Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Five poetic stories in image and text reveal the ever-present power of nature, greed, friendship, and philosophical inquiry.

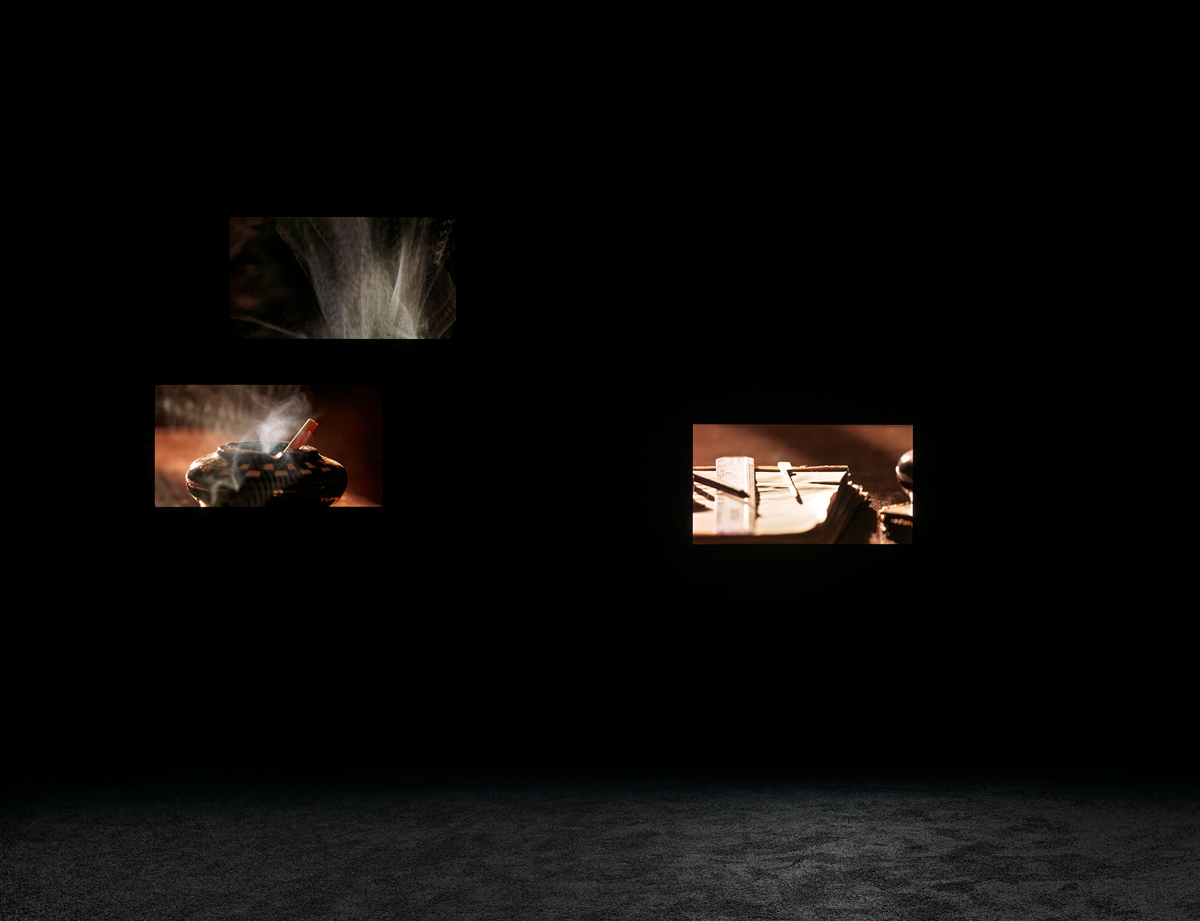

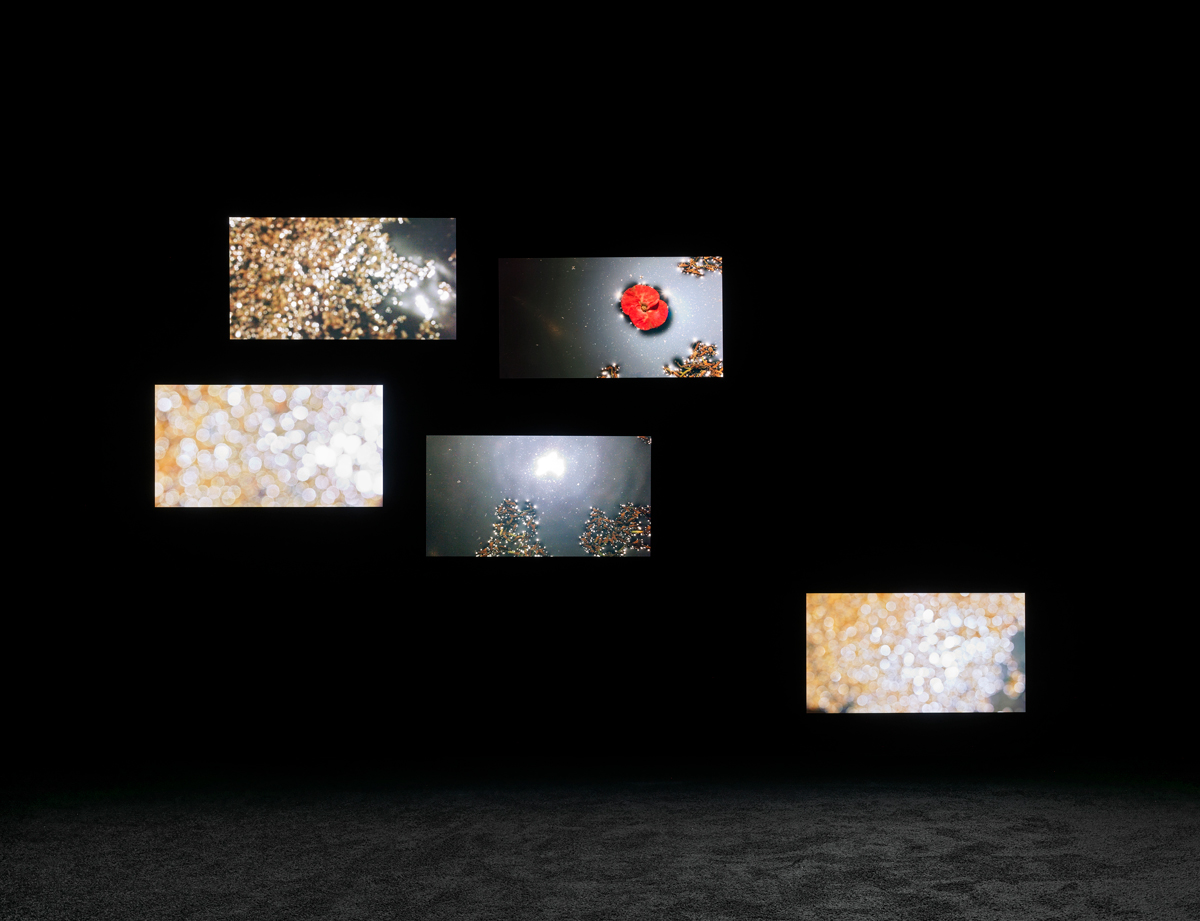

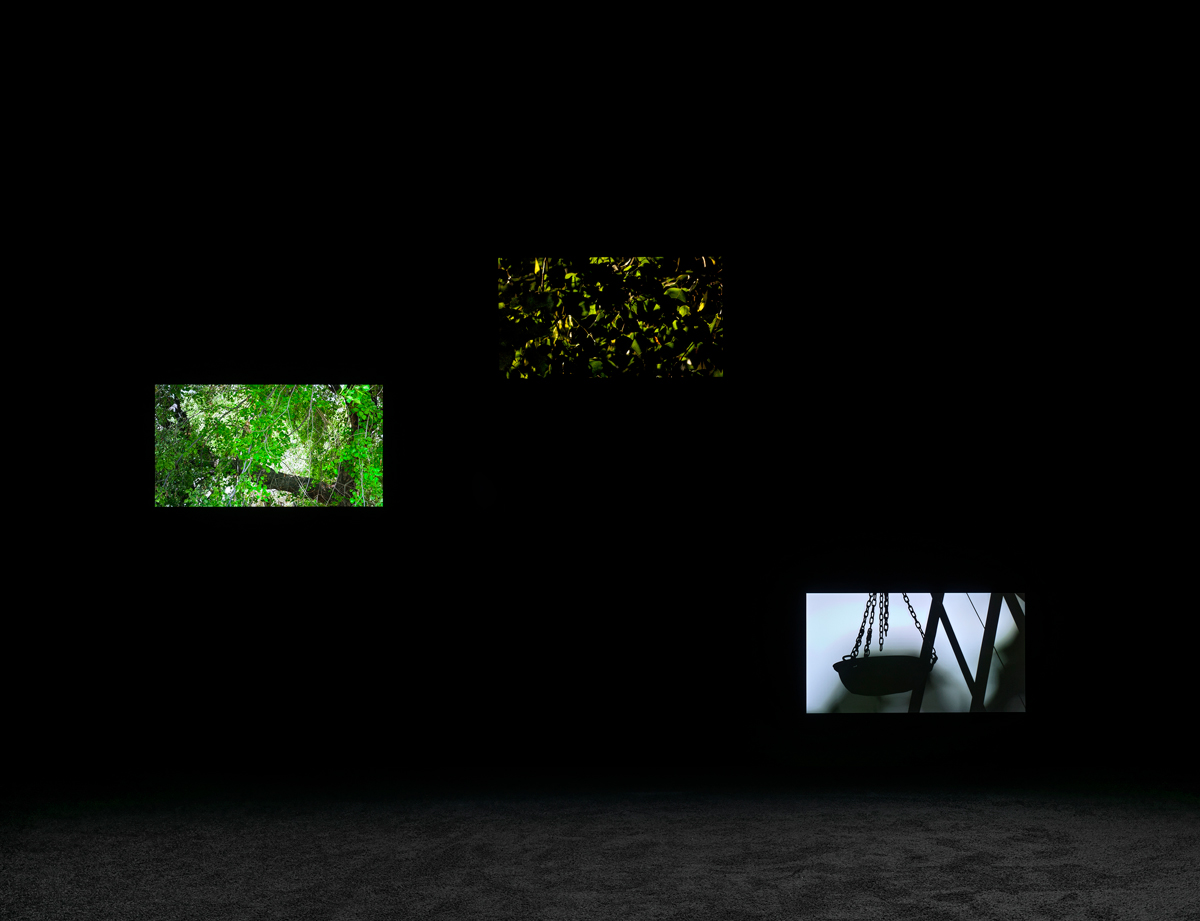

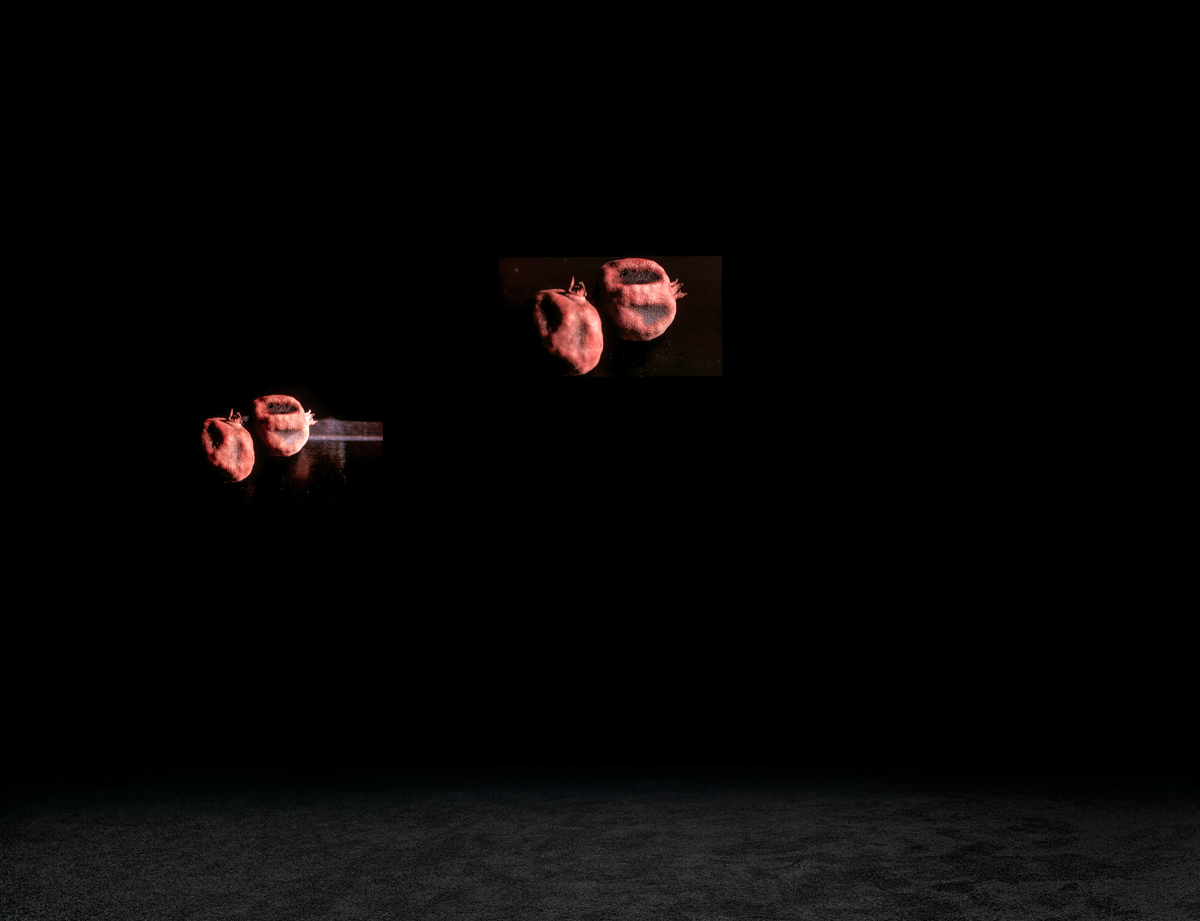

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. Pictured: The Peacock’s Graveyard, 2023 (still). Digital video installation, seven screens, dimensions variable, 28 minutes 16 seconds.

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, Marian Goodman Gallery,

24 West Fifty-Seventh Street, New York City, through February 24, 2024

• • •

I bumped into Amar Kanwar when I went to Marian Goodman to see The Peacock’s Graveyard. Commissioned in 2023 for the fifteenth Sharjah Biennial, his twenty-eight-minute, seven-channel video installation is being shown for the first time in the US. Kanwar is known for an approach to documentary that engages social and political issues, often those rooted in events in South Asia but with a much larger, global import—sexual violence, borders, censorship and freedom of speech, environmental devastation—and always through a lens of poetic storytelling. This new work differs from earlier projects: it’s sparer, almost haiku-like in its visual and textual forms. “With so much happening in the world, it seemed to be a good idea to start from the beginning, to go back to basics,” he told me.

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. Pictured: The Peacock’s Graveyard, 2023 (still). Digital video installation, seven screens, dimensions variable, 28 minutes 16 seconds.

The result is less an origin story than a lyrical mapping of our current state of affairs—though a fragmented, collaged one. Rather than tracing a single, if elusive, narrative, as many of his past film-based projects have, The Peacock’s Graveyard is organized around a series of episodes named for their protagonists: The Priest, The Hangman, The Landlord, The President, and Pabu Holla (a pair of friends). Written by the artist, the stories are adapted from ancient Indian folklore and more modern parables, some imagined or reimagined, and distilled into short stanzas. The text is projected on the wall of an inky black room, synchronized with images that appear and disappear elsewhere on the wall at a studied pace. Other than some archival footage drawn from old Indian movies at the beginning—of a ship on stormy seas and torrential rains, fitting symbols for the world we find ourselves in now—Kanwar shot everything else: nonhuman entities (with one or two exceptions), including flora, fauna, the natural elements, the sky and the earth, an ashtray, and so on.

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. Pictured: The Peacock’s Graveyard, 2023 (still). Digital video installation, seven screens, dimensions variable, 28 minutes 16 seconds.

In The Priest, images of water—a scummy pond, sometimes with a poppy floating on the surface, that sparkles like a starry sky—share space with the story of a holy man drinking from a stream. He angrily accuses a youth of muddying his water, to which the young man replies that it cannot be his fault because he is downstream. The priest goes on to blame every one of the young man’s ancestors, the latter protesting their innocence—they are all dead, incapacitated, or somewhere far away. The priest eventually sics his dogs on the young man, who meets a grisly end. As the story unfolds, it’s impossible not to think of the violence enacted over land and resource rights, the instrumentalization of long-dead histories to fuel and justify today’s bloodthirstiness. The Hangman presents leafy branches in varying degrees of close-up to accompany an account of an executioner who proudly practices his skills on a lonely tree until one day a branch breaks and falls on him. The end of the story is abrupt: The hangman lost his mind / He quit his job / and now waits for his pension. This is black comedy at its finest, thanks to the casual alignment of state-sanctioned murder, madness, the protocols of wage labor, and the inefficiencies of the benefits office.

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. Pictured: The Peacock’s Graveyard, 2023 (still). Digital video installation, seven screens, dimensions variable, 28 minutes 16 seconds.

The next story is about capitalist extraction: a greedy landlord charges rent to an old beggar who lives in his worst property. The beggar asks the landlord to bury him with his box in a graveyard guarded by peacocks. The landlord keeps his word, even after discovering the box is filled with treasures. But when he falls into debt, he digs it up to help himself to a gold coin. The finger that touches the coin explodes in pain that can only be cured by tying a bottle of medicine to it for the rest of his life. This is a fairy tale, a fantasy of comeuppance. As the words of this episode appear on part of the wall, images of peacocks strutting in the rain—their feathers the most amazing ultramarine blue, almost otherworldly in their intensity—are juxtaposed with stormy skies. The brilliance of Kanwar’s editing is apparent the moment we read the landlord has taken the coin, and a nearby frame shows the bird turning his head suddenly. In real life, it must have been startled by the sounds of Kanwar’s filming, but in the final cut, its movement reads as one of vigilance and witnessing.

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. Pictured: The Peacock’s Graveyard, 2023 (still). Digital video installation, seven screens, dimensions variable, 28 minutes 16 seconds.

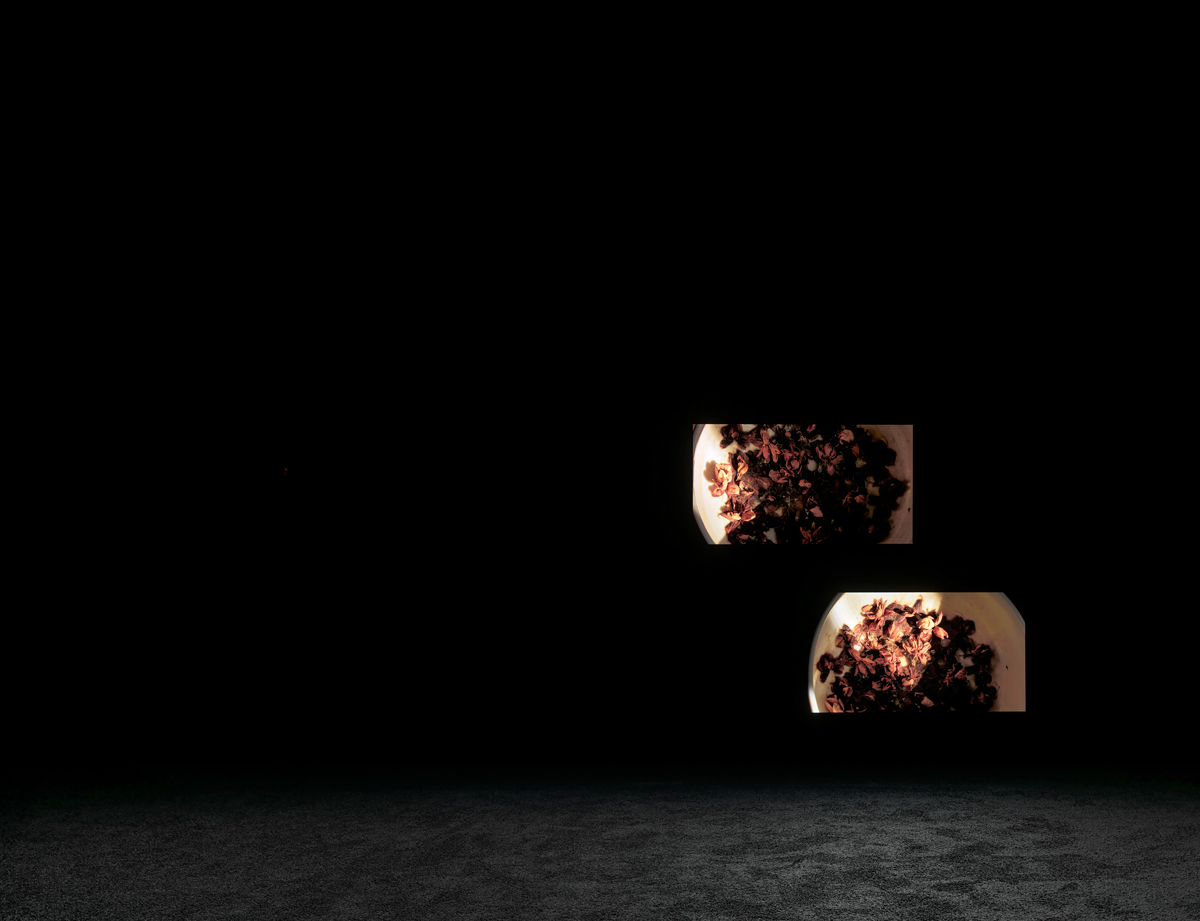

A president asks his speechwriter to write his obituary—since the planets are aligned, it is likely he will die tonight, he says. He does die, but only because the speechwriter murders him. The next day, his obituary is released: The great leader passed away tonight wide awake and in his full senses. It is believed that he will return soon to join his loving followers again in the mortal realm, reincarnated and reborn in his new form as a pomegranate. The images we see—the tools of a writer’s trade arrayed on a desk, smoke rising from a cigarette, blood-red flowers and shriveled, bruised pomegranates—speak to backroom dealings and a degraded political sphere, and (via the actions of the speechwriter) art’s complicity in the worst forms of politics.

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. Pictured: The Peacock’s Graveyard, 2023 (still). Digital video installation, seven screens, dimensions variable, 28 minutes 16 seconds.

And then there’s the story of Pabu and Holla, two friends who meet under a bridge to debate the questions of life: whether birds die or simply soar endlessly in the ether, whether the sun is reborn every night, the nature of dreams and of time. They contradict each other and even speak past each other, their conversation devolving into a series of non sequiturs, disconnected and lacking mutual understanding. But no matter—when assassins come to their village, they are the only survivors, hidden under the bridge and oblivious to what’s happening around them. Pabu and Holla’s philosophizing, even at its most inane and unproductive, is their salvation. Above their story, a moon moves across the sky, our view interrupted by a silhouetted tree trunk, a lovely contrast of the fixed and the cyclical; we don’t see stars, but we see a bowl of star anise in another shot, as if the vastness of the universe has condensed into this tiny, ordinary thing.

Amar Kanwar: The Peacock’s Graveyard, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Alex Yudzon. Pictured: The Peacock’s Graveyard, 2023 (still). Digital video installation, seven screens, dimensions variable, 28 minutes 16 seconds.

Religion, state violence and its agents and bureaucracies, capitalist greed, political power, and arrogance, but also the salvation offered by friendship and philosophy and a close study of the world: The Peacock’s Graveyard speaks to all of these with a complicated temporality. Its parable-like form evokes ancient wisdom, as if the problems that we’re facing are as old as time itself—but when a plane flies through the sky over a canopy of trees, or a politician wants to write an obituary, or a man speaks on a cell phone, we are pulled back into the present. The lesson of these stories, which all speak so clearly to the contemporary, seems not to be that we haven’t learned anything after so many millennia—that we’re just living these same scenarios over and over—or even that the past can guide us in facing the future. Rather, they appear designed to help us understand a now that we aren’t yet able to grasp, a fact Kanwar alludes to in the film’s dedication “to your nausea, amnesia, aphasia and insomnia, your trembling fingers and sliding speech,” a list of what is standing in the way of our clarity. By slowing us down, by offering us knowledge beyond that claimed by reportage or analysis or theorizing, by reminding us of the world’s persistent beauty, Kanwar gives us the gift of being able to see through the present in our search for a peace that is, as he puts it, “mutual, parallel and together.” I can’t think of anything more galvanizing than that.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns, and is author of Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts (Badlands Unlimited, 2018). She is currently working on a new book, Seven Pictures for a New World, and a volume of collected essays.