Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

Sunken ships, stateless pavilions, and a purgatorial beach: this year’s biennale offers propositions for a time of crisis.

Overview of the Arsenale in Venice. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Venice Biennale 2019: May You Live in Interesting Times, Venice, Italy, through November 24, 2019

• • •

The Time Is Now

Ralph Rugoff, the curator of this year’s Venice Biennale, seems acutely aware that any major, international exhibition worth its salt must engage the question of art’s relation to our moment of crisis—when climate change, racism, massive human migration, nationalisms, the breakup of old political alliances and the emergence of terrifying new ones, the global virus of Trumpism, and a host of other catastrophes are foremost on many of our minds. Rugoff signals his mission—along with its slipperiness—in the biennale’s oft-noted title: May You Live in Interesting Times. (The phrase happens to be not only equivocal but also spurious—its origins lie in a sloppy bit of early-twentieth-century British orientalism, when some statesman or other erroneously cited it as a bit of Chinese wisdom.)

To his credit, Rugoff is sensitive to the idea that mapping aesthetic responses to this moment requires a pluralistic range of voices and points of view, as demonstrated by the refreshingly gender-balanced, racially diverse, geographically dispersed, not-from-the-same-five-blue-chip-galleries roster of artists he has included in the portion of the biennale he’s directly responsible for curating—a mammoth group show of multiple works by each of the seventy-nine chosen artists that complements the eighty-nine national pavilions also on view. The “curating” part of the equation is equally crucial to Rugoff. By this, I mean that it is not just the art that bears the burden of confronting our present; for Rugoff, the method of presenting it does as well. In this, he fares less well.

The Curatorial Conceit

Rugoff sought to select artists whose practices are “multivalent” (they deal with many issues and ideas at once) and “multidimensional” (they often span a range of media and modes of address), who operate “in the spaces between our customary categories,” and who straddle “different genres, conventions, and imagery from seemingly unrelated cultural arenas.” Quoting one of the artists in the exhibition, the Ethiopian-born, US-based painter Julie Mehretu, he frames this heterogeneity—which he sometimes describes as contradiction, ambivalence, or even meaninglessness—as having a political tenor: “I am looking,” says Mehretu, “for that space where you can’t have that singular, particular, experience. It’s about what is undefined, unstable, and for me, that’s important politically. There’s always a multitude of ways of seeing. The effort to control and delineate—that is really part of a different project. It’s a project of power.”

Julie Mehretu, 2017–18. Ink and acrylic on canvas. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

This observation led Rugoff to two important curatorial decisions. First, he decided to split the curated portion of the biennale into two separate shows, titled Proposition A and Proposition B, the former presented in the long, one-room-after-another Arsenale (a medieval edifice built for the city’s shipping industry and that since 1980 has been used as an exhibition space), and the latter in the Central Pavilion at the Giardini, the other major site of the biennale. Each of Rugoff’s two Propositions includes the same group of artists, often working in radically different forms. The structure has the advantage of demonstrating something that is pretty prevalent in today’s art world, which is that artists feel much less bound than in the past to working in a single medium, but it has the disadvantage of making an already unwieldy endeavor even more cumbersome than usual.

Arsenale. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The second curatorial decision that led from Rugoff’s embrace of a political incoherence is that the exhibition eschews a strong point of view. Rugoff writes in the catalog about how he chose to deal with the multifarious range of artwork on view by avoiding an “overarching narrative or thematic umbrella,” in the hopes of not limiting the complexity of the art on display or viewers’ interpretations of it. He frames this decision as one of ceding authorial control, although he admits, parenthetically, “And how, in any case, could so many disparate practices be squeezed into a singular thematic package?”—which seems closer to the truth. Incoherence, then, is the conceptual price one pays to have these artists grouped together in this exhibition, apparently.

In my most generous moments, I could see the ways this curatorial approach might allow viewers to create their own narratives as they make their way through the (at times, seemingly endless) show, but most of the installation does not reward attempts to discover a logic. Yes, that room could have been a meditation on the range of devastation caused by economic inequity, and that room could maybe be about the visual language of Pop updated for the digital age. But that might have been my own projection, my own optimistic (cruelly optimistic?) search for meaning. Exhibition as Rorschach test is my least favorite genre.

But There Was Some Great Work on View . . .

Zanele Muholi, 2015–18. Wallpaper. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Still, there are some powerful threads running through the show, and some terrific art to be seen. A number of works (mostly by women) take on the idea of the self-portrait and the power of self-representation. Zanele Muholi’s wallpaper, composed of large-scale photographic images of the artist that combine uncomfortable references to racist stereotypes with a defiant, powerful, and even confrontational gaze, recurs throughout the Arsenale, around doorways and in interstitial spaces, acting as a continual challenge to viewers. Other standouts in this category include deadpan photos by Martine Gutierrez, produced for her self-created Indigenous Woman magazine in which she poses suggestively with mannequins in high-style scenarios, and Mari Katayama’s images of herself in her bedroom, surrounded by things she has made or collected—including doll-like body doubles and outgrown prosthetics that she has used over the years as a result of a double-leg amputation.

Mari Katayama, 2011–17. Mixed media. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Environmental crisis is a clear concern for many of the artists’ pieces, including Yin Xiuzhen’s sculptures, composed of consumer electronics and discarded clothes fashioned into monumental and ambivalent odes to carbon footprint–heavy airplane travel; Hito Steyerl’s video installations, both dealing directly with Venice’s prospects as sea levels keep rising, and with our often unrealistic fantasies of AI’s capacity to predict the future and our fate in it; Christine and Margaret Wertheim’s intricately crocheted coral reefs; and Anicka Yi’s Biologizing the Machine (tentacular trouble) (2019), composed of massive, glowing pods shaped from kelp fronds that blur the line between animal, vegetable, and human.

Anicka Yi, Biologizing the Machine (tentacular trouble), 2019. Algae, acrylic, LEDs, animatronic moths, water, pumps. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

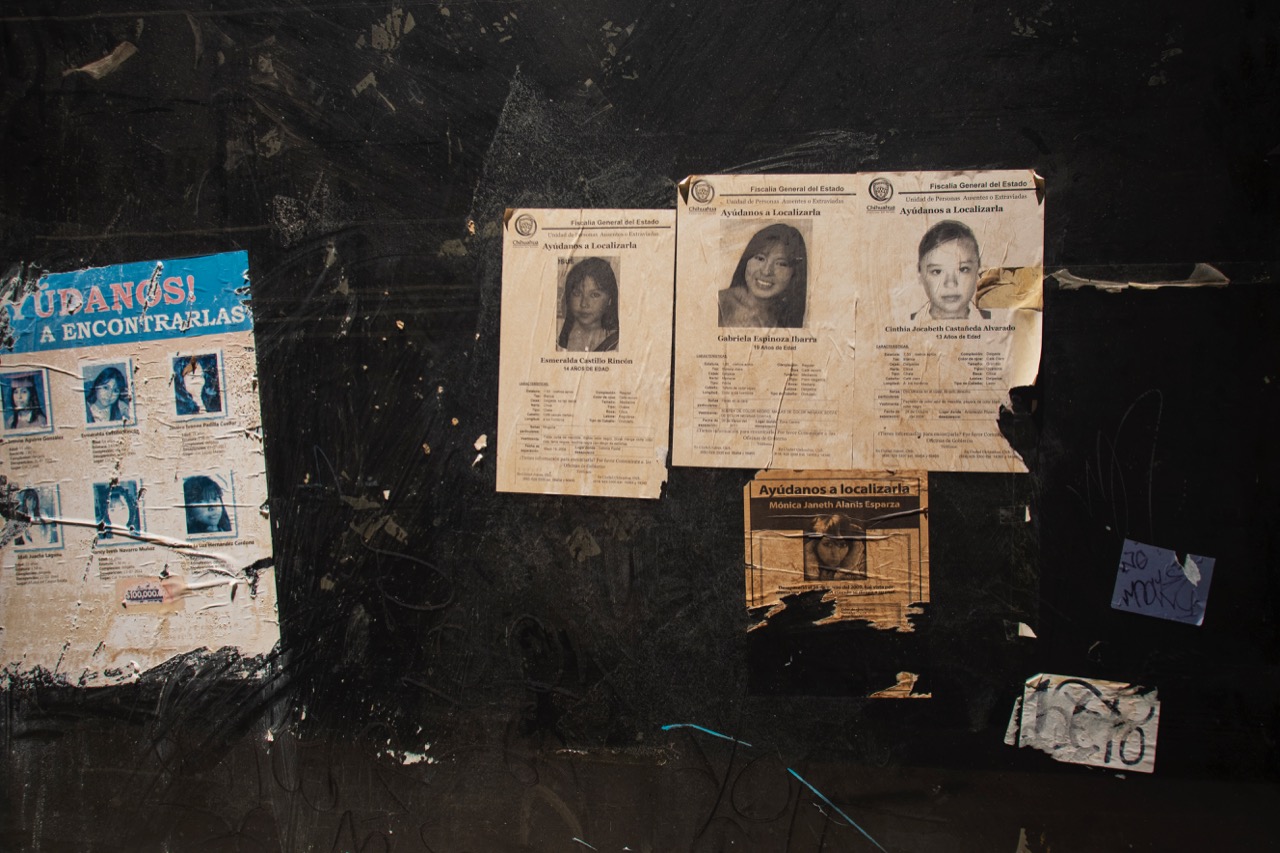

Borders, refugees, and the violence that accompanies their definitions is the theme of Teresa Margolles’s La Búsqueda (2) (2014), a work that calls attention to the waves of women who have gone missing in the border town of Ciudad Juárez, as well as of Neïl Beloufa’s Global Agreement (2018–19), a series of Skype interviews with young soldiers from around the world, which only become visible if you sit awkwardly on uncomfortable gym contraptions—voyeurism doesn’t come without a price. A gently humorous and moving piece by Halil Altindere, centered on his encounter with the only Syrian to ever travel to space, proposes sending migrants to Mars if no one on Earth wants them (Space Refugee, 2016).

Teresa Margolles, La Búsqueda (2), 2014. Intervention with sound frequency on 3 glass panels. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Among the works tackling questions of archives and the construction of histories (including false ones) are Tavares Strachan’s Hidden Histories (2018), neon sculptures referencing the Caribbean intellectual Derek Walcott and the fourteenth-century Venetian writer Christine de Pizan, and his other works commemorating the first African American astronaut, Robert Henry Lawrence Jr.; Ed Atkins’s strange pseudo-historical reconstruction around the theme of historical food practices; and Shilpa Gupta’s For, in your tongue, I cannot fit (2017–18), which takes on the violence of censorship by presenting microphones reverse wired to function as speakers that transmit the recorded recitations, in multiple languages, of the verses of one hundred poets imprisoned for their work.

Shilpa Gupta, For, in your tongue, I cannot fit, 2017–18. Sound installation with 100 speakers, microphones, printed text and metal stands. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The realm of the child—beings who live in a world that constantly challenges their innocence, perhaps—is evoked in multiple contributions to the show, including in Ad Minoliti’s giant versions of children’s toy blocks and life-sized stuffed animals, Frida Orupabo’s paper doll–like collages of black women, and, more eerily, in Kaari Upson’s installation There Is No Such Thing as Outside (2017–19), a stage set–like structure filled with 3-D scanned and enlarged versions of the contents of dollhouses made by her mother and the mother of a friend. Videos of Upson interacting with a body double, projected on screens inside, increase the strangeness quotient, giving the piece as a whole the air of being a spatialized unconscious.

Kaari Upson, There Is No Such Thing as Outside, 2017–19. Mixed media. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

There are also a variety of “primitivisms” on display. One of the most compelling is Cameron Jamie’s Smiling Disease (2008), an installation of masks that the artist commissioned from Austrian craftspeople that reference the Alpine folk tradition of the Perchten, figures related to the demonic Krampus, that terrorizer of naughty children during the Christmas season. Composed of carved wood, sticks, hair, and other materials, the objects replace twentieth-century modernism’s insistent “othering” of primitivism with a homegrown version.

Cameron Jamie, Smiling Disease, 2008. 11 carved masks and 9 carved pedestals. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

And speaking of modernism, a thread of formalist investigations into twentieth-century European art, including Carol Bove’s sculptures and Ulrike Müller’s woven rugs and enamel paintings, serves as a kind of ballast in the otherwise somewhat chaotic installation. In a show that is heavy both on “message art” and on pastiche of many kinds, the deceptive simplicity of Bove’s twisted and dented metal shapes, covered in candy-colored urethane paint, or Müller’s 1930s-feeling quasi-abstractions, have a sort of gravitas—a playful gravitas, if you can imagine such a thing. They wear their conceptual antecedents lightly, while offering really convincing, fresh aesthetic ideas about how vision is always embodied, how the eye can feel as much as see.

Carol Bove, 2017–19. Stainless steel, found steel, and urethane paint. Photo: Maris Mezulis. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The Death of the Curator?

For all Rugoff’s commitment to heterogeneity, plurality, complexity, and nuance, there are many ways in which this show is a clear call to order for the art world. Rugoff’s efforts to cede curatorial authority—his own version of death of the author—is plagued with a structural problem, as Foucault pointed out back in the 1960s: even if you try to kill the author, something always manages to function in its place. In this case, it seems like it’s the market and its need for art stars that fills the void.

One big sign of this was the very pointed decision to award a Golden Lion to the artist Jimmie Durham, a move that feels like an attempt at re-entrenchment by an art-world elite tired of all the protest that has been roiling museums in recent years. Durham was the target of American Indian activists in 2017 and 2018, as a retrospective of his work traveled across the US, over his fuzzy claims to Cherokee heritage; members of the Cherokee nations claimed there was no evidence, whether through records or through social ties, to believe he is Cherokee. A number of artists and writers objected to the way he was being allowed to take up space on museum schedules that rarely, if ever, include Indigenous artists. In Rugoff’s statement about his choice to nominate Durham, the curator avoided mention of Durham’s heritage entirely, recasting the artist’s work, which has long drawn upon white settlers’ stereotypes of Indigenous culture, as a kind of universal reflection on otherness. Describing the artist’s use of “natural materials” to evoke “particular histories” (these went unnamed), Durham’s work is thus interpreted as a decades-long meditation on “Eurocentric views and prejudices” that highlights “the oppression and misunderstanding of different ethnic populations around the world by colonial powers.” What a strange gambit—to recuperate a controversial artist by speaking of his work in the most anodyne generalities—at an exhibition that aims, according to its voluminous catalog, to challenge “oversimplification” and highlight nuance in an era of easily digestible sound bites.

Christoph Büchel, Barca Nostra, 2018–19. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The second example of this conservative impulse to re-center the art star is Rugoff’s choice to include in his show the so-called Barca Nostra. The ship, after departing from Libya, sank some 120 miles from Lampedusa on April 18, 2015, when it collided with a Portuguese freighter trying to come to its rescue; only twenty-eight of the estimated 700 to 1,100 refugees onboard were accounted for after the wreck. The vessel was recovered from its watery grave to aid investigators, and in the aftermath of such analysis has been the subject of much debate—should it be moved to Brussels as a monument to the consequences of Europe’s intolerance of migrants, should it be preserved as memorial, should it be refashioned as human rights museum, and so on. Displayed for the first time at the Venice Biennale, set on rusted metal supports alongside the canal across from an open-air café in the Arsenale section, marked out only by insubstantial cordons and an easily overlooked wall label some distance away, the boat’s inclusion in an art exhibition has left a bad taste in the mouths of many—and rightly so.

The catalog identifies the work as “a project initiated by Christoph Büchel in collaboration with the Assessorato Regionale dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana, the Comune di Augusta, and the Comitato 18 Aprile 2015.” While Büchel and his collaborators see the shipwreck as “a collective monument and memorial to contemporary migration . . . dedicated to the victims and the people involved in its recovery” and “the collective policies and politics that create these kinds of wrecks,” and declare their intent “to actively use Barca Nostra as a symbolic vehicle of significant socio-political, ethical, and historical importance for the living, those who remain behind and future generations to come,” the fact remains that this is not a monument or a memorial or a conceptual vehicle so much as a coffin. What does it mean for an artist—even as part of a collaboration, as a gesture of social practice—to relocate the site of so many deaths (many of them still unaccounted for) into an exhibition? What does it mean for an artist to attach his name—even as part of a list—to this boat? As a thing as such, the Barca Nostra is unquestionably moving—the tears in the hull are visceral, turning it into a metonym for the bodies that perished within it. But as a project put forth by Büchel in an art context it’s indefensible: it’s hard to read as anything but a co-optation of real suffering and death in the name of aesthetic spectacle, especially distasteful because it’s a white European artist appropriating the real violence visited on brown and black migrants by exclusionary and inhumane immigration policies. Graveyards aren’t readymades.

The National Pavilions

Pavilion of Switzerland, Moving Backwards. Photo: Francesco Galli. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

When I entered the first, darkened gallery of the Swiss pavilion, nestled in the Giardini, a glittery, fringed curtain opened and closed in front of a wall-sized projection of people moving in joyful and energetic ways to what my middle-aged ears sounded like club music. One curious thing, though: these dancers’ shoes were on backward, and their movements seemed in reverse. Exiting the dark room into a courtyard, the idea became clearer thanks to a statement to visitors by artists Renate Lorenz and Pauline Boudry:

We do not feel represented by our governments and do not agree with decisions taken in our name. We witness European nations building giant walls and fences around borders that already didn’t seem useful in the first place, rejecting rescue ships at the harbors . . . People stop using gender-neutral language and move from their polyamorous groups into traditional families. Hate speech not only seems acceptable, but becomes a motor of aggressively arresting us into what is considered a normal life. Do you sometimes feel as if you are massively being forced to move backwards?

Citing as inspiration women of the Kurdish guerilla groups who wore their shoes back to front as they walked through the snowy mountains to outwit their pursuers, the duo propose a collective moving backward as “a means of coming together, re-organizing our desires, and finding ways of exercising freedoms.”

Halil Altindere, Neverland Pavilion, 2019. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Paradoxically, it is not Rugoff’s curated show that feels forward-thinking—rather, the super-retro national pavilions, those relics of a fin-de-siècle internationalist optimism, hold the most interest when it comes to pinning down the stakes of artmaking at this historical juncture. Yes, there are problems with the format. For one, the differences in the national pavilions—ranging from the perfectly climate-controlled, luxury-gallery feel of the US pavilion to the photocopied labels taped on the wall of the scrappy Venezuelan pavilion to the Golden Lion–winning Lithuanian pavilion, which resorted to crowdfunding in order to pay its performers beyond the opening week of the exhibition—reflect a little too closely the divide between haves and have-nots that frames international relations at the moment. For another, the idea of nation itself becomes increasingly irrelevant when you realize how many millions of people are living in a condition of statelessness in the face of geopolitical upheaval. The Turkish artist Halil Altindere takes on this problem with his Neverland Pavilion (2019), a structure consisting only of a Palladian façade with nothing but scaffolding behind it—a devastatingly appropriate site for refugee artists who don’t fit into the antiquated structure of this exhibition.

Pavilion of Ghana, Ghana Freedom. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Despite all the drawbacks of the national pavilion model, it has allowed artists from all over the world to participate in the exhibition even when the central section skews Euro-American, as has almost always been the case. Ghana has mounted its first-ever pavilion this year, in a space at the Arsenale designed by David Adjaye and curated by Nana Oforiatta Ayim. It includes a who’s who of Ghanaian artists in the diaspora, including El Anatsui, John Akomfrah, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, along with Ibrahim Mahama, Selasi Awusi Sosu, and Ghana’s first known female photographer, Felicia Abban. Meanwhile, other countries’ pavilions introduced me to artists I had never encountered before; among the standouts are the UAE pavilion, with a two-channel video installation by the poet and filmmaker Nujoom Alghanem; the deeply affecting and tightly curated Korean pavilion, featuring works by Siren Eun Young Jung, Jane Jin Kaisen, and Hwayeon Nam that meditate on questions of lost and regained histories, often through the medium of dance; and the Brazilian pavilion, where Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca present photos and a video installation titled Swinguerra (2019) that shines a light on dance battles waged by young people in a country where racial tensions run deep. Pointedly, Ukraine’s contribution is offered by a collective that gathered the names of every living Ukrainian artist and loaded them onto hard drives, with the intention of flying them over the opening of the biennale in a cargo plane—the world’s largest—made in a Ukrainian factory in the Soviet era. The gesture, I was told by one of the participating artists, was to literally cast a shadow over an exhibition by artists who are most often left in the shadows. But when the Ukrainian government halted the flight before the opening, the shadow became something like an urban legend—think people running around the Giardini looking for the plane, worried that they missed it.

Pavilion of Chile, Altered Views. Photo: Italo Rondinella. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Many of the pavilions address a similar range of issues as those present in the curated show, but have the advantage of not competing with the chaos of being installed tooth and jowl with other, often unrelated, works. One of the most striking of these is the Chilean pavilion, which deals with questions of reimagined archives and histories. Voluspa Jarpa’s labyrinthine installation, consisting of three parts—the Hegemony Museum, the Subaltern Portrait Gallery, and the Emancipating Opera—deconstructs some of the founding myths and fantasies of Eurocentrism, offering in their place the museum as funhouse and horror show by turn in a way that demonstrates the real pleasures of decolonization.

Pavilion of Canada, Isuma. Photo: Francesco Galli. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

In the Canadian pavilion, Isuma, Canada’s first Inuit film production company, founded in 1990 by Zacharias Kunuk, Norman Cohn, Paul Apak, and Pauloosie Qulitalik, presents One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019). The movie, a recreation of a single day in 1961 in which Inuit actors speaking in Inuktitut and English ad lib their way through a reenactment of a lost way of life, demonstrates the impact of the Canadian government’s forced relocation of Indigenous peoples in the Arctic region. It is funny and wry, and unlike so many other video installations lately, it is displayed in a room open to natural light, on multiple screens that can be viewed from ample seating, inviting viewers to take time with the gentle and subtle humor and sharp observations contained in it.

Pavilion of United States of America, Martin Puryear: Liberty / Libertà. Photo: Francesco Galli. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

Martin Puryear’s sculptures in the US pavilion—mostly wooden forms that metabolize his myriad sources, often rooted in African American material cultural traditions, so thoroughly that their insistent formalism becomes a vehicle for a real shift in our all-too-white visual landscape—are exquisitely crafted and subversively elegant. They demonstrate the ways that an almost perversely myopic attention to material can feel entirely radical.

Pavilion of Lithuania, Sun & Sea (Marina). Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Image courtesy La Biennale di Venezia.

The Lithuanian pavilion is one of my favorite art experiences in recent memory: it is beautifully conceived and executed, smart, urgent, imaginative, original, new. In a warehouse located a few minutes’ walk from the Arsenale, artists Lina Lapelyte, Vaiva Grainytė, and Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė have created Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019). Viewers stand in a dimly lit space, looking through a large square cutout in the wooden floor to the basement below. It is, strangely enough, as if we were looking down not on the underworld but on heaven, which in this case takes the form of sunlit beach. Lounging on the sand are bathers of all ages, shapes, and sizes, napping, chatting, lazily playing games, looking at their cell phones—all the while singing an operatic score. At first, the lyrics seem mundane—the “Sunscreen Bossa Nova,” for example, goes something like this: “Hand it here, I need to rub my legs . . . / ’Cause later they’ll peel and crack, / And chap. / Hand it I will rub you . . . / Otherwise, you’ll be red as a lobster . . . / Hand it I will rub you. . . .” Other songs, such as the “Wealthy Mommy’s Song,” which tells of the travels of her coddled son, veer toward a parodic and biting wit. Only after a few minutes do you realize that the torpor of the heat is masking another kind of inertia, alluded to subtly in the words of the songs the people sing: that of our passivity in the face of environmental catastrophe.

Perhaps, then, we are looking at purgatory. It is a peculiar species of hope that tells us we are not yet in hell, and that there is yet time to redeem ourselves. This is indeed the hope we have in our interesting times.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her book Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts was published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is editor of the forthcoming Lorraine O’Grady: Writing in Space, 1973–2019 (Duke University Press, 2019), and is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.