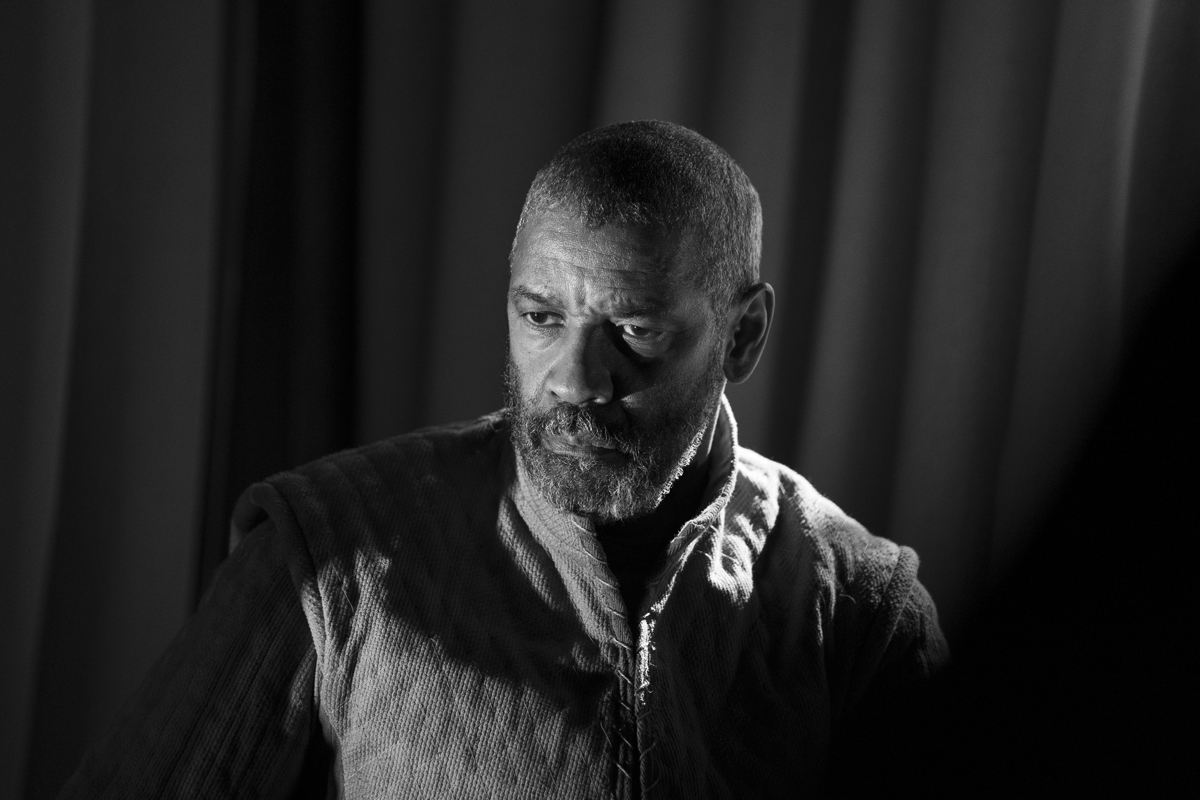

Denzel Washington as Macbeth in The Tragedy of Macbeth. Courtesy Apple TV+.

Unsurprisingly, Coen has studied his predecessors and borrowed freely. After Welles (by way of Fritz Lang), he adopts a fiercely geometric, Expressionist theatricality that roves through Gothic-Brutalist architecture (Stefan Dechant’s production design alternately dwarfs and cloisters the actors). Like Polanski, he beefs up the relatively minor character of Ross (Alex Hassell, sleek as an otter) into a sinister double-dealer who serves both the tyrant Macbeth and his righteous enemies. Unlike Welles and Polanski, Coen doesn’t relegate the blood-chilling soliloquies to voiceover, but lets Washington deliver them in scene, braving any fear of staginess.

That term “stagey” tends to be pejorative in movie discourse, but there’s a beauty in some films that embrace the tape marks and dolly tracks, as it were. Coen’s canny blend of computer effects and long, choreographed takes keeps us tensely immersed in a fairytale realm that has the materiality of a stage set but one filtered through an insomniac’s delirium. The camera likes to follow Washington in his great, gruesome monologues, prowling a shadow-slashed arcade or descending a steep staircase. McDormand illustrates how Lady M’s sleepwalking scene is a showcase for spectacular acting that’s allowed to breathe; the actress lets out a howl of grief as the guilty scrubbing of imaginary blood from her hands melts into the cradling of a phantom (stillborn?) infant.

Frances McDormand as Lady Macbeth in The Tragedy of Macbeth. Courtesy Apple TV+.

Both leads approach Shakespeare’s language with a focused naturalism that renders the verse dynamic and spontaneous even to seasoned theatergoers. An old-school movie star who always makes the role come to him, Washington creates powerful sensations with an economy of means—a limited but hyper-eloquent vocabulary. A self-mocking frown, a bonhomous chuckle that collapses into a blank stare and dead eyes: he’s the ice-cold jazzman with surgical-strike line delivery. Matching him in focus and tenacity is McDormand, who deteriorates beautifully from bullheaded hausfrau to white-haired wraith.

Corey Hawkins as Macduff in The Tragedy of Macbeth. Courtesy Apple TV+.

The ensemble is peppered with choice cameos: Stephen Root as the boozy, chatty Porter (a dribble of low-key comic relief); Bertie Carvel, all thornbush eyebrows and sardonic smirk as the battle-hardened, doomed Banquo; Corey Hawkins’s Macduff as the anti-Macbeth (loyal, honest, with children); and the previously noted Hunter as the weird sisters, croaking her lines like a raven and squatting high on rafters like a bird of prey. Hunter, a petite, triple-jointed stage veteran, is the trickster imp of the film, its muse and succubus, a morphing oracle whose witchy equivocations are mirrored in her unstable form.

If the magic realm is always in flux, Macbeth’s human sphere is brutally fixed and directional. Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel constantly frames scenes in narrow corridors, sequestered courtyards, or country roads hedged by trees. The decisive swordfight between Macduff and Macbeth takes place on a walled bridge leading to a tower. All this pinched, confined architecture evokes a sense of claustrophobia and suggests that the characters are trapped on blind conveyor belts channeling them to their fate, beasts in a slaughterhouse. Had Coen the nerve to retitle the film as he wished, would he have alighted on Blood, Simply?

David Cote is a theater critic, playwright, and librettist based in Manhattan. He reviews theater for Observer. His work has been produced in New York, Cincinnati, Chicago, and London.