Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

An exhibit of mixed-media work showcases the artist’s engagement with materiality, ritual, and play, now on long-term view at Dia Beacon.

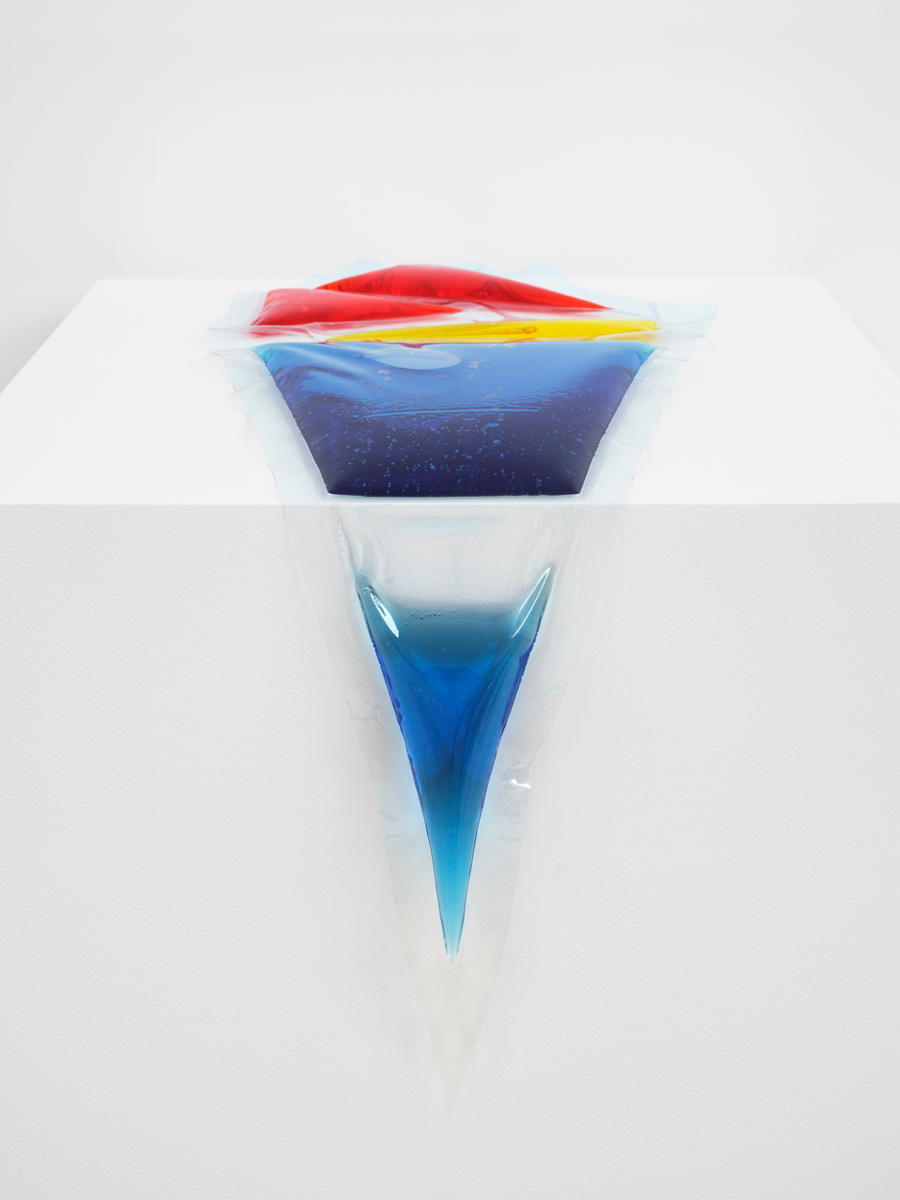

Senga Nengudi, Wet Night–Early Dawn–Scat Chant–Pilgrim’s Song, 1996. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Senga Nengudi.

Senga Nengudi, curated by Matilde Guidelli-Guidi, Dia Beacon,

3 Beekman Street, Beacon, New York, on long-term view

• • •

In her nomination of Senga Nengudi for a show at Artist’s Space in 1993, Lorraine O’Grady wrote that her friend “can fit into a suitcase an art installation more important than others can erect with earth-moving machines.” This proposition is put to the test in a new long-term exhibition of Nengudi’s work at Dia Beacon—an institution filled with pieces of art that, if not literally made with bulldozers and dump trucks, share a certain DNA with (and are part of the same collection as) those Robert Smithsons, Michael Heizers, Walter de Marias, and Nancy Holts that must have been on O’Grady’s mind. Centering on six Water Compositions—some of Nengudi’s earliest exhibited works, from around 1970—and two room-size mixed-media pieces—Wet Night–Early Dawn–Scat Chant–Pilgrim’s Song, from 1996, and Sandmining B, from 2020—the show demonstrates that, as usual, O’Grady was right.

Senga Nengudi, Wet Night–Early Dawn–Scat Chant–Pilgrim’s Song, 1996 (detail). Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Senga Nengudi.

The Dia Foundation’s permanent collection is extremely focused, including only about three dozen artists active during the 1960s and 1970s—mostly male, mostly white, mostly American and European—working in Minimalist, Postminimalist, and Conceptual modes. In recent years, the collection has expanded to include a larger array of makers, whose practices both deepen and refract the institution’s aesthetic “brand,” including Melvin Edwards, Mary Corse, and Michelle Stuart. Nengudi is the first Black woman to become part of this circle. (Dia has acquired all but three of the pieces in this show.)

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition III, 1970/2018. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Senga Nengudi.

Long a central figure in Black avant-garde circles, Nengudi taught at the Watts Towers Arts Center in Los Angeles in the late 1960s (alongside Noah Purifoy, John Outterbridge, and Judson Powell) and had her first solo show at Just Above Midtown gallery (JAM) in New York in 1977. She shared studios with David Hammons and Maren Hassinger at various points and collaborated with them both. In recent years, her work has become more widely known—she received the Nasher Prize for sculpture this year—especially her remarkable R.S.V.P. sculptures, made between 1975 and the early 1980s. Composed of used pantyhose filled with sand and other materials, hanging from walls under the weight of gravity or stretched and pinned to the floor in various ways, and sometimes activated by Hassinger in performances for the camera, they allude to the body—tangentially invoking breasts, bellies, balls, and bums—while remaining wholly abstract. (Her interest in the relationship between material and action was gleaned in part from her study in Tokyo in the mid-1960s, where she came across the work of the Gutai group.)

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition (multicolor), 1969/2021. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Senga Nengudi.

The show at Dia Beacon gives us insight into what Nengudi was doing before she made the R.S.V.P. works (which are not displayed here) and where her practice has gone since. The Water Compositions predate the pantyhose sculptures by a few years (originally made in 1969 and 1970, and refashioned more recently) but share the same fascination with malleable materials and provisional forms that evoke visceral experience. Flat transparent vinyl shapes juicy with brightly colored liquids lie on low platforms, drape over boxy pedestals, or hang from ropes anchored to the wall so that their watery weight settles on the ground. The artist has twisted some of the shapes to provide structure to the fluid inside. Look closely and you can see effervescence, like glitter or constellations of stars, accumulated between water and plastic.

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition I, 1970/2019. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Senga Nengudi.

These sculptures play with so many of the ideas that were circulating in Nengudi’s artistic moment, especially around Minimalism and Postminimalism. Take Water Composition (green/yellow) (1969–70/2018). Its four plank-like vinyl shapes placed at slight angles to each other suggest an interest in modularity not unlike that of the murderous Carl Andre’s Lever (1966), for which he arranged 139 firebricks in a line. The liquid-filled pouches of Water Composition I, II, and III, which hang from thick braided ropes, pool and sag; these works evidence a similar entropy and tension between form and formlessness as Robert Morris’s felt pieces from the mid- and later 1960s. One could even make the argument that her use of transparent color finds an echo in Larry Bell’s coated glass structures, on view in a nearby gallery at Dia Beacon. But the unprecious, everyday nature of Nengudi’s materials and the ephemerality of her sculptures (their shapes can just as easily be un-shaped) empty out the pomposity and macho posturing of those contemporaries, while adding a sense of playfulness to the conversation—Nengudi once described her art as akin to “a butterfly landing on one’s knee.” The narrow rectangular units of Water Composition (green/yellow) owe as much to freeze pops as anything, and the whole series relies on a palette that seems to originate in Kool-Aid flavors. In a 2013 interview, the artist laughingly remarked that she made them “until waterbeds came out—and then I said, Well, I can’t do that anymore. Water in plastic has gone commercial,” a measure of her insistence on working with stuff of negligible monetary value.

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition (green), 1969–70/2023. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Senga Nengudi.

In the mid-1990s, Nengudi, whose performance work has always involved ritual from across cultures, began making dinner plate–size sand paintings in her studio, inspired by their use in Navajo, South Asian, and Tibetan Buddhist traditions to ward off harm, promote healing, or cleanse. Sandmining B expands this meditative practice into the space of installation. An expanse of sand, mounded here and there like breasts, is colored in spots with pigments (blue, green, orange, yellow) and pocked with footprints, out of which grow curving metal forms (discarded car parts); a twisted muffler adorned with stuffed pantyhose bulbs is propped against a wall smeared with colored powders. The effect is somewhere between ancient rite and the surface of an alien planet. From ceiling-mounted speakers, we hear Nengudi’s voice. She invokes ancestors who have suffered the worst kinds of violence and indignities and calls upon the viewer to honor them: “It’s time to gather our collective wits about us, chant the same song, hum the same melody of now, in force, en masse.” After these lines, musical improvisations by the late Butch Morris, one of the artist’s collaborators from her days at JAM, and Nengudi’s son, Sanza Pyatt Fitz, play on.

Senga Nengudi, Sandmining B, 2020. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Senga Nengudi.

It’s impossible not to think of Smithson here, not only for his Spiral Jetty, snaking out from the shore of the Great Salt Lake, with its manipulation of dirt and evocation of Native American earthworks, but also his Mirror Displacements, for which he brought sand, gravel, and coral into the gallery, piling it against sleek mirrors. But whatever the shared language between Smithson and Nengudi, or between Nengudi and any of the other artists in Dia Beacon’s collection, there is a crucial difference: Nengudi says the quiet part out loud, whether it’s her engagement with Indigenous and transcultural practices, her embrace of non-art materials, her fascination with ritual and spirituality or with ancestors and history. Nengudi’s practice is both fully at ease and entirely unexpected in its new home on the Hudson, and, with any luck, it will discomfit all that work around it, too.

Aruna D’Souza is the 2022–23 W. W. Corcoran Professor of Social Engagement at the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, DC and a contributor to the New York Times and 4Columns. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.