Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

With plants, books, multimedia and multimodal works, a nod toward Black survival, liberation, and love.

Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers, installation view. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation.

Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers, curated by Naomi Beckwith and Andrea Karnes with Faith Hunter, Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, through January 18, 2026

• • •

A persistent mood running through A Poem for Deep Thinkers—a mid-career survey of the conceptual, multimodal artist Rashid Johnson, curated by Naomi Beckwith and Andrea Karnes, that fills the entire ramp of the Guggenheim Museum—is anxiety. It is thematized in one of the first pieces we encounter in the show (which includes more than ninety works made over the course of twenty-five-odd years): the visually compelling Untitled Anxious Audience (2019). This mural-size “painting” is made of white ceramic tiles smeared, Twombly-style, with black soap and wax. Into this substrate, Johnson has incised rectangular faces with round scribbled eyes, a brace of bared teeth, and stumpy necks in a not-quite uninterrupted ten-by-seven array—Basquiat guys, but ordered like a Minimalist canvas. The internal chaos of the graffiti-ish, cartoonish characters seems as though it might be brought into provisional control by the structure imposed on them, except for the occasional gaps in the arrangement and the fact that the grid formed by the faces is out of sync with the underlying grid of their ceramic-tile base. This character is repeated in multiple works, including three from 2015, each a singular “portrait,” all called Untitled Anxious Men; an oil-on-animal-skin piece titled Anxious Mask (2019); and Anxious Red Painting “August 18” (2020). He shows up again in mosaics created out of tile, mirror, oyster shells, black soap, wax, oil stick, and spray paint, including Untitled Broken Crowd (2021), The Broken Five (2019), and Untitled Broken Men (2019), and in stoneware and bronze busts, some of them serving as planters.

Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers, installation view. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, center: Untitled Anxious Audience, 2019.

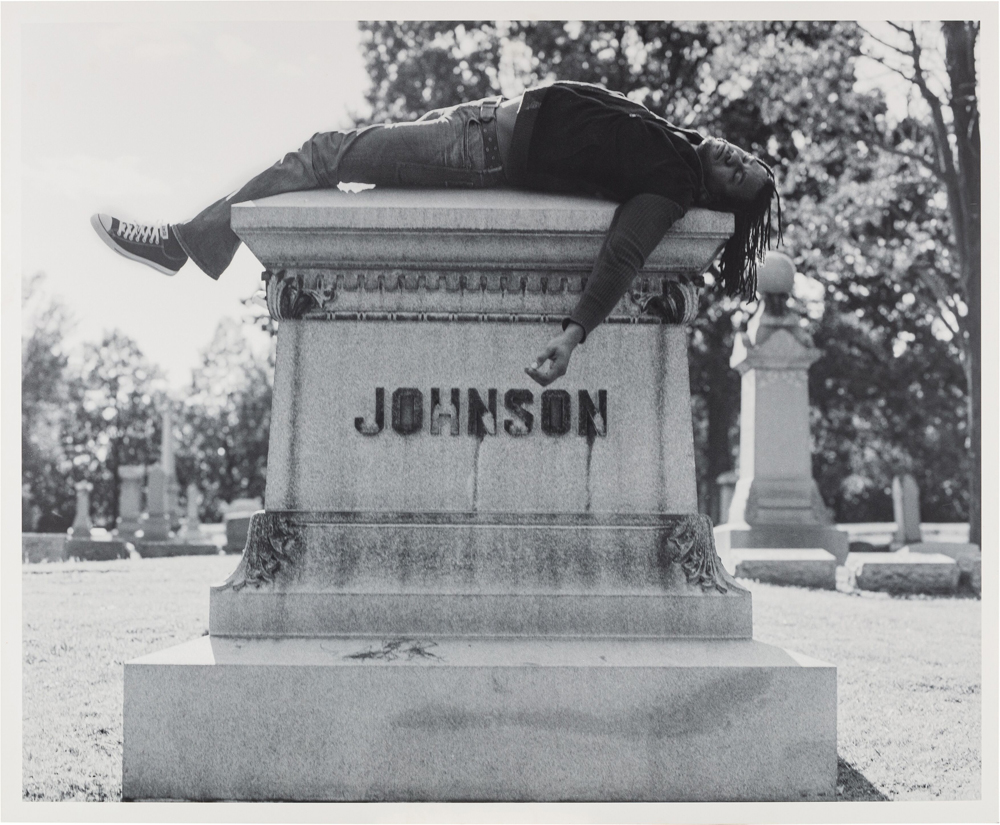

That’s a lot of angst, even despite the gentle humor and sly charm of the chaos faces. And why not? As the sweep of Johnson’s practice reminds us, there are a lot of reasons for Black people, men in particular, to be anxious—not least, the ways in which they are vulnerable to white-supremacist violence, whether discursive, cultural, or literal. When Johnson poses himself, lifeless as a corpse, on the boxer Jack Johnson’s grave in Chicago for a 2006 photograph, or when, as part of his 2005 series Things I need to do, he spray-paints the words “STAY BLACK AND DIE” on a felt panel, he cites this reality.

Rashid Johnson, Self Portrait laying on Jack Johnson’s Grave, 2006. Chromogenic print mounted on panel, 40 1/2 × 49 3/5 inches. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. © Rashid Johnson.

But Johnson offers plenty of possibilities for healing, too. In a 2004 video, Me, Tavis Smiley and Shea Butter, he applies the emollient to his body while listening to NPR. Shea butter and black soap are recurring materials in his work, both tied to rituals of Black self-care, and Smiley, a prominent radio talk-show host who centered structural racism and consequent issues facing the Black community, was an exception in a media landscape too often marred by overt, though unacknowledged, racial bias. Johnson’s series The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club from 2008–09 comprises photographs of the artist and others in the guise of figures like Thurgood Marshall and Emmett Till, though he doesn’t indulge in historical cosplay—they appear as they might today, as potential contemporary companions rather than part of the distant past. (Marshall is depicted enveloped in steam, a reference, per Johnson, to the Chicago bathhouses the artist used to haunt looking for community, and where he once bumped into a stark-naked Jesse Jackson.) The mesmerizing and evocative Black Yoga (2010) involves a television monitor set on a Persian rug; the almost five-minute-long video shows the artist performing asanas that seamlessly morph into hip-hop dance steps and martial-arts moves, a deracination of the South Asian–origin, white-appropriated practice that makes room for his own Black body.

Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers, installation view. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, center right on rotunda wall: The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Emmett), 2008.

Two more videos, Black and Blue (2021) and Sanguine (2024), the first featuring his wife, the artist Sheree Hovsepian, and son, and the second, his father and son, home in on the space of the family. Daily, ordinary rituals of care are interspersed with moments of stylized performance involving masks and other props that speak to ancestral pasts. And then there are the plants—potted in ceramic sculptures, hanging in the rotunda of the museum, parked on room-size constructions of metal shelves along with books and other resonant objects—which require, like Johnson’s own child, a kind of nurturing and care that is constant and loving. One comes away feeling as if Johnson’s whole career has been spent, in the best way possible, building a web of references and reminders, a kind of safety net or cocoon for people who, like him, are figuring out how to survive.

Rashid Johnson, Sanguine, 2024 (still). 35mm film transferred to video, 5 minutes 52 seconds. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. © Rashid Johnson.

Literature is everywhere in this show, starting with its title, A Poem for Deep Thinkers (drawn from a verse by Amiri Baraka), to the recurring image in photographs and film of Johnson reading, to the stacks of books that sit on the shelves of his hybrid object-paintings and installations. Even a partial list of titles that appear here is long: Randall Kennedy’s Sellout; Powers of Healing from the series “Mysteries of the Unknown”; Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Death by Black Hole; Dick Gregory’s Write Me In!; Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life; Bill Cosby’s Fatherhood (an ambivalent guide at best); James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time; Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth; Gwendolyn Brooks’s Blacks and In the Mecca; an Alcoholics Anonymous handbook; LeRoi Jones’s (later Amiri Baraka) The Dead Lecturer; Elizabeth Alexander’s The Black Interior; Debra Dickerson’s The End of Blackness; Claudia Rankine’s Citizen; Paul Beatty’s The Sellout; and, recurrently, Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. (Johnson often includes multiple copies of a publication in a single piece, turning them into modular columns with their cover designs adding notes of color or texture.)

Rashid Johnson: A Poem for Deep Thinkers, installation view. Courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Pictured, center on upper rotunda level: Black Yoga, 2010. Lower left: Contemporary Black Male Literature Starter Kit, 2003 to present.

With a few exceptions, these books might be a bibliography for Black liberation. But in Beckwith’s catalog essay, and in an interview with the painter Odili Donald Odita, Johnson insists he is not an activist—rather, he understands the freedom he’s seeking as an artistic one, a freedom to make what he wants without being limited, as are so many artists whose identities are marked in the white artworld, by the demand to always be “political” in a narrowly defined sense. (The proscription was also promoted by the Black Arts Movement; Johnson was one of a generation of artists dubbed “post-Black” because of their refusal of such strictures.) In fact, the lessons of Johnson’s bibliography seem to shape his work in only oblique ways—as a friend said to me, “It doesn’t seem like he needed to read those books to make the art that those books appear in.” (Please note: this is decidedly different than saying he didn’t read them.) Looking at Contemporary Black Male Literature Starter Kit (2003–) only underlines my feeling that they function more like props or, even better, memes—bite-size morsels of theory rather than a full meal. (Let’s face it: memes are how most of us consume politics these days, Black liberation–oriented or not.) The piece consists of a wooden shipping pallet piled with volumes, unreadable because they are still enveloped in layers and layers of plastic wrap. We are left to wonder, is it a starter kit for personal or collective transformation, or one that is meant to create a vibe of radicality and intellectualism, a form of decor? Despite the often really seductive material intelligence of Johnson’s work, I’m not so sure.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns. Her new book, Imperfect Solidarities, was published by Floating Opera Press last summer.