Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

A series of one-year performances demonstrate the merging of

art time and life time.

Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999, installation view. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio. © Tehching Hsieh. Pictured: One Year Performance 1978–1979 (Cage Piece), 1978–79.

Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999, curated by Humberto Moro and Adrian Heathfield, with Liv Cuniberti, Dia Beacon, 3 Beekman Street, Beacon, New York, on long-term view

• • •

If Tehching Hsieh didn’t exist, we would have to make him up. The novelist Lisa Hsiao Chen recently posted on Instagram a list of books in which the Taiwanese conceptual-slash-performance artist appears as a character, sometimes under his own name, sometimes lightly disguised: Rachel Kushner’s The Flame Throwers, Molly Prentiss’s Tuesday Nights in 1980, Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs, Morgan Võ’s The Selkie, Lisa Ko’s Memory Piece, and, of course, her own spare but sublime account of how time structures a life, Activities of Daily Living.

Tehching Hsieh, performance view of One Year Performance 1980–1981 (Time Clock Piece), artist’s studio at 111 Hudson Street, 1980–81. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Michael Shen. © Tehching Hsieh.

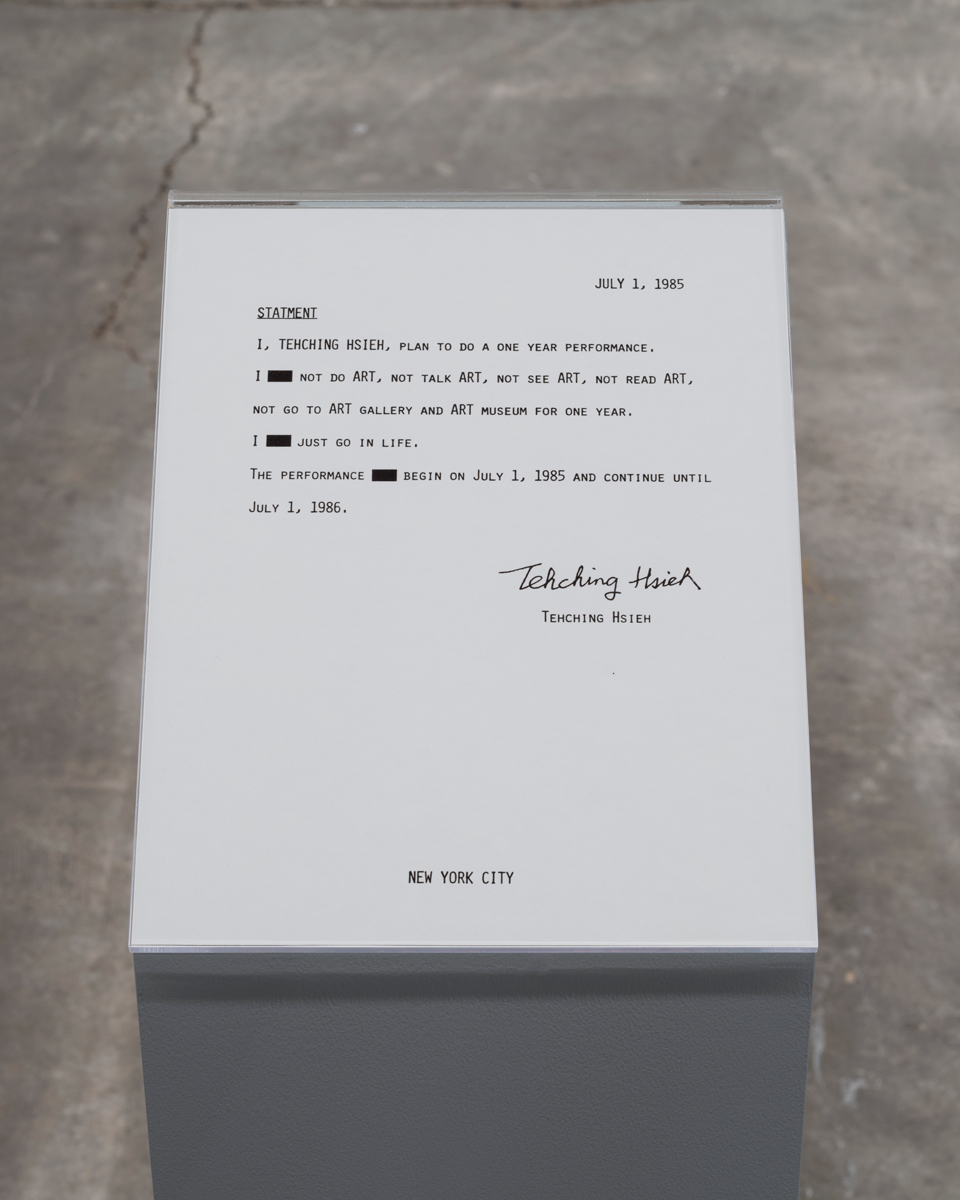

Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999 at Dia Beacon—the artist’s first major exhibition in the US, focusing on six of his longue-durée performances, each installed in its own gallery on the lower level of the museum—offers ample explanation for why he has been such an object of fascination. Hsieh—who literally jumped ship in Delaware and arrived in New York in 1974 without papers—began a series in 1978 that he called One Year Performances. All involved some form of deprivation: locking himself in a cage with no mediation with the outside world (Cage Piece, 1978–79); punching a time clock on the hour, 24/7/365, which meant he could only leave his apartment for fifty-nine minutes at a time and never get a full night’s sleep (Time Clock Piece, 1980–81); living outdoors in Manhattan, with just a sleeping bag allowed for shelter (Outdoor Piece, 1981–82); tying himself with an eight-foot-long rope to another performance artist, Linda Montano (Art/Life, also called Rope Piece, 1983–84); refusing to make, see, read, or talk about art (No Art Piece, 1985–86).

Tehching Hsieh, performance view of One Year Performance 1981–1982 (Outdoor Piece), New York, 1981–82. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Tehching Hsieh. © Tehching Hsieh.

These projects place Hsieh firmly into the context of early 1970s bodily oriented practices—think Chris Burden shooting himself, Vito Acconci masturbating under the false floor of a gallery for hours a day, Marina Abramović and Ulay standing with their hair knotted together until they collapsed from exhaustion. What distinguishes him, however—and here is where I think the fascination arises—is that Hsieh eschewed spectacle almost entirely, and in doing so came to occupy a rarefied space of pure artistic obsession. Instead of making his work in public, he largely relied on showing it after the fact via systematic documentation, which he treated as evidentiary; some of his projects, including the legendary Art/Life, have never been seen in exhibition until now.

Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999, installation view. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio. © Tehching Hsieh. Pictured: One Year Performance 1985–1986 (No Art Piece), 1985–86 (detail).

Hsieh’s One Year Performances all started with a statement, written in the language of a contract, defining the parameters of the piece. He would create a calendar, with dates circled to indicate when people could come to see him perform (usually in his Hudson Street loft, once or twice a month). He set up various legalistic apparatuses to assure any future audience of the veracity and authenticity of his endeavors—for Cage Piece, a lawyer’s statement attests that the signed paper seal placed around the door of the wooden cell was still intact after 365 days; for Time Clock Piece, another witness statement confirms that the signed time cards Hsieh accumulated were real and untampered with. For Art/Life, a colleague affixed a lead seal inscribed with his signature to the rope to ensure it couldn’t surreptitiously be removed by either party.

Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999, installation view. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio. © Tehching Hsieh. Pictured: One Year Performance 1978–1979 (Cage Piece), 1978–79 (detail).

No Art and Tehching Hsieh 1986–1999 (Thirteen Year Plan)—the latter involved making work for the period in question that would never be seen by anyone—are documented differently: the curators have placed the statements of intention and calendars with no dates circled in otherwise empty galleries.

Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999, installation view. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio. © Tehching Hsieh. Pictured: Tehching Hsieh 1986–1999 (Thirteen Year Plan), 1986–99.

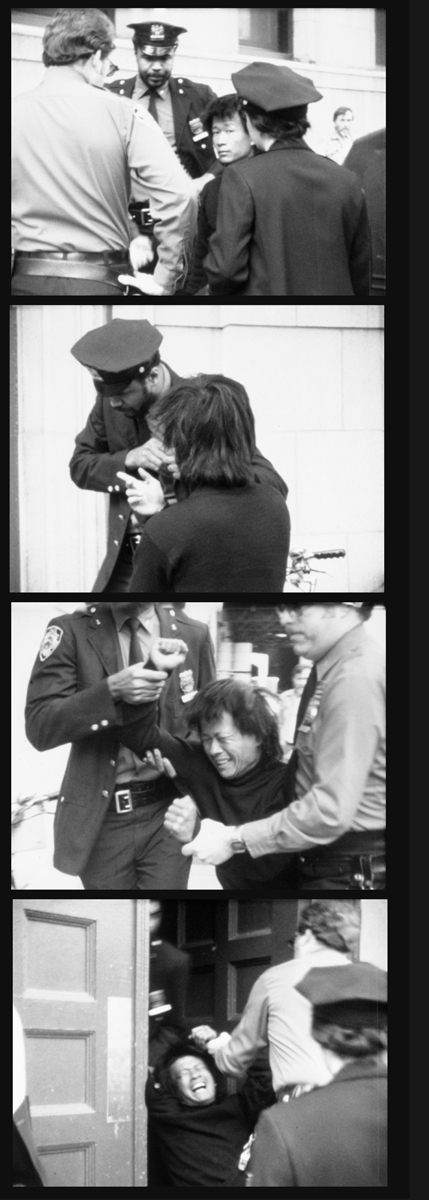

And then there are the more indexical forms of recording. These include the identically shot photographs of his year doing Cage Piece, in which the indication of time passing takes the form of his ever-growing hair, and the prisoner’s countdown of days rudely incised into the cage’s wall (which is reconstructed in the gallery). For Time Clock Piece, we find color pictures of him punching in, a film comprised of single-frame shots of him doing so—a year edited into just six minutes fifty-five seconds—and the time cards themselves. Photographs taken by him and his friends of his days living rough in the city—sleeping, bathing, defecating, and so on—stand in for Outdoor Piece, alongside photocopied maps for each day, red pen notating the different locations he carried out such activities.

Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano, performance view of Art/Life One Year Performance 1983–1984 (Rope Piece), New York, 1983–84. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano, Life Images. © Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano.

The photos that Hsieh and Montano took as part of Art/Life are particularly captivating—how could they not be? They go some way to answer lingering questions about how it was possible for two people to remain together for so long: there are pictures of the beds that Hsieh designed and built, close but not too close, and plenty of shots of them lying around, bored. Others show them walking Montano’s dog on a leash or seeing a group of toddlers fastened together with a cord being taken by their teachers to a park—rope pieces in the wild. There are photos of Hsieh undertaking paid carpentry work, while Montano stands quietly below his ladder. And yet, despite this generous documentation, there is a silence, too—the cassette tapes they made of their daily conversations were sealed shut, never to be heard by anyone. Hsieh and Montano have more or less refused to speak about the experience publicly in the forty years since it was made; they broke that reserve during a panel on the opening day of the exhibition, but much remained unsaid. All this evidence only goes so far: we can see what that time looked like, that is to say, but we can never hear what it sounded like, or, even more, feel what it felt like.

Tehching Hsieh: Lifeworks 1978–1999, installation view. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio. © Tehching Hsieh. Pictured: Art/Life One Year Performance 1983–1984 (Rope Piece), 1983–84.

In an essay from 1986, Marcia Tucker wrote about a friend who took issue with the ethics of Hsieh’s work: “He seemed to be making a mockery of the homeless, the incarcerated, those forced to work at jobs which were meaningless to them,” the friend said. Tucker countered that Hsieh’s is “a moral statement about those very issues through extremes of self-discipline, physical hardship, endurance, and danger.”

Tehching Hsieh, performance view of One Year Performance 1981–1982 (Outdoor Piece), New York, 1981–82. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. Photo: Claire Fergusson. © Tehching Hsieh.

Of course, it is neither. Hsieh was forever chasing the idea that art time and life time should be coextensive, and he was an undocumented immigrant: the experiences he cultivated were not abstract premises but real risks. In 1978, he did a piece (not in the Dia show) called Wanted by U.S. Immigration Service, a poster complete with photo, biometrics, and fingerprints. It was spurred, he said, by the depression brought on by living underground, in constant fear of detention, unable to make art. In 1982, while he was surviving on the streets for Outdoor Piece, he took part in a show, contributing the following statement: “I shall publish my WANTED poster in the exhibition ILLEGAL AMERICA at Franklin Furnace in New York. If someone should see me, please call the Immigration Service at 212-349-8735.” He was in fact arrested (but not deported) on March 3, 1982, during the course of Outdoor Piece and while Illegal America was on view, not because someone who saw his declaration at Franklin Furnace decided to take him up on the challenge—rather, he was charged with assault with a blunt object for defending himself in an altercation. You can see the arrest record in the documentation of Outdoor Piece at Dia—art and life merging, in the best and worst possible ways.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer and critic based in New York. She contributes to the New York Times, 4Columns, and Hyperallergic. Her new book, Imperfect Solidarities, was published by Floating Opera Press in 2024.