Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

The Metropolitan Museum offers a global history of the art movement.

Surrealism Beyond Borders, installation view. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Surrealism Beyond Borders, curated by Stephanie D’Alessandro, Matthew Gale, Sean O’Hanlan, and Carine Harmand, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through January 30, 2022

• • •

Clocking in at more than 275 paintings, sculptures, works on paper, photographs, films, and audio recordings from more than forty-five countries, spanning eight decades, and installed in fourteen galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Surrealism Beyond Borders is sprawling, no question. But this is as much a function of conception as of size. The curators of the show—a team led by Stephanie D’Alessandro of the Met and Matthew Gale of the Tate Modern, where the show will travel after its New York run—set a mammoth task for themselves: to map how the artistic movement, officially born in Paris in the 1920s, was embraced and theorized globally, offering artists a language of political resistance and defiance of convention rooted in explorations of the unconscious and the antirational.

To survey the movement without centering the role of the French Surrealists, especially that of André Breton, facetiously dubbed the “Pope” of the group for his predilection for anointing and excommunicating members at will, the curators have turned to what they call a “rhizomatic” model of thinking. It’s a useful approach, not least because it allows them to dispense with nation-bound narratives as well as stifling assumptions about periodization and belatedness, in which artists in, say, Brazil or Egypt are understood to simply be latecomers to ideas that Europeans had already worked through—and moved on from—years or even decades ago. It also offers a new way of defining Surrealism itself: as the ideas of Breton and his comrades circulated, they propagated new formulations of what Surrealism was and what it could achieve, especially for artists resisting colonialism, repressive religious and cultural orthodoxies, nationalisms, racism and antiblackness, gender inequality, and other forms of persecution.

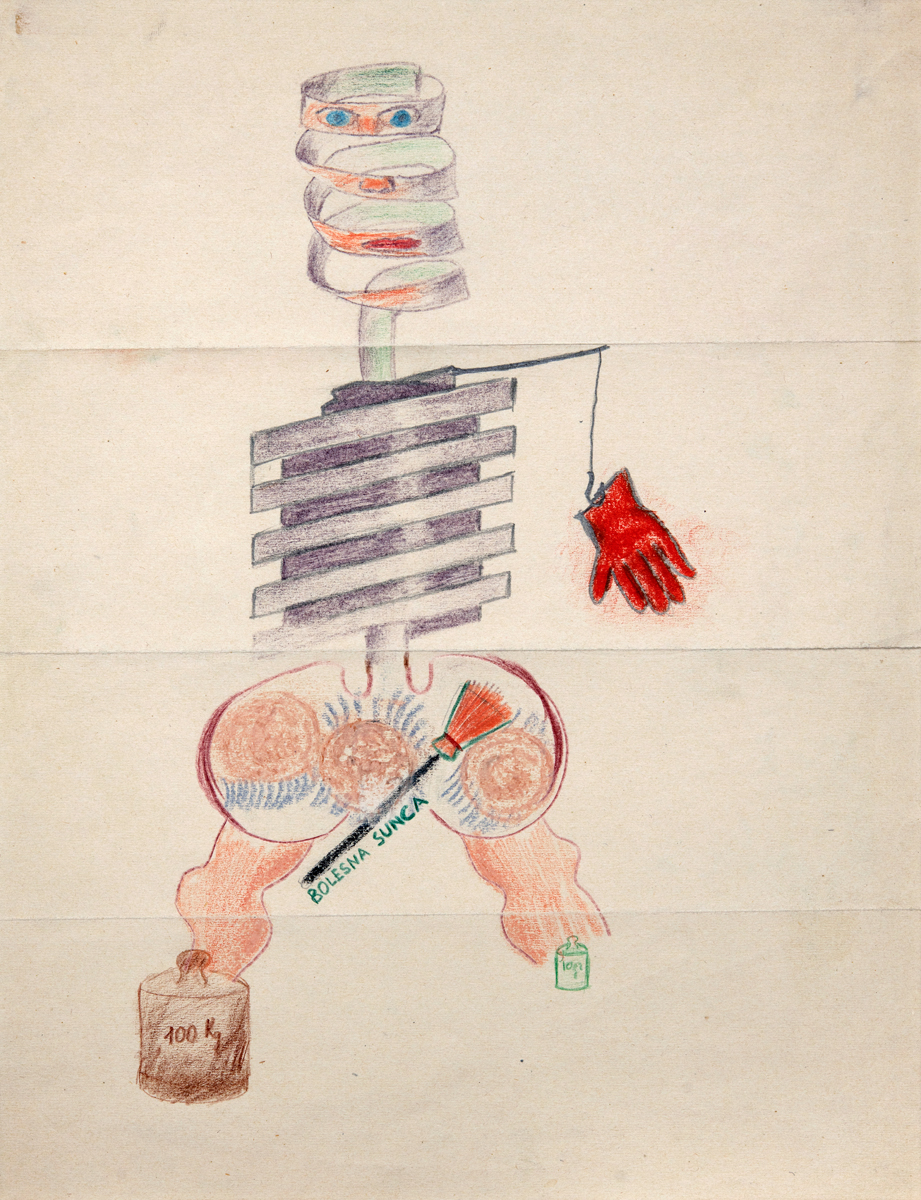

Aleksandar Vučo, Lula Vučo, Vane Živadinović Bor, Le cadavre exquis, no. 11 (The Exquisite Corpse, no. 11), 1930. Pencil, colored pencil, and ink on paper, 12 3/8 × 9 7/16 inches. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade.

The first room of the show is filled with—to my mind—one of the most deadly boring art forms of the twentieth century, the cadavre exquis, or exquisite corpse drawing. Yes, it effectively introduces the idea of collective creation and the operations of chance that result when each artist adds to a drawing without knowing what came before. But it’s always struck me as very much “you had to be there” in terms of aesthetic value, like when a friend describes what a blast they had at a drunken party you didn’t attend. It’s not the drawings on view that are interesting so much as the way they function as records of meetups, now in Paris, now in Belgrade, now in Mexico City, now in Lisbon, each creating a new connective thread among Surrealists around the globe. (Elsewhere, voluminous displays of magazines and other printed matter from geographically distant places, often with contributions by far-flung comrades, makes a similar point.)

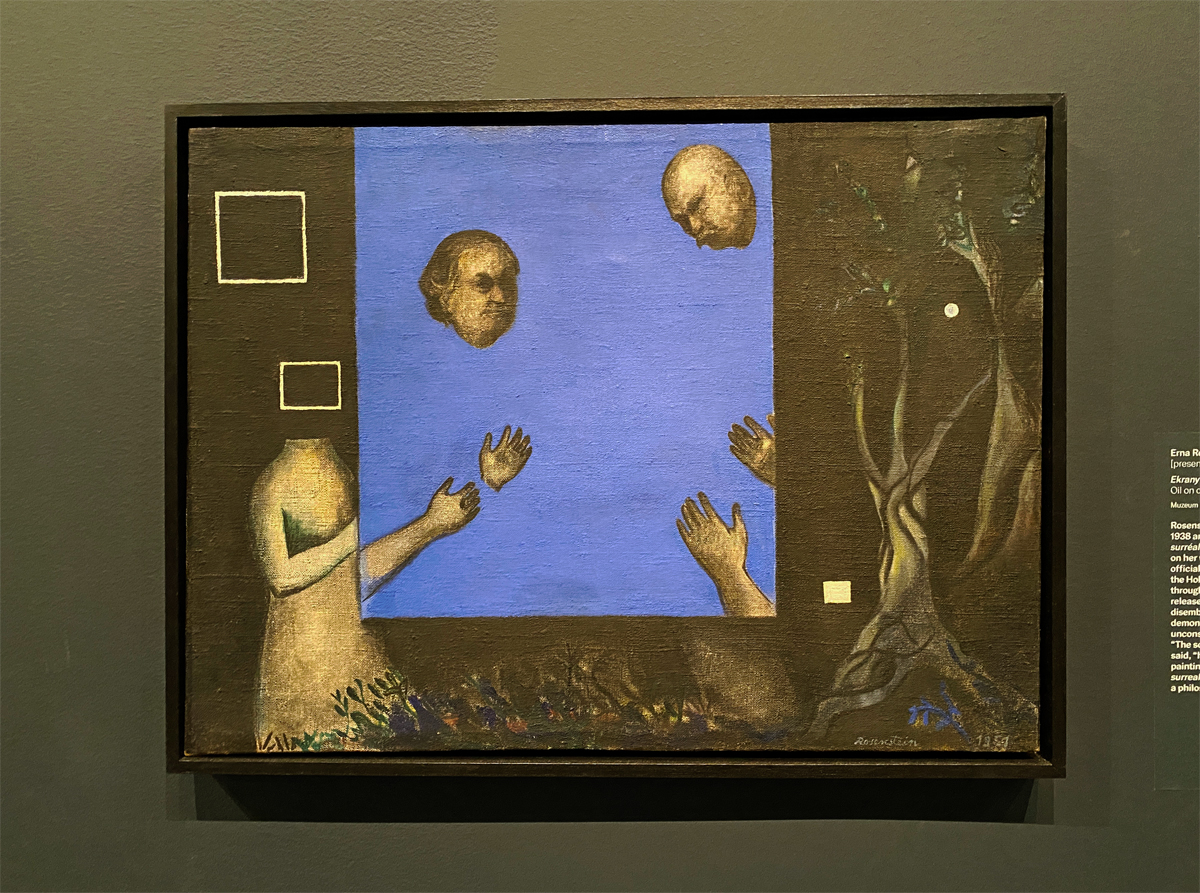

Erna Rosenstein, Ekrany (Screens), 1951. Installation view. Photo: Aruna D’Souza.

While Parisian Surrealism certainly had a political program—the turn to the dark, unknown, chaotic, and untamable aspects of human nature at a moment when the dehumanizing efficiencies of industry, war, and colonialism were being celebrated in Europe was no doubt political—the work of canonical, Western European and American Surrealists ends up feeling tame and even twee when placed in a global context. The exploration of dreams motivated Max Ernst to create his relief sculpture Deux enfants sont menacés par un rossignol (Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, 1924), an early work of French Surrealist art (Ernst himself was German, living in Paris at the time). It also prompted the American Dorothea Tanning to produce Eine kleine nachtmusik (A Little Night Music, 1943). But it was the all-too-real encounter with an actual nightmare that led Polish artist Erna Rosenstein to paint Ekrany (Screens) in 1951, one of the most arresting works in the show. The image features two heads that float on a deep-blue background, having disengaged from their bodies: the canvas is Rosenstein’s attempt to confront the trauma of the murder of her parents during the Holocaust.

Koga Harue, Umi (The Sea), 1929. Oil on canvas, 51 3/16 × 64 inches. Courtesy the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

It is illuminating to see how ostensibly self-evident concepts, such as “the irrational,” could be translated in so many ways. In Belgium, René Magritte was making works like La durée poignardée (Time Transfixed, 1938), his iconic painting of a steam train chugging out of a fireplace. In Japan, Koga Harue’s Umi (The Sea, 1929), depicting an oversized bathing suit–clad woman surrounded by technical notations and out-of-scale commodities, was a foray into “Scientific Surrealism,” which sought to push back against his country’s notions of progress. And in Iran, Kaveh Golestan’s series of tiny photographs, Az div o dad (Of Demon and Beast, 1976), made by passing historical images and other objects in front of an open camera shutter, proposed monstrous versions of Qajar rulers just a few years before revolutionaries deposed the Shah.

One of the contradictions that surfaces in Surrealism Beyond Borders is the way French Surrealists often sought the uncanny and the irrational via the racist concept of “the primitive” at the same time as artists from, say, Africa, Oceania, Asia, South America, and the Caribbean readily deployed Surrealist concepts to assert their anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist, and anti-racist expressions. For Aimé Césaire, whose encounter with the French cadre was a step along his path to the theorization of Négritude, Surrealism was most valuable as a tool of “disalienation” that allowed him to turn his gaze toward Africa; Léopold Senghor, another founder of the Négritude movement, conveyed something similar when he said, “We accepted Surrealism as a means, but not as an end, as an ally, and not as a master.”

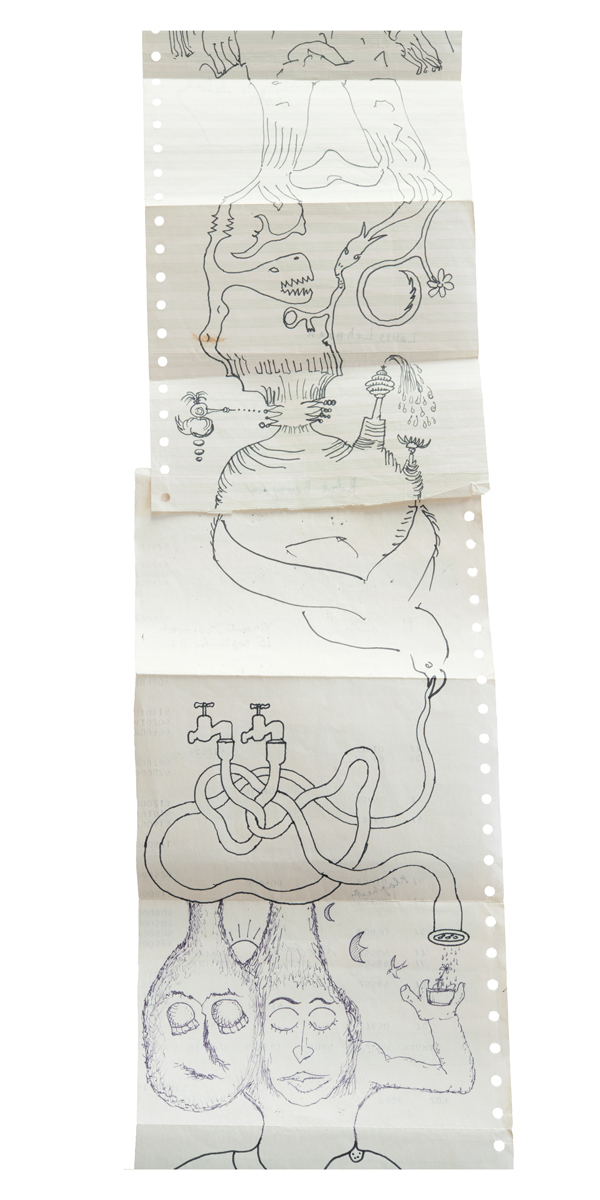

Ted Joans, Long Distance, 1976–2005. Ink and collage on perforated computer paper, dimensions variable. © Ted Joans estate. Courtesy Laura Corsiglia. Photo: Joseph Wilhelm / Meridian Fine Art.

Indeed, the way Black artists—in the Caribbean, in the US, in Africa—mined Breton’s aesthetic notions is one of the most fascinating aspects of the show, especially in the case of Ted Joans. The African American jazz poet, trumpeter, and painter discovered the movement when he was a boy thanks to the copies of Minotaure (a Surrealist magazine published in Paris in the 1930s) that his aunt would bring back from her white employers living in Cairo, Illinois. He melded the ideas he found in its pages with many others to advance his goals, which were bigger than Breton, bigger than Surrealism, bigger than art: “I am Maldoror, Malcolm X, the Marquis de Sade, Breton, Lumumba,” he wrote. “They are my fuel, my endurance, and I will continue to use all the means to win my freedom, which will become freedom for all. Black Power is a means to achieve this freedom.” Among his paintings, drawings, altered photographs, and books is the show’s most compelling cadavre exquis: Long Distance (1976–2005), made of old-school perforated computer paper. Joans would take the drawing with him on his music tours, or mail it to people he had met on his travels, so they could add to it; though he died in 2003, the piece continued to circulate, with further additions, for two years—a poignant reminder that the project was bigger than one man.

Ted Joans, Long Distance (detail), 1976–2005. Ink and collage on perforated computer paper, dimensions variable. © Ted Joans estate. Courtesy Laura Corsiglia. Photo: Joseph Wilhelm / Meridian Fine Art.

There are many more things to say about the show, not all of them laudatory: the too-packed ephemera cases; the overabundant wall text (some of which, frustratingly, points to the existence of work that isn’t in the show, such as that of a Surrealist circle in Aleppo in the 1940s); the fact that the single artist working in South Asia is a wealthy descendent of colonizers taking erotic photos of teenage Ceylonese boys. (Seriously, there are not that many ways to out-creep Hans Bellmer, whose polymorphically perverse pictures are hung nearby, but Lionel Wendt manages to do so.) In the end, perhaps the greatest value of Surrealism Beyond Borders will be much like the value of Breton’s Surrealism itself: this curatorial proposition is an entrée, and a very rich one, from which future thinking and making will emerge.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. She co-curated the 2021 exhibition Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And at the Brooklyn Museum of Art and is the editor of a forthcoming collection of the writings of Linda Nochlin, Making It Modern (Thames and Hudson, 2022). She is also a contributor to the New York Times. She was awarded the Rabkin Prize for arts journalism in 2021.