Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Baby strollers and the diaspora: the New Museum hosts a retrospective of the artist’s work.

Nari Ward, Amazing Grace, 1993. Approximately 300 baby strollers and fire hoses, dimensions variable. Installation view: NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, New Museum, 2013. Image courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin. Photo: Jesse Untracht-Oakner.

Nari Ward: We the People, the New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through May 26, 2019

• • •

Nari Ward immigrated to New Jersey from Jamaica at twelve, went to art school in and around New York City in the late 1980s, began making sculpture in 1991, and was a full-fledged member of the Art World by 1993. (In a period of just a year, he was awarded a prestigious residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, was featured at the New Museum, and participated in the Venice Biennale.) From its debut, his practice has involved the use of scavenged material, often gleaned from the Harlem neighborhood in which he has lived and worked for decades. He has been a keen observer of the accidental aesthetics of street life, including, for example, the way that homeless people pile shopping carts and baby strollers with their foraged finds, turning these means of survival into wondrous objects. He has long held an interest in the African diaspora—the result of colonialism and the slave trade and exile and immigration and, lately, gentrification—and the way such scattering of people over time and geography has resulted in syncretic cultural forms.

But despite the endurance of his themes, the interpretation of his practice has frequently shifted to satisfy the latest curatorial and critical paradigms. He’s been seen as everything from a multiculti postmodern purveyor of identity politics to a cool post-black formalist to a peripatetic globalist to an heir of a particular West Coast strain of the black aesthetic that relies on found objects. And now, in his New Museum retrospective, Ward is presented—via a careful pruning of his output to forty-two featured pieces and a thoughtful catalog—as an artist whose deep engagement with the local and culturally specific refracts current crises of forced migration, exile, and loss of home.

Nari Ward: We the People, installation view, New Museum. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio. Pictured: Amazing Grace, 1993.

None of these characterizations are necessarily wrong, mind you. Take Amazing Grace, which occupies a large room in one of the exhibition’s first galleries. The fruit of his 1992–93 Studio Museum residency, first installed in an empty firehouse in Harlem, it positively invites myriad associations: hundreds of baby strollers, abandoned on sidewalks and in dumpsters, gathered into an ovoid form that is somewhat like a ship’s hull, with paths delineated by flattened, dirt-stained fire hoses allowing you to traverse the installation. A recording of Mahalia Jackson singing the eponymous hymn, the dim, almost churchlike illumination, and the recollection of the tiny bodies that once filled these strollers conjure an almost unbearable sense of loss here—but what, exactly, are we mourning? Those who died because of the AIDS and crack epidemics that devastated New York’s black communities in the early 1990s? The thousands and thousands who have died—and the countless more that have suffered—as a result of the slave trade? The current plight of millions of people—yes, even babies—who have been driven from their homes all over the world because of political, economic, and environmental upheavals, and consigned to the perpetual limbo of the refugee?

Nari Ward: We the People, installation view, New Museum. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio. Pictured: Carpet Angel, 1992.

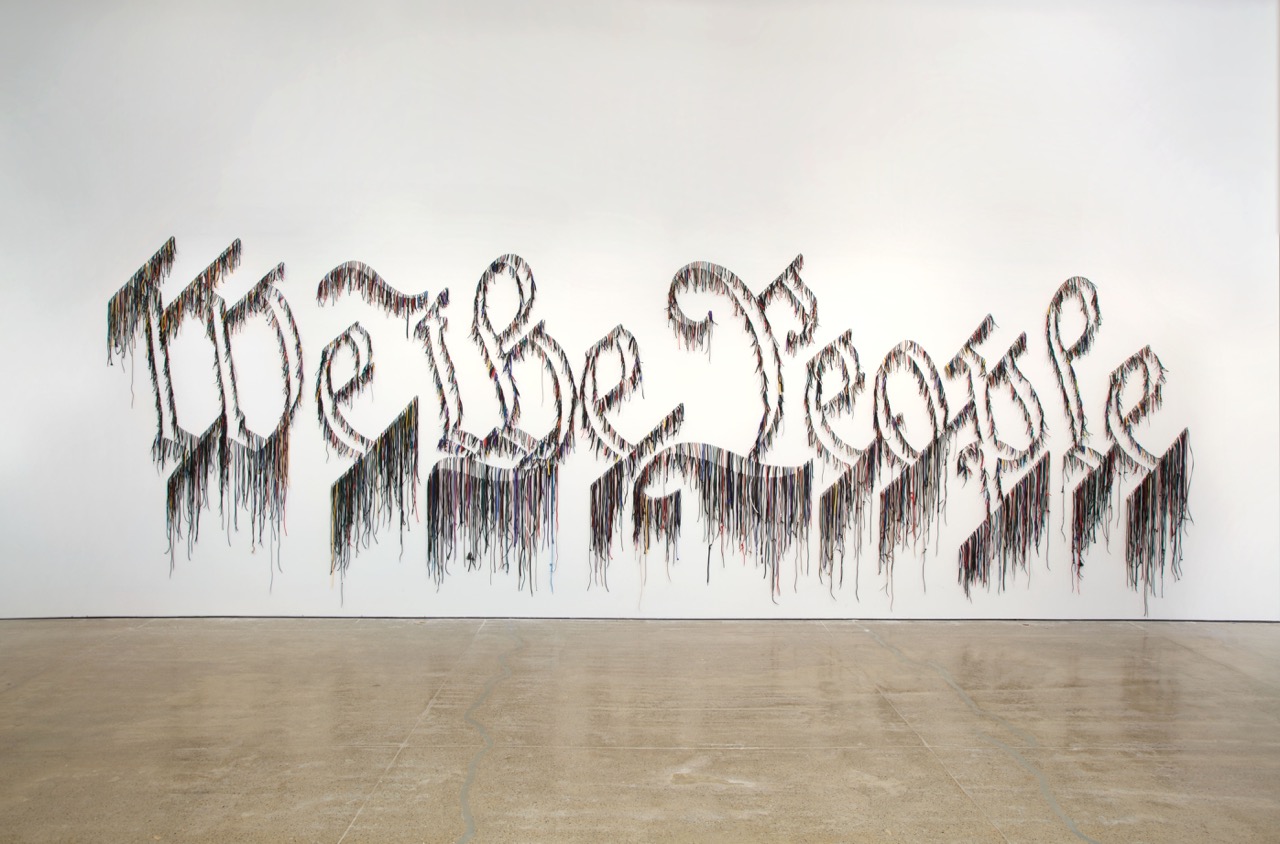

The same open-endedness characterizes much of the work that launched Ward’s career: Carpet Angel (shown in that 1993 debut at the New Museum) repurposes the rugs left by a previous tenant in his then-new studio into an abstracted angelic form, evoking spirituality through these discarded objects; Exodus (made for the 1993 Venice Biennale) speaks to diaspora and displacement—among many other things—with blocks of cast-off clothes and other items bundled up with flattened fire hose, scattered around the gallery floor, all oriented toward a gorgeous fabric mandala-like relief on the far wall. Even a later installation—2011’s We the People, which lends its title to his retrospective—cannot be pinned down: yes, these are the introductory words of the US Constitution, but when spelled out in individual colored shoelaces implanted into the wall and spilling down below, they suggest readings that range from the joys of multiculturalism to the hopeless fragmentation of the public sphere.

Nari Ward, We the People, 2011. Shoelaces, 96 × 324 inches. In collaboration with the Fabric Workshop and Museum. © The Speed Art Museum.

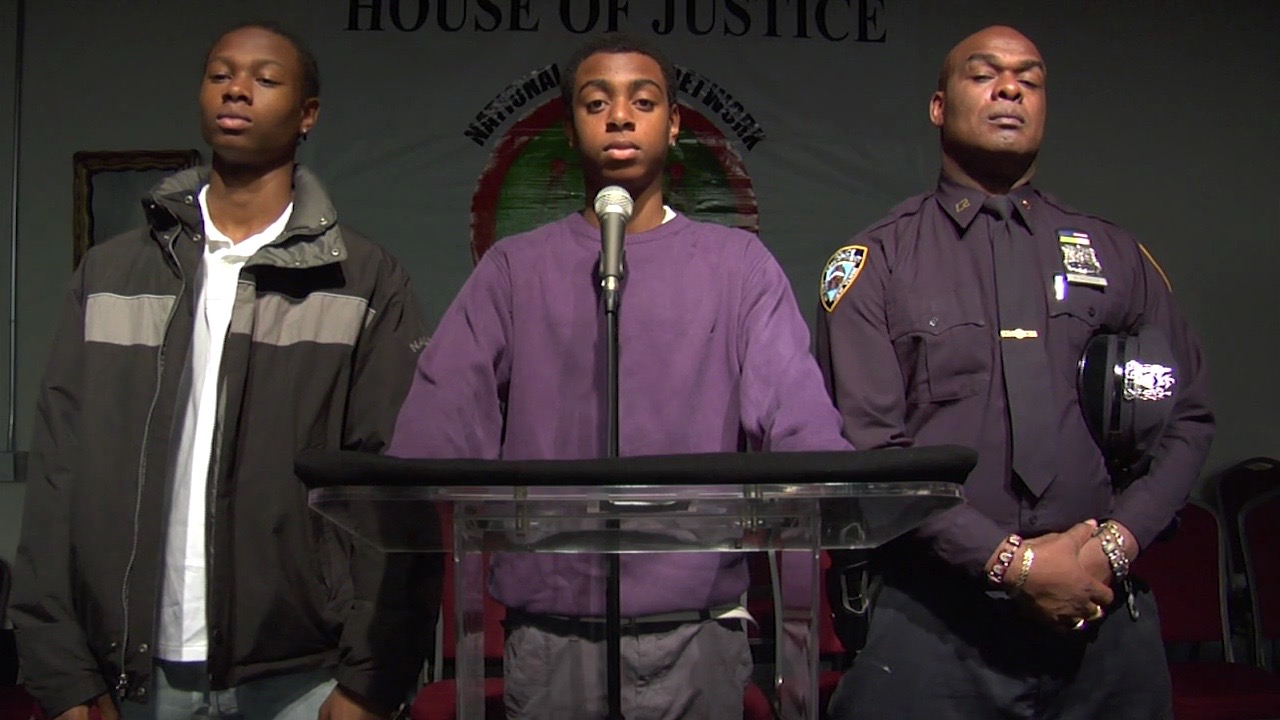

I know we’re supposed to value such multivalency as a sign of great art, but it doesn’t make for great politics, and so its usefulness when it comes to political art is an open question. Ward’s work may seem obviously political from today’s vantage, but it’s interesting that he was not included in the 1993 “identity politics” Whitney Biennial, but was part of the 1995 “corrective” to it—the biennial that intended to bring us back to our purely aesthetic senses. I must admit that I am drawn to the pieces in the show that are less seemingly adaptable to every politically inflected art-world trend. Homeland Sweet Homeland (2012) is one of these—a blinged-out assemblage festooned with eagles, barbed wire, and police bullhorns and printed with the canned responses every young black man needs to commit to memory for when he’s taken into custody by the police. (A video from 2010, Father and Sons, tucked away in the next gallery, depicts the sons of a black police officer reciting these rules from the dais of a small church meeting room while their father looks on. To our eyes, the father ricochets between protector of his children and representative of their oppression. When he stands in uniform beside them, you don’t know if the boys have found safe harbor or if they—if we—should fear for their well-being.)

Nari Ward, Father and Sons, 2010 (still). Digital video projection, sound, color; 3:52 minutes. Filmed by Scott Sinkler. Image courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, and Galleria Continua.

There are other, less didactic pieces, where despite employing more abstract forms, Ward alludes to a specific political and historical context. His series of Breathing Panels from 2015, for example, is composed of constellations of copper nails protruding—in distinct, diamond-shaped formations—from glimmering, galactic painted backgrounds. These works nod to black art history—Jack Whitten haunts them, a benevolent spirit—while referring quite pointedly to the geometrical arrays of air holes drilled into wooden floorboards of churches on the Underground Railroad for refugees who were hidden underneath. The pattern the nineteenth-century freedom fighters chose had migrated along with their ancestors from West Africa. Ward’s oak panels, with their darkening, patinated surfaces, bear witness to the ways in which a very specific culture of resistance has produced an aesthetic of subtle visual languages passed down as a form of survival—a language not untethered from history but dependent on it. In works like these, politics and poetics find common purpose.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her new book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.