Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

A New Museum show shakes up the family tree.

Justin Vivian Bond, My Model | My Self, 2017. Opening night performance. Image courtesy New Museum.

Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon, New Museum, 235 Bowery, New York City, through January 21, 2018

• • •

A behemoth of a show, Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon features over 150 works in a range of media—painting, sculpture, craft, film and video, photography, performance, and genres that have yet to be named—by forty-plus artists “who explore gender beyond the binary,” as the New Museum bills it. Trigger is undeniably timely: what better moment to look closely at identity politics than now, when it is being blamed for everything from the resurgence of “PC culture” (by the right) to the Democratic Party’s failure to win November’s election (by the left)? But the exhibition also marks the fortieth anniversary of the New Museum, founded by Marcia Tucker in 1977 as a radical departure from museums-as-usual; it became known for courting controversy and generating heated debate by grappling with the contemporary in all its glory and decrepitude. The curatorial team, led by Johanna Burton, envisioned the show to continue in that spirit, joining a lineage of watershed New Museum exhibitions including Extended Sensibilities (1982), Difference (1984–85), Homo Video (1986–87), and Bad Girls (1994)—all of which focused on gender and queerness during a previous iteration of our endless American culture wars.

This, then, is Trigger’s heritage, good to keep in mind while looking at an exhibition in which history as a form of genealogies is troubled, transformed, disrupted, and even exploded. What happens to a genealogical mapping of history—history as a matter of forefathers and, on occasion, foremothers, of filiation and genetic inheritance—when we trace gender in more complex ways, intersecting with other forms of experience such as race, sexuality, disability, and so on? How do we narrate our individual and collective pasts as a kind of family tree when we are forced to rethink how families are formed and how they are reproduced? What models of conceiving the past are adequate for our present? These are the questions Trigger puts front and center.

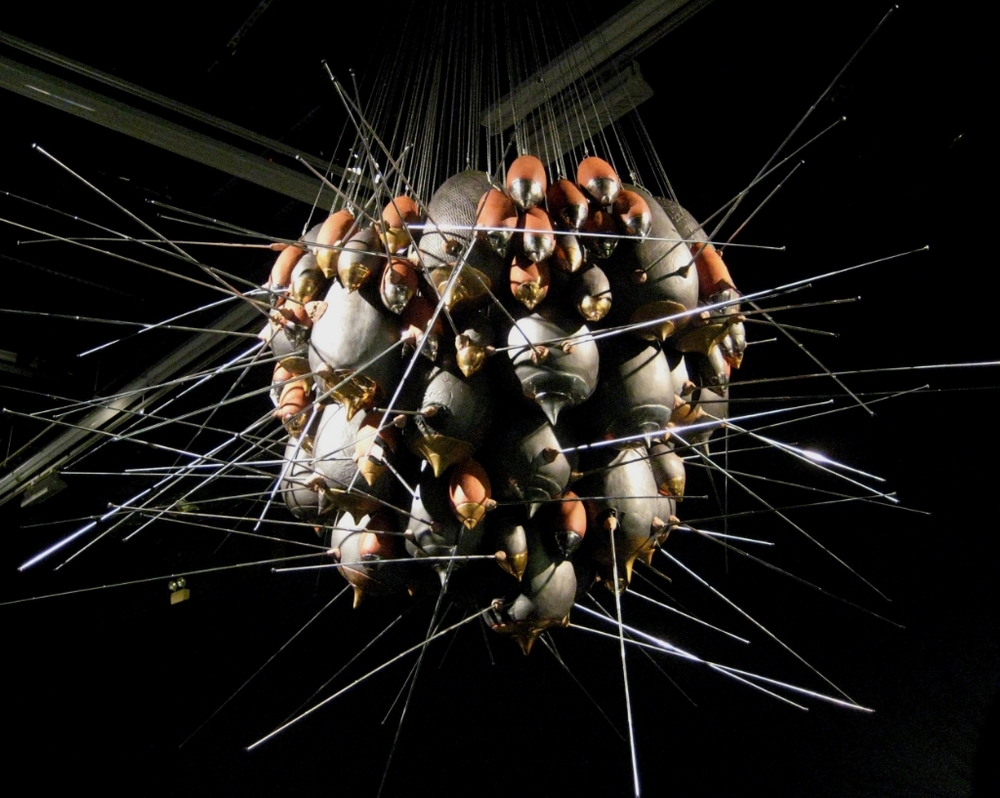

Simone Leigh, trophallaxis, 2008–12. Terra-cotta, TV antennae, gold, graphite, platinum, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

What use is a genealogical model of history, say, to deal with black femininity? Simone Leigh’s installation, Signs and Grips (2017), like much of her work, speaks to the violent interruptions of familial structures and circuits of knowledge caused by slavery, and the tenacity of black women in recovering and preserving those legacies. It consists of three discrete parts: a steel and raffia hut that echoes the women-built forms of African vernacular architecture; an untitled ceramic piece of a woman’s legs and torso bent into the wall, its pelvis replaced by an empty vessel tipped on its side, evoking black women’s role in the generation of families and culture while also raising the specter of their abuse by slaveholders, forced to bear children not their own; and a mass of terra-cotta and porcelain forms—sagging breasts, larval sacs, and alien pods all at once—bristling with metal antennae that hangs from the ceiling. The latter suggests other forms of reproduction, and introduces an element of Afrofuturism, where black history is imagined as only possible through a radical disruption of time, where seeing the past can only happen through the lens of what is to come.

Mariah Garnett, Encounters I May or May Not Have Had with Peter Berlin, 2010. Installation view, Human Resources, Los Angeles. Image courtesy the artist.

A number of works in the show approach the question of writing queer and trans histories (and art histories) by reviving lost legacies, finding other forms of filiation and connection, and even creating fictional ancestries. Among these is a video installation called Lost in the Music (2017) by Reina Gossett and Sasha Wortzel, which re-centers Marsha P. Johnson, a black trans activist and performance artist who threw the first stone—actually, a shot glass—at the Stonewall Inn uprising, a decisive moment in the history of struggle for gay liberation. Gossett and Wortzel’s film (like a number of works in the show, including Mariah Garnett’s Encounters I May or May Not Have Had with Peter Berlin, 2010, or Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz’s Toxic, 2012) relies on “docufiction” to tell its story: the actress Mya Taylor, shimmering with glitter, stands against a tinsel curtain that signals lushness and joy as much as the words coming out of her mouth—Johnson’s words—signal histories of violence, loss, and struggle in the face of the near erasure of the role of trans women of color in the gay rights movement.

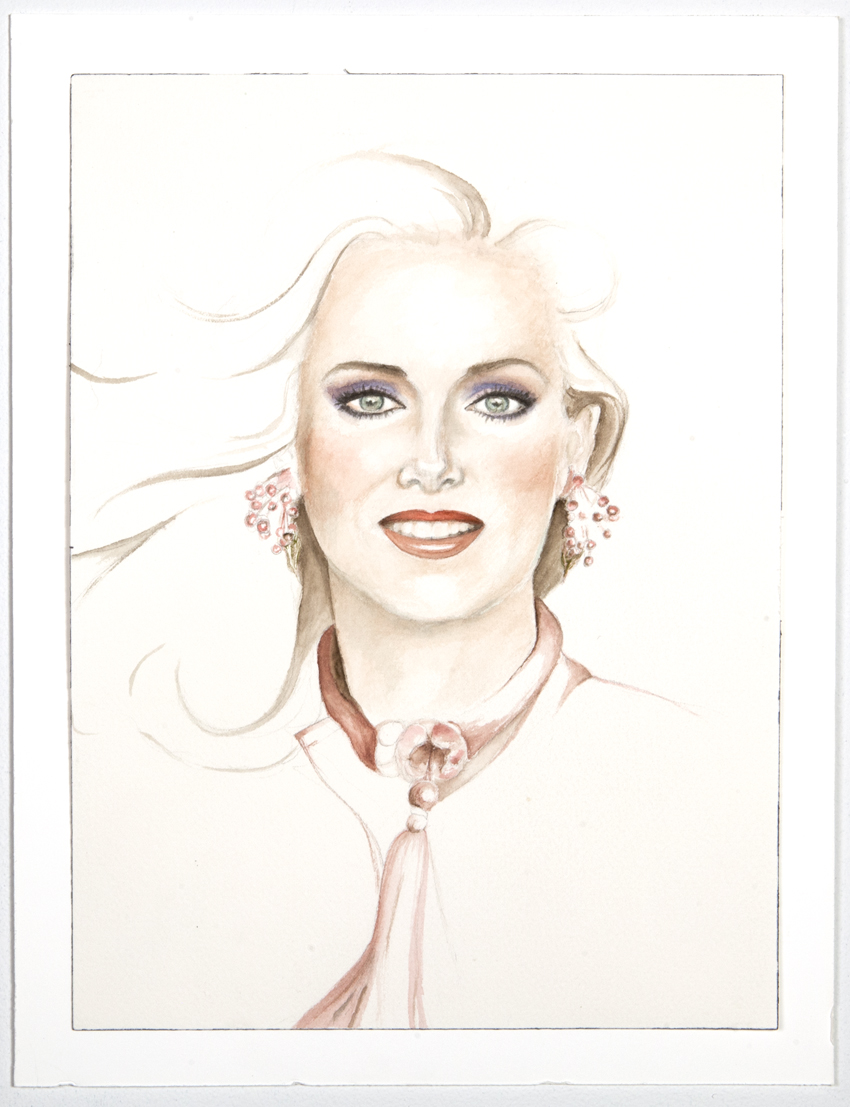

Justin Vivian Bond, My Barbie Coloring Book, 2014. Watercolor on archival paper, 14 ½ × 11 ½ inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Justin Vivian Bond’s deeply moving project, My Model | My Self, takes its title from a 1977 book by Nancy Friday, My Mother/My Self, which contended that (cis) womanhood was a process of acculturation—learning from one’s mother. A teenage Bond, who did not have a trans mother from whom to learn, instead chose a “mother” available to her from the world of advertising: Karen Graham, an Estée Lauder model who Bond once described “as blank and perfect as the sphinx—only more modern and wearing LOTS of make-up.” The installation is lined with paired watercolors of Graham and Bond-as-Graham, hung against custom-designed, commercially produced wallpaper; at its center are suburban-chic Louis XV-style chairs, a shag rug, a phonograph, and books. Here, identity is consumption, a form of capitalist fantasy, and why not? When our idea of family fails to accommodate a full range of identities and experiences, other models must be found.

There is a sense of joy, an almost utopian (or at least carnivalesque) energy emanating from this exhibition. Perhaps this is the upside of the curatorial decision to hang works cheek by jowl, but it also stems from the almost limitless possibilities of worlds unconstrained by traditionally defined identities, genealogies, affiliations, and histories. The creation of alternative genealogies can result in chosen families and unexpected forms of collectivity—as in the hilarious and canny activities of House of Ladosha, which span the worlds of fashion, rap, dance halls and balls, and the art world, and are conceived as a form of “sisterhooding,” or A.K. Burns and A.L. Steiner’s Community Action Center (2010–17), which uses queer erotic pleasure (in the form of a porn film) as a means of community building. New stories of the past necessarily result in new mappings of the present and new visions of the future: this is the stuff of political transformation. While Trigger errs on the side of offering too many prospective paths on this front, it is at the same time a vital reminder that identity politics, far from being a failure, as the right and left alike are quick to tell us, is alive, well, and getting on with changing the world.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and the Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson, and another book, Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts, will be published by Badlands Unlimited in spring 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.