Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The artist asks what it takes for us to care.

Candice Breitz, Love Story, 2016. 7-channel installation. Image courtesy Goodman Gallery, Kaufmann Repetto + KOW, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Candice Breitz: Love Story, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 465 Huntington Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts, through January 21, 2019

• • •

It’s hard to tear your eyes away from the minimally made-up, undeniably beautiful, and vulnerably aging face of Julianne Moore, or from Alec Baldwin’s equally fascinating, doughy mien, in Candice Breitz’s Love Story (2016), a two-room installation on view at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. One enters a darkened gallery where Moore and Baldwin appear by turns on a large screen in the first room of the piece, sitting in director’s chairs against a green-screen backdrop, with a few lights, bounce cards, and mics visible as the camera moves back and forth from a tight focus on each of their shoulders and faces to something closer to a full-length view. The film cuts from Moore to Baldwin and back again, edited in such a precise way that it almost seems like their individual monologues are in fact a conversation, one that switches between Moore’s crystalline tone and Baldwin’s deep thespian rumbling, between hesitation and passion, between a self-deprecating gallows humor and an almost numbing recollection of horror and tragedy. We seem to be offered startlingly intimate access to these Hollywood icons, a sense of their innermost selves, as they each pour out their hearts to the camera.

Candice Breitz, Love Story, 2016. 7-channel installation. Image courtesy Goodman Gallery, Kaufmann Repetto + KOW, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

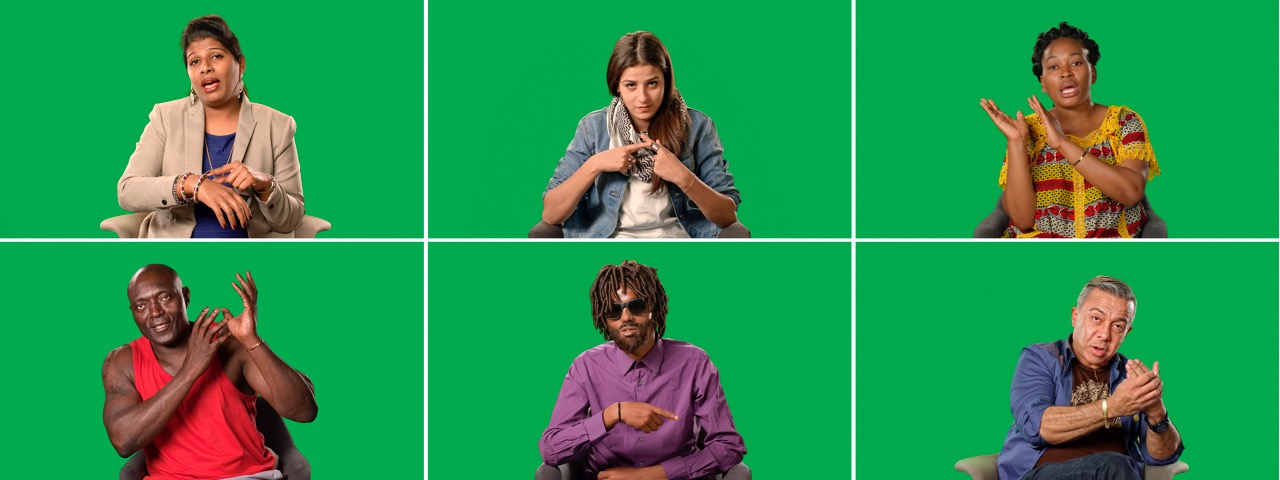

If the subtle changes in voice, in body language, in accessories (a bejeweled pair of bracelets, a gold pin, a silver ring, etc.) from cut to cut isn’t enough to signal that this intimacy is not what it seems, the stories coming out of Moore’s and Baldwin’s mouths surely are: it is impossible to imagine that either of these figures of privilege, wealth, and influence would have ever experienced the horrors that they recount. Indeed, as becomes clear over the course of the seventy-three-minute montage (the length, not coincidentally, of a feature film)—and even clearer when you pass through a doorway into the back room of the installation—the stars are not telling their own stories at all. In the low-lit inner chamber, one finds six smaller screens, each showing a different person speaking to the camera in set-ups identical to Moore’s and Baldwin’s, giving accounts of how they—non-famous people, individuals from around the globe—have been forced by various exigencies to flee their homes. These are the testimonies that Moore and Baldwin ventriloquize. A South Asian transgender woman, a Venezuelan who refused to shy away from criticizing Chavez, a Somali atheist, a Congolese woman whose husband suddenly found himself on the wrong side of the political divide, an Angolan man recruited into mercenary armies as a child, a young Syrian woman who swam for the national team—we hear these refugees’ stories, now largely unedited (each runs to over three hours), unvarnished, and in a sense unacted, told by bodies that have truly experienced the stresses and barbarities of being uprooted, thrust into motion by circumstances that, despite their vivid particularities, form part of the current global refugee crisis. The recordings give new meaning to the term “raw footage”—the footage, and the realities that lie behind it, are raw in the truest sense.

Candice Breitz, Love Story, 2016. 7-channel installation. Image courtesy Goodman Gallery, Kaufmann Repetto + KOW, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Love Story plays with the ideas of empathy, authenticity, and spectacle: what does it take for us, as viewers, to pay attention to the lives of people—68.5 million, according to the UN, more than 25 million of whom are classified as refugees—who have been driven from their homes due to political, economic, and environmental pressures? Does hearing of the crisis via these undeniably talented actors, in condensed form and cleverly edited, allow us to heed it in ways we wouldn’t otherwise? (To be sure, the length of the interviews of the actual migrants in the second room—over eighteen hours’ worth—would make it impossible for an art viewer to watch them in their entirety without making several trips to the show.) Is our propensity to pay attention to Moore and Baldwin a worthwhile means to trigger our empathy and understanding of the refugees’ plight, or a critical condemnation of our willingness to listen only to the famous, the spectacularized—and, most troublingly, the white—subject about circumstances that are destroying the lives of black and brown human beings?

These questions emerge in the course of Moore’s and Baldwin’s intercut monologues. At one point, the actors, playing the characters of the real-life refugees, respond to a question (clearly posed by an off-camera Candice, as they call her, though her voice isn’t heard) about what they hope Moore’s and Baldwin’s rendition of their narratives might achieve. To see the actors mouthing by turn the migrants’ admissions that they don’t really know who Moore or Baldwin are, declaring their hope that the world will listen if famous people tell their stories, expressing their belief in the power of celebrity to advance political causes, revealing their star-struckness, or—in the case of the Venezuelan academic and political dissident Luis Ernesto Nava Molero—railing against the Hollywoodization of the public sphere and our mindless manipulation by movie stars, is hilarious and poignant and heart-wrenching and cringe-inducing all at once.

Candice Breitz, Love Story, 2016. 7-channel installation. Image courtesy Goodman Gallery, Kaufmann Repetto + KOW, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The setup Breitz has concocted for Love Story—green screen, visible if minimal equipment, direct address to the camera, focus on face and hands—is familiar to us: it is the trope of the filmed confessional monologue. It’s a staple of video art, of reality TV (where the subjects of highly edited shows speak straight from the heart, as it were, coercing us to see them, and the production, as, well, “real”). It is also a fixture of police procedurals (where criminals admit to their crimes, either in the interrogation room or as a taunt to their pursuers). There is, though, another realm in which people are required to confess their stories, sometimes on camera though mostly not—in their application for asylum. Over the course of the seventy-three minutes of Love Story, more than one of the interviewees portrayed by Moore and Baldwin note the similarities between what Breitz is asking them to do in order to cast light on the global crisis and what they are compelled to do in front of immigration officers, whether in New York or Berlin or South Africa or countless other ports of entry: tell their stories—stories that include brutal rapes, torture, beatings, painful family separations, daily humiliations, and constant, terrorizing fear—in order to justify their right to cross borders and find safety.

As the parallel is drawn out in the installation, we, the viewers, are pressed by the artist to account for ourselves as witnesses to the devastating impact of humanitarian crises. Can empathy be an effective tool in political transformation, Love Story asks, if it requires those who are suffering to repeatedly narrate their pain? And to what extent does our empathy require a certain version of that story and a certain kind of storyteller? In this sense, the artist’s title is perfectly apt: it describes the perseverance of her subjects in the face of almost unimaginable hardship (as Breitz puts it, “a love for life, a love for family, a love for god, a love for expression, a love for being on this fucked-up planet despite everything”), while making reference to that piece of 1970s cinematic ur-schmaltz starring Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw, a film that jerked a thousand tears out of us, that made us “feel” despite its clichés, its too-predictable storyline, its manufactured emotions.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her new book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.