Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

From Hercule Poirot to the Capitol dome: three artists offer large experimental works.

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

Brand New Heavies, curated by Racquel Chevremont and Mickalene Thomas (Deux Femmes Noires), Pioneer Works, 159 Pioneer Street, Brooklyn, through June 20, 2021

• • •

Brand New Heavies, an exhibition at Pioneer Works organized by artworld power couple Mickalene Thomas and Racquel Chevremont, working under the moniker “Deux Femmes Noires,” is not so much a curatorial statement as a proposition. What if, instead of choosing work that responds to or elaborates a preconceived idea, one simply invites artists who are on the verge of something big to make whatever work they want, giving them the time, space, and resources to take risks and push themselves in new directions? (The experimental approach seems well suited to Pioneer Works, an artist-run cultural center that houses residency studios as well as a variety of technology labs in addition to its 5,500-square-foot exhibition space.) The resulting show, consisting of large-scale installations by Abigail DeVille, Xaviera Simmons, and Rosa-Johan Uddoh, is a pretty convincing argument that the experiment has worked.

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

A video by Uddoh, a young British video and performance artist, is screened in a black box lined with heavy curtains, which seems appropriately theatrical given the subject matter on view. Titled Black Poirot, the video is a witty and (for this mystery fan) even mind-blowing rereading of one of the most famous characters in mystery writing, Agatha Christie’s eccentric Belgian detective, who—in over thirty novels as well as plays and short stories—circulated among the British aristocracy, helping them solve their embarrassing murders, robberies, and scandals. Intertitles rendered in an ornate serif typeface from old paperback editions of the books indicate that Uddoh’s video is structured in the same way as almost every Christie novel: “Poirot Arrives at the Gates of the Manor House,” “The Various Characters Are Introduced,” “Poirot Interviews the Inhabitants,” “Inspector Jap of Scotland Yard Hastily Arrests the Wrong Person,” “ ‘Hastings! We Must Return to the Scene of the Crime,’ ” and so on. But what we see in Uddoh’s revision is far from the old, familiar Hercule.

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

By melding clips from the greatest of all Agatha Christie adaptations—the British series starring David Suchet that ran between 1989 and 2013—with archival photos, video, text, and audio of Black intellectuals and performers including Franz Fanon, Édouard Glissant, Whitney Houston, Saidiya Hartman, and others, Uddoh offers a stunning insight: that in his outsider status as a World War One refugee “flung from the comfort of his homeland into the diaspora,” “the foreigner with nowhere else but our hostile England to call home,” Hercule Poirot was, in fact, Black, in structural if not literal terms. Uddoh then pushes this observation to its logical conclusion. Drawing on Glissant’s thesis that colonial power strips from its oppressed subjects the right to opacity (an inner subjectivity not exposed entirely to the Western gaze), the video’s narration argues that “Black Poirot Reveals the ‘Western epistemological project’ a.k.a the Insistence on Constantly Asking, ‘Why? What? Who? Whodunnit?’ of Every Individual, as a Colonialist Plot.” By allowing Poirot to fully claim his Blackness, he reverses the colonialist gaze, revealing the dirty secrets of whiteness to itself.

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

Both Simmons’s and DeVille’s installations come at the question of political change and freedom, but in ways that are subtle, even oblique. Simmons’s construction, Even in the variations, the division of pleasures help situate us to advocate for, is a structure of refuge for those engaged in struggle. Hundreds of terra-cotta orbs, made onsite by a team of ceramicists, are mounted on a welded frame, turning them into a fifteen-foot-high circular construction. Their unglazed clay surfaces are organic; they also feel strangely corporeal. Walk through the large, irregular opening in the structure and you will see two video monitors hung back to back. On one, text appears and dissipates: “Yesterday, during sunset or as we like to call it, ‘the golden hour,’ we spoke loudly and in great unison when we said ‘don’t buy where you can’t work,’ ” or “We have grown accustomed to this particular landscape and have come to appreciate and care for it even while pushing against it. We keep ourselves set on the gorgeous vision of what it feels like to simply be in any space unencumbered.”

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

This is the language of organizing, the logic of continuing to fight. In the other video, we see a different, but no less urgent, motivation in the search for freedom: the libidinal impulse. Here, blurred images from internet erotica, emphasizing the touch of hands on a body, play out endlessly—a deeply effective move when so many of us are starved for human contact after a year of lockdown. We continue to fight so we can continue to fuck, the piece seems to suggest—those who protest are motivated by both anger at injustice and the pleasures that come from liberation.

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

DeVille’s sculpture The Observatory is a twenty-foot-high steel armature in the shape of the Capitol dome sheathed with chicken wire into which holes have been torn open. It was conceived before the January 6 assault on the Congress by Trump supporters, and while the tattered wire might well suggest a violent attack on democracy, the piece alludes to other, longer histories. Inside the dome, seven screens show a montage of still and moving images: an antique map of lower Manhattan, dating from when the area housed a village of free Black folk; legal writs from the eighteenth century referring to the destruction of the site; and images of the Historic Stagville Plantation in North Carolina, Sullivan Island in South Carolina—where more than forty percent of the over 400,000 enslaved Africans brought to Colonial America arrived—and the Combahee River (where Harriet Tubman led a raid in 1863, successfully liberating over 750 people).

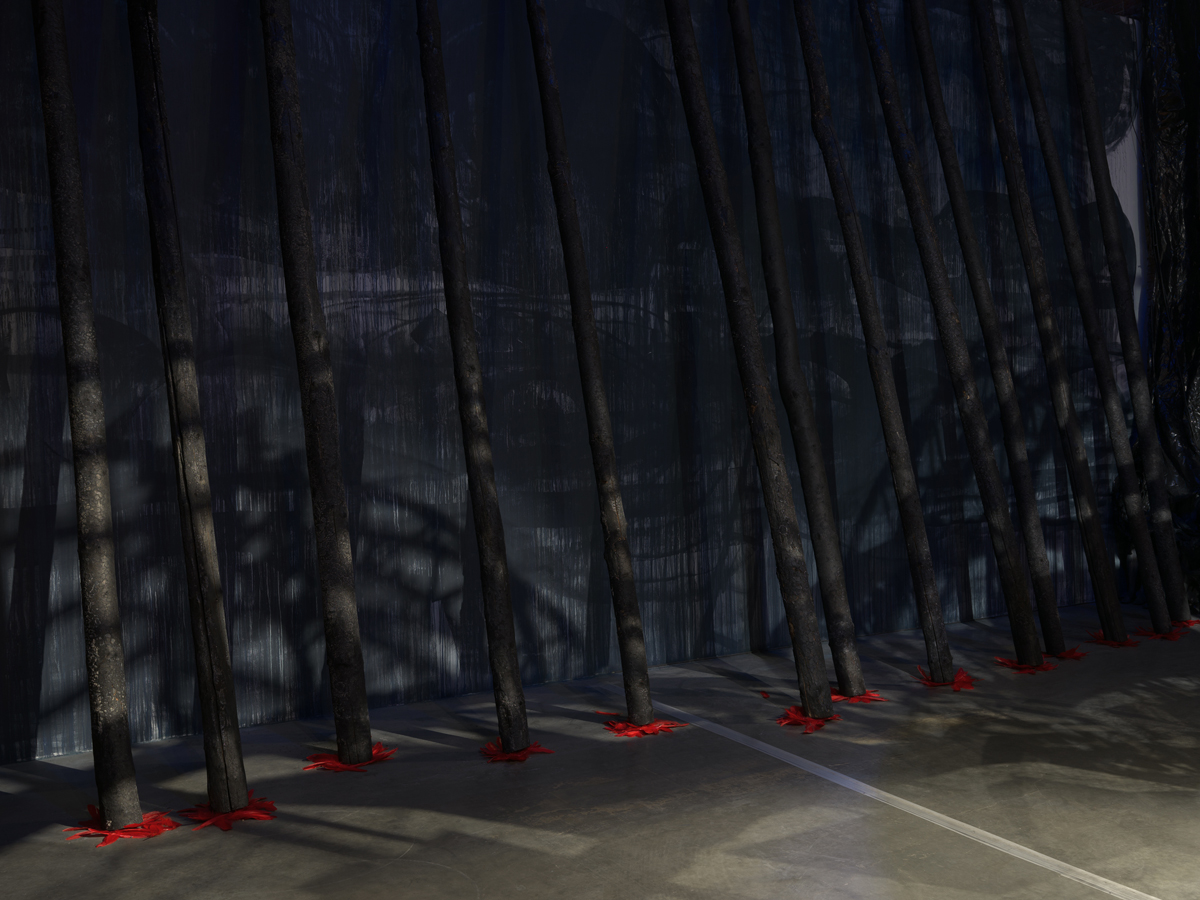

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

One of the gallery walls next to the structure is covered with a perforated, tarry, black plastic, like a theatrical scrim. Casts of legs and feet, mostly painted black, peek out from below, as if they were waiting in the wings to fully enter the stage. Another wall is painted with sweeping, gestural strokes of dark-blue paint; against it lean thirteen liberty poles—one for each of the original colonies. Instead of the red cap of freedom mounted on their tips, these symbols of the American Revolution have been inverted so that they impale clusters of red feathers on the ground. The Observatory is a stark reminder, despite our horror at watching the events of January unfold, that American democracy has always encoded violence and, in its exclusion of many, has never been a true democratic state.

Brand New Heavies, installation view. Courtesy the artists and Pioneer Works. Photo: Olympia Shannon / Dan Bradica Studio.

There are many things that connect the work on view here, both formal and conceptual, but perhaps the most striking is the way that all three artists have created enclosures: spaces in which to contemplate what’s often left unsaid. In them, Blackness is revealed to be the motor that drives so many of our narratives, from fiction, to history, to the stories we tell ourselves about why we continue to fight.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She is co-curator of Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at the Brooklyn Museum of Art; editor of Lorraine O’Grady’s book Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2020); and a contributor to the New York Times. In 2020, she received a Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.