Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

In the artist’s retrospective at the Hammer, politics is not identity.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, installation view. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, through May 7, 2017

• • •

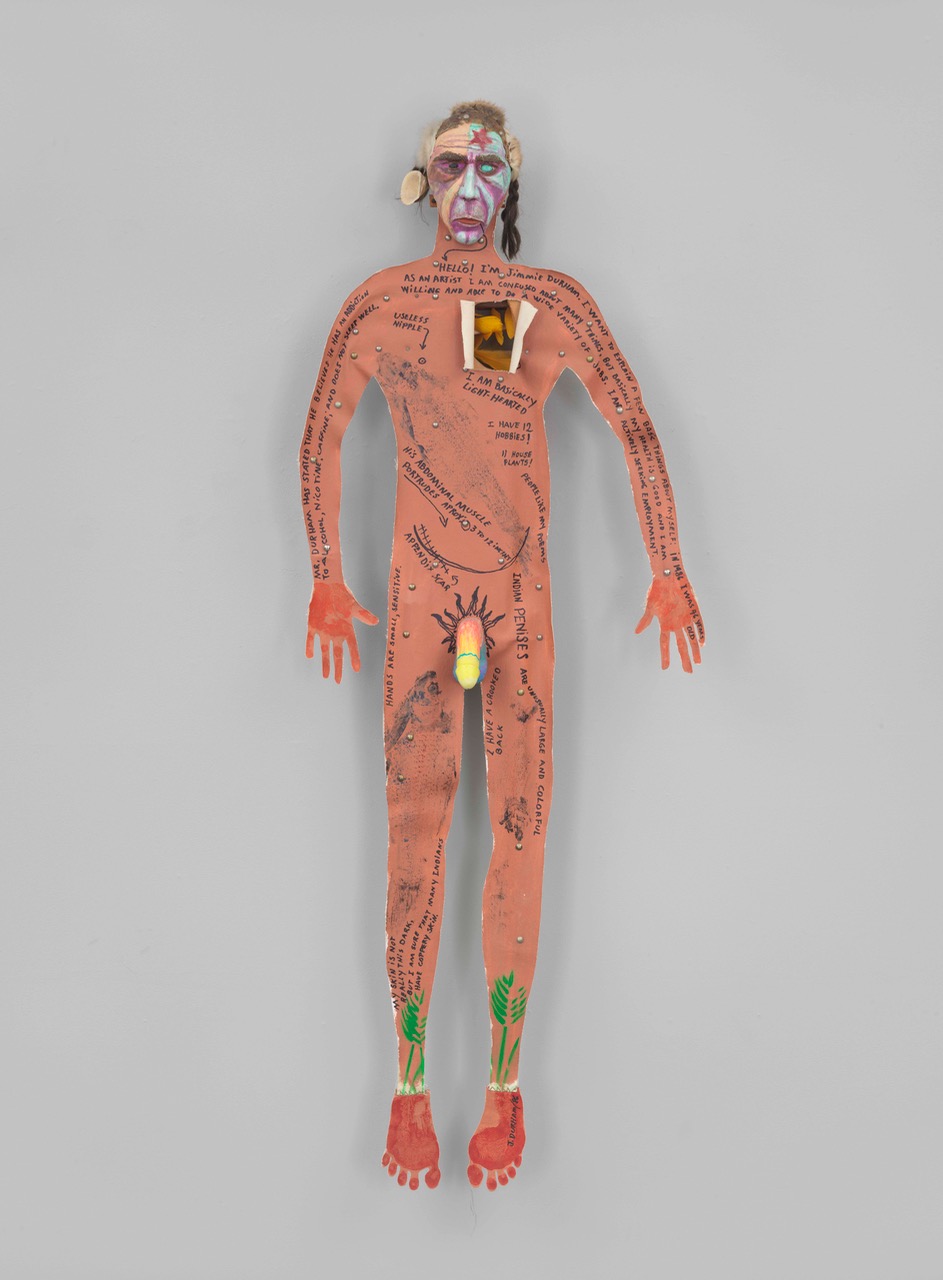

Among the almost two-hundred works in Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World—astonishingly, the first US museum retrospective of an artist who played a key role in the postmodern turn of the 1980s—is his Self-portrait from 1986. The sculpture, which hangs from a nail on the wall, is made of canvas traced from Durham’s body, cut out and attached to a “skeleton” of found wooden and metal objects using upholstery tacks; it is painted a lurid, coppery red. The face is a wooden mask, again painted, perhaps to emulate some sort of Hollywood version of war paint, with synthetic hair and fur to stand for a braid, and turquoise beads and shells to indicate eyes and ears; the figure sports an impressive rainbow-hued wooden penis, too. It is covered with text, this body, words in two different registers, two different voices—one of a clinician, perhaps a doctor or an anthropologist, and one that reads as Jimmie Durham’s own. The first makes “objective” observations about the figure—“Mr. Durham has stated he believes he has an addiction to alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine, and does not sleep well”; “Appendix scar”; “Useless nipple.” The second seeks to explain himself in a way that sounds like someone trying to put others at ease by being a shade too friendly and relatable: “I’m basically lighthearted”; “I have 12 hobbies! 11 houseplants!”; “People like my poems.”

Jimmie Durham, Self-portrait, 1986. Canvas, cedar, acrylic paint, metal, synthetic hair, scrap fur, dyed chicken feathers, human rib bones, sheep bones, seashell, thread, 78 × 30 × 9 inches. Image courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

The piece is a self-portrait of Durham as “Cherokee artist”—a label that has dogged him throughout his career, and one that he has tried to escape in many ways, though his work has always dwelt unapologetically on issues of American Indian politics and settler colonialism. But politics is not identity, in Durham’s telling. Like so much of his work, this self-portrait refuses the idea of identity except as an accumulation of stereotypes and signifiers: he is defined by the words painted on his body, by found objects, and by voices that are clearly not his own. (I’ve never met Durham, but I’ve got a pretty good idea that he doesn’t often express himself in the chirpy tone found in the text covering the self-portrait.) His identity, the piece seems to imply, has nothing to do with him and everything to do with the fantasies and needs of the dominant culture—its need, that is, to define, to explain, to rationalize, and to compartmentalize difference, preferably with the subject’s enthusiastic cooperation.

Indeed, over the course of his career, Durham rejected the many ways in which he was asked to account for himself—whether by the art establishment, by factions within the American Indian community, by the strictures of a white hegemony, or indeed by the state. When, in 1990, George H.W. Bush signed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, a truth-in-advertising law that requires galleries selling work by American Indians to provide documentary proof of the artist’s tribal affiliation, Durham, who had long refused to register as a member of the Cherokee Nation, had two exhibitions cancelled by galleries specializing in American Indian art. He made the following statement at the time, one that mocks the question of affiliation, identity, and authenticity: “I am a full-blood contemporary artist, of the subgroup (or clan) called sculptors. I am not an American Indian, nor have I ever seen or sworn loyalty to India. I am not a ‘Native American,’ nor do I feel that ‘America’ has any right to either name me or un-name me. I have previously stated that I should be considered a mixed-blood; that is, I claim to be a male, but only one of my parents was male.” It reads like an identity politics Mad Lib: just substitute other terms and the inanity of the obligation to constantly name one’s difference becomes painfully clear.

Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World, installation view. Photo: Brian Forrest.

The Hammer exhibition has been curated with care by Anne Ellegood. Roughly chronological, it includes nearly fifty years’ worth of activities, including: found-object assemblages that combine urban detritus culled from Durham’s walks through New York City (traffic pylons, police barricades, random car parts) with signifiers of “Indian art” (skulls, feathers, animal skins); object-filled vitrines that parody the conventions of natural history museums; sculpted objects that demonstrate his proximity and distance from European modernism (his Anti-Brancusi from 2005 is made of stacked boxes, including one for a urinal bowl, for example); videos and films that span his whole career; and so on. The show was the result of years of conversation between Ellegood and Durham: while Ellegood quite rightly wanted to demonstrate the sculptor’s centrality to artistic developments here in the 1980s—ranging from institutional critique to video to performance—Durham was as resistant to being defined as an “American artist” as he was to being labeled an “American Indian artist”; in fact, he had decided to leave the US, first, in 1987, to Mexico, and then, in 1994, to Europe, in protest of the country’s treatment of its native population. As he has put it in interviews, eventually Ellegood wore him down—which is surely luck for us.

Jimmie Durham, Anti-Brancusi, 2005. Cardboard, wood, serpentine stone, rope, ink on paper, 48 × 17 × 31 ⅛ inches. Image courtesy collection of Michel Rein.

Instead, the show floats the concept of “post-American” to account for the contradictions embodied in Durham’s work and life. To be American Indian seems to mean, for Durham, a kind of cosmopolitanism or statelessness that defies attempts to essentialize or locate it within the terms of a nation—both by the US government, as well as by the American Indian Movement, with whom he eventually broke in 1980 after playing a major leadership role for years. The title of the exhibition is derived from a series of works the artist has been making since 1995, in which he carves tree branches, attaches a mirror to them with a string, and titles them A Pole to Mark the Center of the World, followed by the name of the city in which he made them (and often posed with them in photographs)—Middelburg, Brussels, Berlin, etc. The work seems to parody both the self-regard of Western humanist traditions and the postmodern handwringing over center and periphery (a concern that mostly left such power relations firmly intact). It is also, in its futile repetition—the center of the world is as peripatetic as the artist himself—a reflection on what is lost when we imagine ourselves only through the lenses of inside and outside, a sort of performance of the artist’s 1988 lament (or is it a boast?), “I feel fairly sure that I could address the entire world if only I had a place to stand.”

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and The Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson, and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.