Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

From Ethel Rosenberg to the war at home: an exhibition explores the feminist artist’s long career.

Martha Rosler: Irrespective, installation view. Photo: Jason Mandella. Artwork © Martha Rosler.

Martha Rosler: Irrespective, the Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through March 3, 2019

• • •

Martha Rosler: Irrespective, an exhibition of works spanning the astonishing breadth of the artist’s fifty-plus-year career, is a tightly curated, highly focused exhibition—a survey organized around a discrete set of themes Rosler engages (war, consumerism, domesticity, politics, and mass media, to name a few) rather than a full retrospective. The show makes clear that no matter where her curiosities take her, no matter what her medium (photography, film and video, collage, sculpture, installation), Rosler’s work is incredibly consistent in its political commitments, its activist impulse, and its ability to combine extreme seriousness with a sense of humor and playfulness.

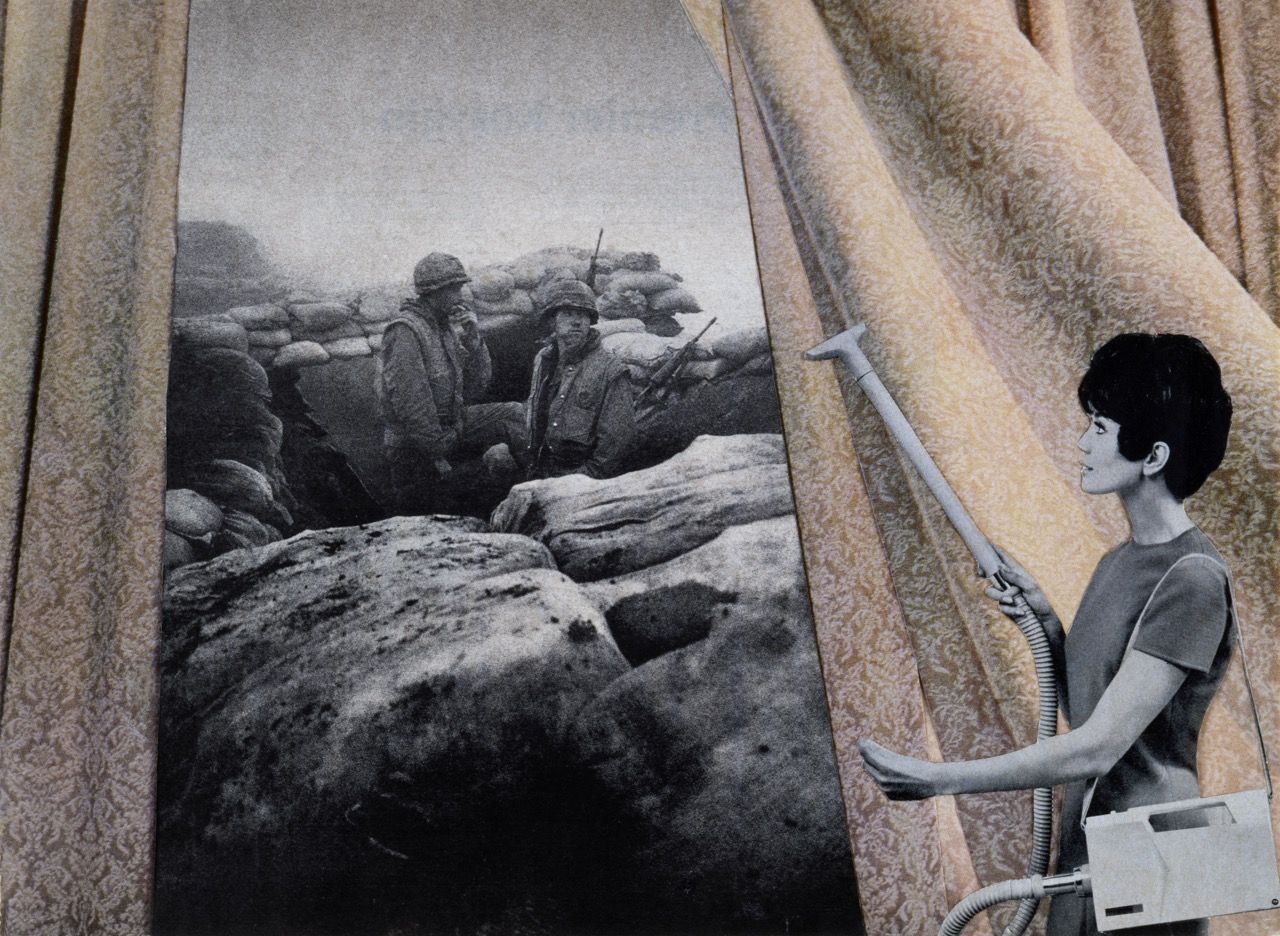

Martha Rosler, Cleaning the Drapes, from House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c. 1967–72. Photomontage. © Martha Rosler.

This consistency—which should not be mistaken for repetitiveness, by any means—is perhaps best demonstrated by one of Rosler’s most famous series, which dominates the first room in the exhibition: House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home. She embarked on the work around 1967, cutting out photographs of the Vietnam War that appeared in the popular press and inserting them into images culled from women’s magazines of fashionable and well-appointed domestic spaces; she would photocopy and distribute them at anti-war protests. The photomontages play on the conventional wisdom of the era that Vietnam was the country’s first “living room war,” thanks to daily broadcasts on that newly ubiquitous technology, the television. Her photomontages transformed her source photos into dadaistic horror shows, in which images of violence were no longer bounded and sanitized by the TV screen but now peeked through picture windows, blocked doorways, and hung over mantlepieces. She revived the series in 2003, 2004, and 2008, during the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; that Rosler’s conceit landed with such force forty years after its original deployment is telling. Sure, the women in these works wear different fashions than the Vietnam versions of House Beautiful and wield selfie-taking camera phones rather than vacuum cleaners, but the imperialist, profit-fueled death and destruction collaged into these later images are troublingly the same. We haven’t lost our taste for war, Rosler points out, any more than we’ve lost our taste for the mid-century modern aesthetic and retro Eames chairs that occupy these on-trend interiors.

Martha Rosler, Photo-Op, 2004, from House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series. Photomontage. © Martha Rosler.

Taken together with another photomontage series, Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (1966–72)—in which images from Playboy, fashion magazines, and advertisements are often overlaid with amputated breasts and pubes and lips, turning erotic display into a form of violence—House Beautiful seems to fit right in with a women’s lib–fueled consciousness-raising approach to media culture. At first glance, that is to say, these series point out the ways in which middle-class women are stuffed into limited gender roles as either sex objects or housewives, dissect the unrealistic beauty expectations imposed on them, and so on. But look again at the blitheness with which the figures in House Beautiful preside over their domains while war rages on all around them, and a different reading emerges. In these and other works in the show we see the full force of Rosler’s feminist challenge: rather than simply imagining women as victims of patriarchy, she continually points out the ways in which they participate in the reproduction of patriarchal forms of oppression, knowingly or not.

Take, for example, Diaper Pattern (1973). The piece is composed of thirty of her son’s cloth nappies, hung in a grid from a metal rod. On the diapers are written comments, real and imagined, from soldiers and supporters of the Vietnam War—comments filled with casual and not-so-casual racism, making clear that for all the rhetoric around democracy and freedom this was a conflict fueled by a toxic, hateful machismo. The wall label states that this work speaks of “the public politicized aspect to childcare and other domestic labor typically performed by women,” but what does this politics actually entail? Especially for viewers still raw from the Kavanaugh hearings—which prompted a wave of women to loudly lament the possibility that their sons would be victim of false accusations, with seemingly little concern about the fate of their daughters, countering #MeToo with #DefendOurMen—Rosler’s quilt of hate speech reminds us of the women who birthed, cared for, and nurtured these men, tending to their shit as infants, and later loving them despite (or sometimes for) their shit talk as adults.

Martha Rosler, Unknown Secrets (The Secret of the Rosenbergs), 1988. Installation with screenprinted black-and-white photographs on canvas, wooden towel rack with stenciled towel and Jell-O box, and printed text handout. © Martha Rosler.

A few steps away from Diaper Pattern we see another piece that includes a well-washed piece of linen: Unknown Secrets (The Secret of the Rosenbergs) (1988). The installation centers upon a canvas screen printed with mass-media images and advertising images related, sometimes glancingly and sometimes directly, to the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the young Jewish couple convicted of being Soviet spies in the 1950s. At the center of the canvas is a photo of Ethel in her kitchen, drying her dishes. Nearby is a towel rack on which sits a box of Jell-O (a key bit of “evidence” brought to bear in the trial) and a cotton dish towel printed with the text of a letter from President Eisenhower to his son, written three days before the Rosenbergs’ execution in 1953, explaining his refusal to commute her sentence. The words, stenciled in red, speak to the demonization of Ethel in particular based on her gender, a demonization that led to her unjust conviction; the other aspects of the installation suggest that it was her unwillingness to remain bound within the domestic sphere that determined her fate.

Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen (still), 1975. Black-and-white video, 6 minutes 13 seconds. © Martha Rosler.

The installation of this show—roughly chronological, sensitive, jam-packed—and the circular design of the galleries allows for a sense of flow from one set of ideas to the next. The unflinching works on women, domesticity, and geopolitics lead to a room filled with Rosler’s often-hilarious explorations of food culture. These include the six-minute video Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), in which the artist stands in a modest kitchen wearing an apron, identifying a series of common kitchen implements and their uses, her calm deadpan becoming increasingly frenzied as her pent-up anger becomes apparent. In the same room we find the 1974 installation A Gourmet Experience, a novel in the form of postcards called A Budding gourmet from the same year, and North American Waitress, Coffee-Shop Variety of 1976, from the Know Your Servant Series. The works are scathing, funny, and prescient—decades before Michael Pollan and his ilk turned their attention to the economy, ethics, and sustainability of food production, Rosler was deconstructing the Julia Child-ification of the middle-class American housewife through the lenses of class, race, and gender.

Martha Rosler: Irrespective, installation view. Photo: Jason Mandella. Artwork © Martha Rosler.

The show’s circularity produces its greatest impact in its last and first rooms: we go from Rosler’s Bush-, Obama-, and Trump-era reflections of war, violence, and political theory (including a 2006 installation of vinyl panels titled Reading Hannah Arendt [Politically for an Artist in the 21st Century]) back into the first gallery. Here, in addition to House Beautiful and blow-ups of Body Beautiful—images of battleground mortality and cut-up female bodies—we discover Prototype (Freedom Is Not Free) (2006). An oversized, motorized prosthetic leg, similar to ones produced for veterans of the endless American wars of the recent decades, swings from the ceiling as if enacting an endless session of post-traumatic physiotherapy. Nearby, a computer-animated video of a soldier toots out “God Bless America” on a trumpet. The interconnectedness of themes from the earliest moments of her career to her much later work is a bracing realization of how little we’ve learned in the course of half a century, and how profound, and even prophetic, Rosler’s analysis has been every step of the way.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her new book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.