Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

At Olana, an artist takes on colonialism and Frederic Church.

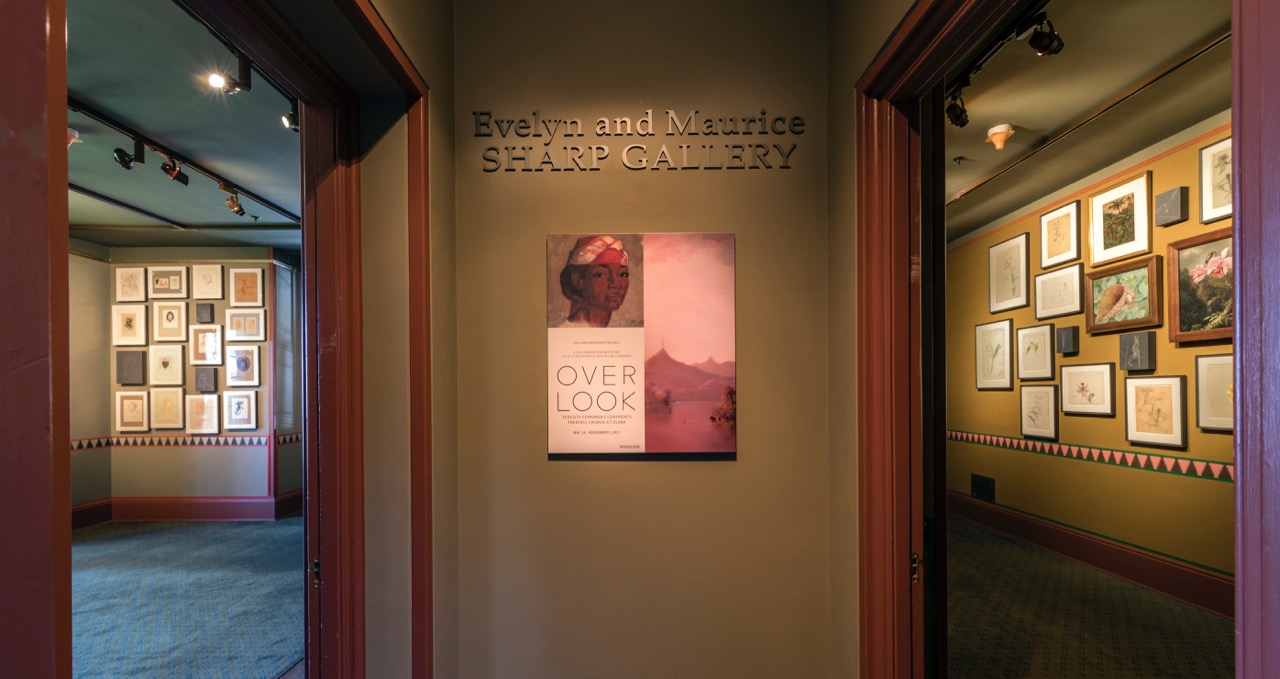

Evelyn and Maurice Sharp Gallery, Main House, Olana. © Peter Aaron/OTTO.

Overlook: Teresita Fernández confronts Frederic Church at Olana, Evelyn and Maurice Sharp Gallery, Olana State Historic Site, Hudson, New York, through November 5, 2017

• • •

To see Teresita Fernández’s installation, Overlook, one must book a tour of Olana, the house built by the preeminent Hudson River School landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) in the last half of the nineteenth century. Perched atop a rise in a 250-acre landscape with sweeping views of the Hudson River, the Arabesque confection is filled to the brim with Chinese tiles, Indian woodwork, Middle Eastern carpets, Persian ceramics, Mexican sombreros and folk art, pre-Columbian artifacts, and old master and nineteenth-century paintings, all picked up during the painter’s trips to Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East or at dealers in New York City. Only after wending your way through this decor—a sort of architectural self-portrait of Church as intrepid artist-explorer and inveterate shopper—is Fernández’s quiet, elegant, and devastatingly effective intervention visible.

Beth Schneck Photography, Southern View Panorama from Olana, 2013. Image courtesy bschneckphoto.com.

Overlook is installed in two rooms on the second floor of the house. In the first room, two opposing walls are hung, Salon-style, with paintings, drawings, and prints: one consists entirely of landscapes, the other of portraits. In the second, smaller room is a similar setup, this time with botanical drawings and paintings on one side, and a single portrait on the other.

The landscapes all portray sites in South and Central America and the Caribbean, many of them places that Church visited in his quest to emulate the journeys of the early nineteenth-century naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. The painter garnered his fame back in the US by transforming his on-site sketches into some of the most popular and widely known canvases of the mid-nineteenth century. (His most famous work, Heart of the Andes, attracted more than 12,000 viewers, who each paid a quarter to see it when it was first shown in New York in 1859; it eventually sold for $10,000, a record for a living American artist at the time.) Fernández hangs Church’s drawings, watercolors, and oil studies cheek and jowl with those by other traveler-artists of his era, including the American Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904), the Englishman R.N. Captain Seymour (1802–87), and the Mexican José María Velasco (1840–1912). (The works are drawn entirely from both Church’s own stash, now in the collection of the Olana State Historic Site, and from the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, one of the most complete privately held collections of the art of the Americas and a collaborator on the project.)

Sitting Room of the Main House at Olana State Historic Site. Pictured: Martin Johnson Heade, Sunset: A Scene in Brazil, 1864–65, from Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. © Peter Aaron/OTTO.

Among these landscapes are interspersed six of Fernández’s own panels, all titled Nocturnal (Olana). Though their titles suggest they are night views of the estate, they trade the geographic specificity and scientific accuracy sought by the nineteenth-century works with which they are hung for something rather more elemental—quite literally so, as they are made of graphite, not in the refined and manufactured form of a pencil but in a rawer, more material sense. Their dark bas-relief alternates between lustrous, burnished horizontal stripes of varying widths (suggesting river, fields, horizon) and occasional masses of shards (denoting shore, hills, outcroppings).

On the opposite wall of portraits, all except Fernández’s six panels were done by the Frenchman Auguste Morisot (1857–1951) during his eight-month trip to the Amazon basin in 1886. Morisot’s monotypes, watercolors, drawings, and engravings represent indigenous people—people, notably, that rarely if ever appeared in Church’s sublime landscapes. In addition to their ethnicity and tribal identifications, most of the figures were named in Morisot’s sketchbooks; all of them have an air of individuality that is marked and touching. A few, including Popurito Paja-bo, a Guahibo Indian, are depicted in multiple works on this wall. Interspersed with these are tonal, graphite–on–graphite-ground portraits by Fernández of Nari Ward, Ana Mendieta, Wifredo Lam, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Janine Antoni, and Jesús Rafael Soto—contemporary artists from the very regions that Church and his nineteenth-century contemporaries recorded in their art.

Evelyn and Maurice Sharp Gallery, Main House, Olana. © Peter Aaron/OTTO.

Fernández is best known for her large public installations that play with viewers’ optical perceptions and sense of their bodies in space. In Overlook, she offers a more pointed phenomenological dilemma, one that brings questions of colonialism (and its corollary, “exploration”) into sharp relief. The conundrum: you cannot see both walls at once. Look at the landscapes, and you turn your back on its occupants; look at the people, and you turn your back on the world. Or, to put it another way: look at the landscape, and you are looking along with the crowd of faces behind you, transforming vision into a collective, even communal, experience; look at the faces, and you become part of the view, you are caught in their gaze, you are part of their land. The same kind of back and forth goes for the second, smaller room of the installation—if you focus on the wall of botanical drawings, watercolors, and oil paintings by Morisot, Marianne North (the only woman besides Fernández on view, 1830–90), the Dane Fritz Melbye (1826–69), and Fernández, you cannot see Morisot’s single sketch of Popurito on the wall behind you.

Overlook is the second of a new projects series that puts contemporary artists “in conversation” with Olana and its collection; Fernández characterizes her conversation with Church as a confrontation, made manifest by the “either/or” terms in which the viewer must experience the installation. Church’s views of the Americas were at once idealized and imaginary—not representing a single geographical vista so much as a vision of paradise—and hyper-specific, resulting from careful study of plants and animals native to the regions he was traveling in, although often put in proximity in inaccurate ways. (Not unlike, one might add, the tastefully juxtaposed tchotchkes and ornamental flourishes in his house.) In his search for the sublime, people played an insignificant role. Engaging the multiple meanings of overlook—it is at once a vista and an omission—Fernández powerfully populates Church’s world.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and The Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson, and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.