Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The specters of history and photography haunt thirty-two works in the artist’s first US survey in over twenty years.

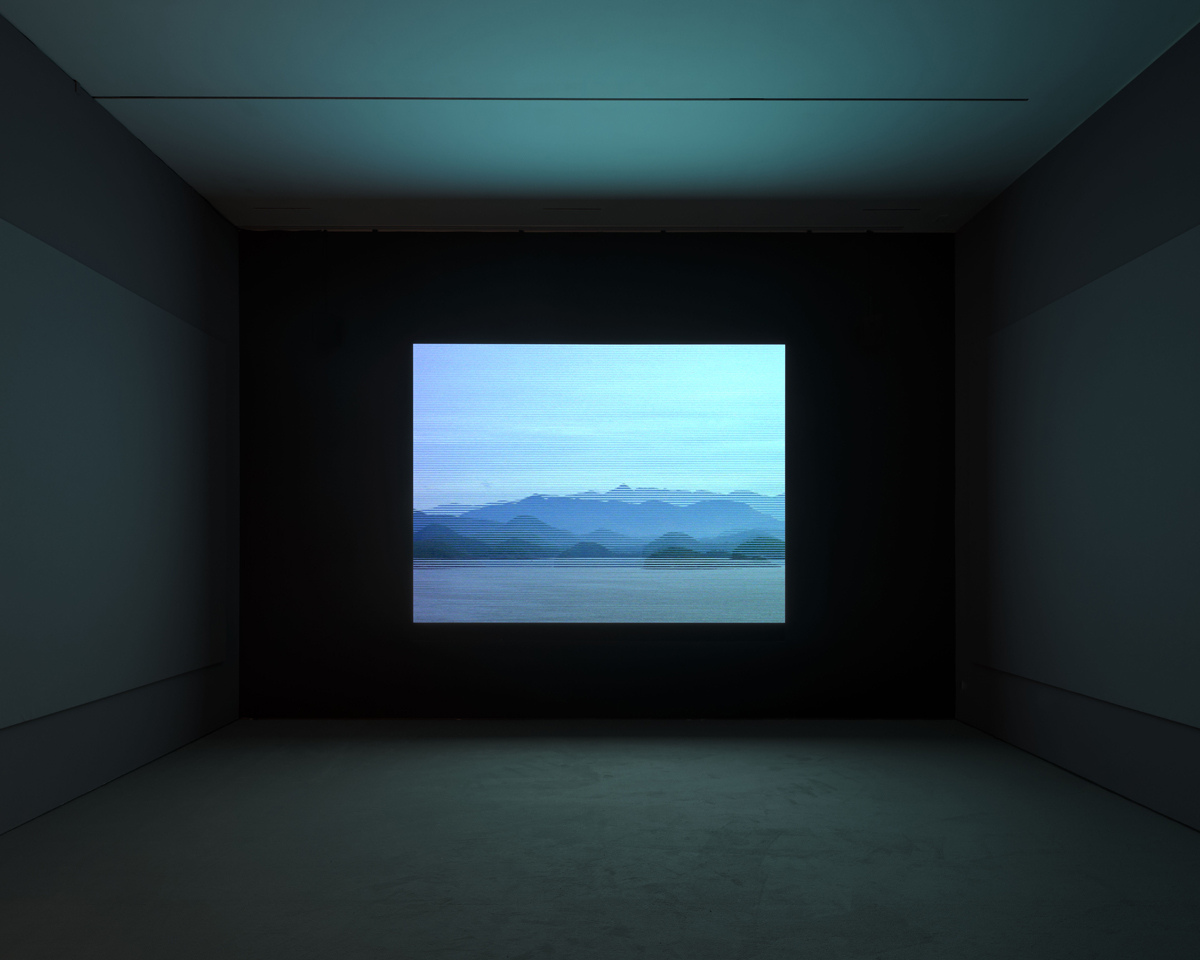

Stan Douglas: Ghostlight, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

Stan Douglas: Ghostlight, curated by Lauren Cornell, Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York,

through November 30, 2025

• • •

Édouard Manet never aspired to make history painting. But he was moved to embark on one in 1867—the year the young Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, whom France’s Napoleon III had installed as Emperor of Mexico in 1864, was executed. Outraged over Napoleon III’s abandonment of his puppet, Manet tried to capture the latter’s death by firing squad over the course of the next two years, making version after version as a relentless stream of often conflicting news stories, illustrations, and—most importantly—photographs emerged. He ended up cutting one of them to pieces out of frustration. The problem, it seemed, had to do with photography per se: this new form of reportage had not, technologically speaking, caught up to the speed of life. The snapshot was not yet possible, so photographers deployed collage, reenactment, and reconstruction to record events—strategies not immediate enough to satisfy Manet’s aspiration to make sense of modern times.

Stan Douglas, Ghostlight, 2024. Inkjet print mounted on Dibond aluminum, 48 1/8 × 120 inches. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner. © Stan Douglas.

This is the story that has been playing on repeat in my mind as I consider Stan Douglas: Ghostlight, at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College, his first US survey in over twenty years. (Part two, Metronome, featuring a significantly different checklist, is taking place at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, MO, through October 11.) The title refers to the exhibition’s opening image, a lone stage light in a darkened theater, kept on, according to showbiz tradition, for both safety reasons and for the ghosts who come out to perform once everyone goes home. And indeed, as evidenced by the thirty-two large-scale photos, video, film, and cameraless prints on view at the Hessel, Douglas’s work is full of specters of history, but also the past lives of the photographic medium itself.

Stan Douglas: Ghostlight, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured: Hors-champs, 1992.

Where Manet, back then, was laid low by photography because it couldn’t yet capture the immediacy of history, Douglas questions its trustworthiness precisely because he doubts that history is immediate at all. How can photography document something that is never punctual, never agreed upon, never even recognized as such until all that remains are traces? Douglas’s solution is to seize upon events whose meanings are inherently unstable—he has described them as “moments when history could have gone one way or another.” Perhaps that is why he reverts to early photography’s techniques, the ones that frustrated Manet so much.

Stan Douglas: Ghostlight, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon.

Sometimes the event itself is not even visualized, but is present as a haunting, as with Hogan’s Alley (2014), which bears witness to the demolition of a Black neighborhood in the artist’s hometown of Vancouver that was once the site of an important jazz scene. The five-by-ten-foot picture is immersive, almost cinematic, and offers a bird’s-eye view of the moonlit cityscape. The image is a composite, stitched together from many individual pictures of what was essentially a digital stage set, a reimagining of the original site via oral histories, news reports, old photographs, and the like. Where information didn’t exist, Douglas has interpolated it—a necessary deployment of what Saidiya Hartman has called “critical fabulation” to deal with the silences of archives when it comes to the lives of Black folks. The painstaking realism here is the tip-off that this scene is not “real” in the limited terms of contemporary documentary photography, of course—we can see too much, with too much clarity and sharpness, for a single lens to have caught the scene.

Stan Douglas, Disco Angola: Exodus, 1975, 2012. Digital chromogenic print mounted on aluminum, 71 × 101 1/2 inches. Courtesy Glenstone Museum.

By setting out to make photographs of events that have already happened—even if, as Douglas says, we are still living in the residue of those happenings—the artist leaves open the possibility for a form of time travel in his work, a smushing together of past, present, and future, of local and global, in ways that insist on aligning the mundane and the big-H Historical. The series 2011 ≠ 1848, which he showed at the Canadian pavilion for the 2022 Venice Biennale, is one example: reconstructions of an Arab Spring action in Tunis and an Occupy Wall Street protest in New York join an image of rioting fans after the Vancouver Canucks lost a game in the Stanley Cup finals. (My one complaint in this otherwise excellent show is that not enough of Douglas’s photo series are shown in their entirety, which dilutes their effect.) By linking these incidents, he’s not arguing that they are necessarily related, or that they are the unfinished business of the mid-nineteenth-century pan-European workers’ uprisings alluded to in the title of the suite. Nor is he making a pat historical argument that the New York dance scene of the 1970s had anything to do with the decolonization of Angola (Disco Angola, 2012), or that a 1912 labor gathering in Vancouver shares DNA with the crowds at a horse race in 1955 and a hippie “smoke-in” in 1971 (Crowds and Riots, 2008). But he’s not not saying any of these things, either. His understanding of history is infinitely porous, full of doubts and possibilities and what-ifs, and his formal methods both produce and account for that.

Stan Douglas: Ghostlight, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured: Nu•tka•, 1996.

If Douglas’s recasting of photography relies on composite strategies (collage, layering, suturing), his film and video work often involves splitting (Hors-Champs, 1992), doubling (Der Sandmann, 1995), and looping (Luanda-Kinshasa, 2013). Nu•tka• (1996) shows present-day Vancouver Island, the unceded territory of the Mowachaht-Muchalaht First Nations. The single image is split into two separate feeds that display at different rates, so that the screen vibrates and pixelates, becoming more or less unreadable. The soundtrack, meanwhile, is doubled: two narrators—one purporting to be the Spanish explorer José Estéban Martinez, the other the English naval captain James Colnett—speak over and at odds with one another, which makes sense, given they were colonizers fighting over land that was not theirs. The film is accompanied by a suite of photos of the island, each of which points out in subtle ways that it was never a terra nullius.

Stan Douglas: Ghostlight, installation view. Courtesy Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College. Photo: Olympia Shannon. Pictured: Birth of a Nation, 2025.

And then there’s Birth of a Nation (2025), shown here for the first time. It focuses on the infamous “Gus chase” from D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film, in which Gus, a Black freedman and army captain (played by a white actor in blackface), proposes marriage to Flora, a white woman, who, in her horror at being so besmirched, flings herself off a cliff. Flora’s brother Ben, a Klansman, chases Gus down and, with his racist coconspirators, lynches him. One of the five channels of Douglas’s installation shows Griffith’s original sequence; on either side and below are four other projections, breathtaking in their apparent visual fidelity to the original, although departing at crucial points from its narrative. Douglas pries apart Griffith’s film, dedicating a channel to Flora, her brother, and—because Gus’s point of view is never accounted for by Griffith—two new characters, Sam and Tom. The demeanors of the latter make clear that “Gus” was only ever a projection of Flora and Ben’s white, racist imaginations. (Sam is shown walking through the forest, minding his own business, for pretty much the whole thirteen-minute sequence.) Griffith used realist filmmaking techniques—innovative editing, relatively unaffected acting styles, and shooting outdoors—to naturalize his anti-Black propaganda. Douglas aims for the opposite, an unraveling of the ways in which filmmaking serves ideology by papering over the psychic miasma lurking beneath its seamless appearance. By the time we reach the end—when, suddenly, one screen switches from black-and-white to color, and we see Tom’s body hanging not from a tree but from a crane in a blue-screen studio, with cast and crew gathered around—photography’s evidentiary claim is revealed for what it is: a construction, a fiction, a trap.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times and 4Columns. Her new book, Imperfect Solidarities, was published by Floating Opera Press last summer.