Aruna D’Souza

Aruna D’Souza

A life of permanent exile: recent work from a founder of global feminism.

Zarina, Dark Roads, installation view. Image courtesy the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU.

Zarina, Dark Roads, Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU, 8 Washington Mews, New York City, through February 2, 2018

• • •

What is feminism’s purview? For those women who embraced a nascent form of intersectional feminism in the late 1970s and early 1980s, including Zarina Hashmi—or simply Zarina, as she prefers to be called—it was almost unimaginably broad. Fleshed out in shows like Dialectics of Isolation, which Zarina co-curated with Ana Mendieta and Kazuko Miyamoto in 1980, and in the pages of the “Third World Women” issue of Heresies that she co-edited in 1979, Third World feminisms aimed to smash not only the patriarchy, but all forms of oppression that produced and supported it: capitalism, white supremacy, Western imperialism. For the women of color who imagined (and still practice) this early form of intersectional activism, the personal was political—and the political was conceived at a global scale, one that linked the condition of women of color in the US to those struggling to decolonize themselves abroad.

Like many of her generation, recognition has come late in Zarina’s life; she was included in the inaugural Indian pavilion at the 2011 Venice Biennale, and was the subject of a 2012 retrospective organized by the Hammer Museum that traveled to the Guggenheim. Dark Roads, a small, heart-wrenchingly beautiful show at the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU, co-curated by Zarina herself, provides a glimpse into how her expansive notions of feminism play out in her subtle and minimalist practice. By juxtaposing the woodblock prints, collages, handmade books, and other works on paper on display, Zarina frames her own memories of immigration and travel in relation to the contemporary refugee crisis and the violence that produces it—or rather, she refuses to see her own experiences outside that larger frame. Given that in Syria alone, roughly three quarters of the millions who are fleeing their homes are women and children, this gesture accords fully with the concerns of the intersectional feminism that she articulated early in her career.

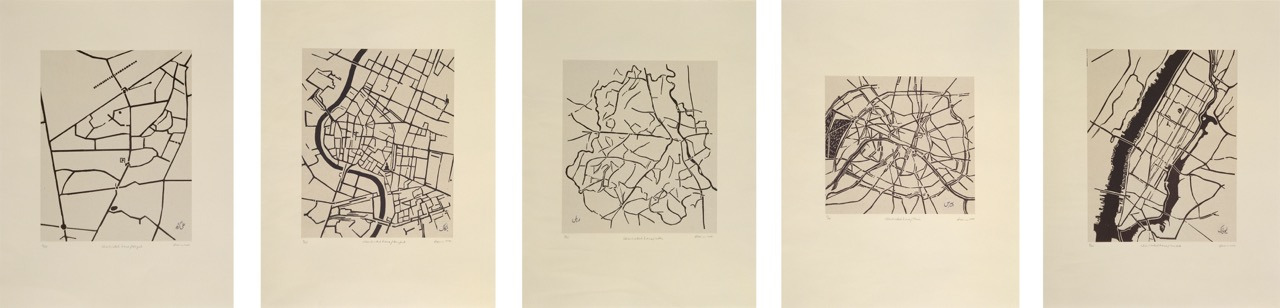

Zarina, Cities I Called Home, 2010. Portfolio of 5 woodcuts and text printed in black on handmade Nepalese paper, dimensions variable. Image courtesy the artist and Luhring Augustine.

Two sets of schematic maps drive the point home. Cities I Called Home (2010) consists of a grouping of five woodblock prints on handmade Nepalese paper, each representing a city where Zarina has lived: Aligarh, where she was born to a Muslim family a decade before Partition; Delhi; Bangkok, where she studied woodblock printmaking while her parents, finding conditions in India untenable, migrated to Pakistan, severing her ties to home, if not leaving her literally homeless; Paris, where she learned intaglio in the studio of S.W. Hayter in Atelier 17; and New York, where she settled in 1976. The names of each place are printed in Urdu on the sheets and penciled in English below. Each city is reduced to a few meandering lines, with waterways and roads almost indistinguishable from one another. In a second portfolio of nine prints, These Cities Blotted into the Wilderness (2003), we see similar pared-down plans of cities where Muslims have been victims of violence: Grozny, Sarajevo, Srebrenica, Beirut, Jenin, Ahmedabad, Baghdad, Kabul. Included in this suite is New York City, which is shown not as a web of streets but by two lines, uninked tracks in a sea of black, representing the World Trade Center; its distinct graphic treatment implies it is an outlier, the record of an act perpetrated by Muslims and used to rationalize the deaths of so many more Muslims in the wars that followed.

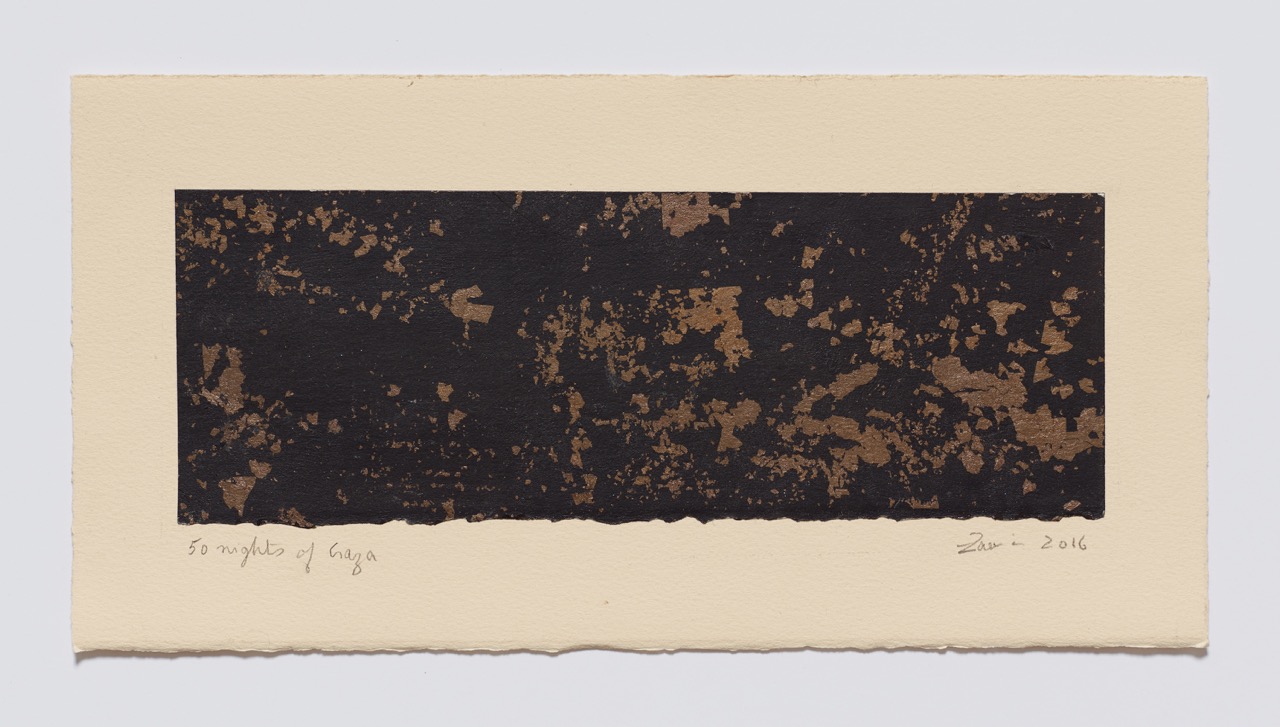

Zarina, 50 Nights of Gaza, 2016. Collage with pewter leaf and BFK light paper stained with Sumi ink, 4.25 × 11.5 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

Cities under siege: this is the prehistory of so many refugee crises. Zarina offers meditations on the violence that precipitates migration and the horrors that result. 50 Nights of Gaza (2016) uses small bits of collaged black-inked paper, as well as delicate pewter leaf, to depict a sky aglow with mortar fire; Some Houses Don’t Fall (2016) deploys pewter, now supplemented with gold, to evoke, with subtle irony, the fragility of stone and cement. In No Escape I and II (2015) we see drone bombers at the center of a graphic, angular web made up of collaged strips of paper, chillingly reproducing the ways in which their operators view their targets not as people or even towns, but as coordinates. Refusing to let us forget that such experiences are not simply taking place in war zones but are part of our daily lives, too, Surveillance Across the Hudson (2015) shows an insect-like flying craft above a jagged rectangle that suggests, in an impossibly opaque black, the water below.

Zarina, A Child’s Boat for Aylan and Ghalib, 2015. Installation view. Image courtesy the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU.

Water is both freedom and its opposite in Zarina’s recent work. Lost Boat; Sinking Boat with a Heartbeat; Rohingyas: Floating on the Sea of Memory; Year of the Sinking Boats; A Child’s Boat for Aylan and Ghalib; these images, all from 2015, recall, despite their simplicity, the desperation that leads Muslim refugees to cross the sea—Syrians attempting to get to Greece and Italy, or the Rohingyas escaping genocide in Burma. A Child’s Boat for Aylan and Ghalib—a tribute to five-year-old Ghalib and three-year-old Aylan, whose corpse, photographed washed up on shore, shattered so many of us—fashions a gift for these two young casualties of Syria’s cruel displacements: a simple boat folded out of paper like the ones children make, set against a black, even ominous, background. Such simple origami forms recur on land, in Refugee Camp (2015), where layered triangles are attached to their paper support with delicate black thread, arrayed in a strict grid that suggests an orderliness defied by the fragile paper, which curls at the edges ever so slightly, refusing to lay quite flat.

Zarina, Book of Travels, 2012. Accordion Book, 11.5 × 42 inches (open). Image courtesy the artist.

If Zarina, through the most economical means, manages to convey the pathos of the modern refugee, it is not by posing dislocation as the polar opposite of location. There is no fetishizing of the fatherland in this work. She has said that she considers herself a permanent exile, and seems to regard life as a constant movement through space. She intimates as much in Book of Travels (2012), which takes advantage of the accordion book form with its continuous folded surface. Here, her biography is rendered conceptually, as an abstract, woodblock-printed line that runs along one side of a sheet of cream paper, switching back, reversing, and taking detours on occasion, but ultimately sticking to its onward journey across the long expanse. On the paper’s other side, Zarina lists the names of the cities where she’s been. The effect is, paradoxically, a map that, by being a trajectory, manages to encode time.

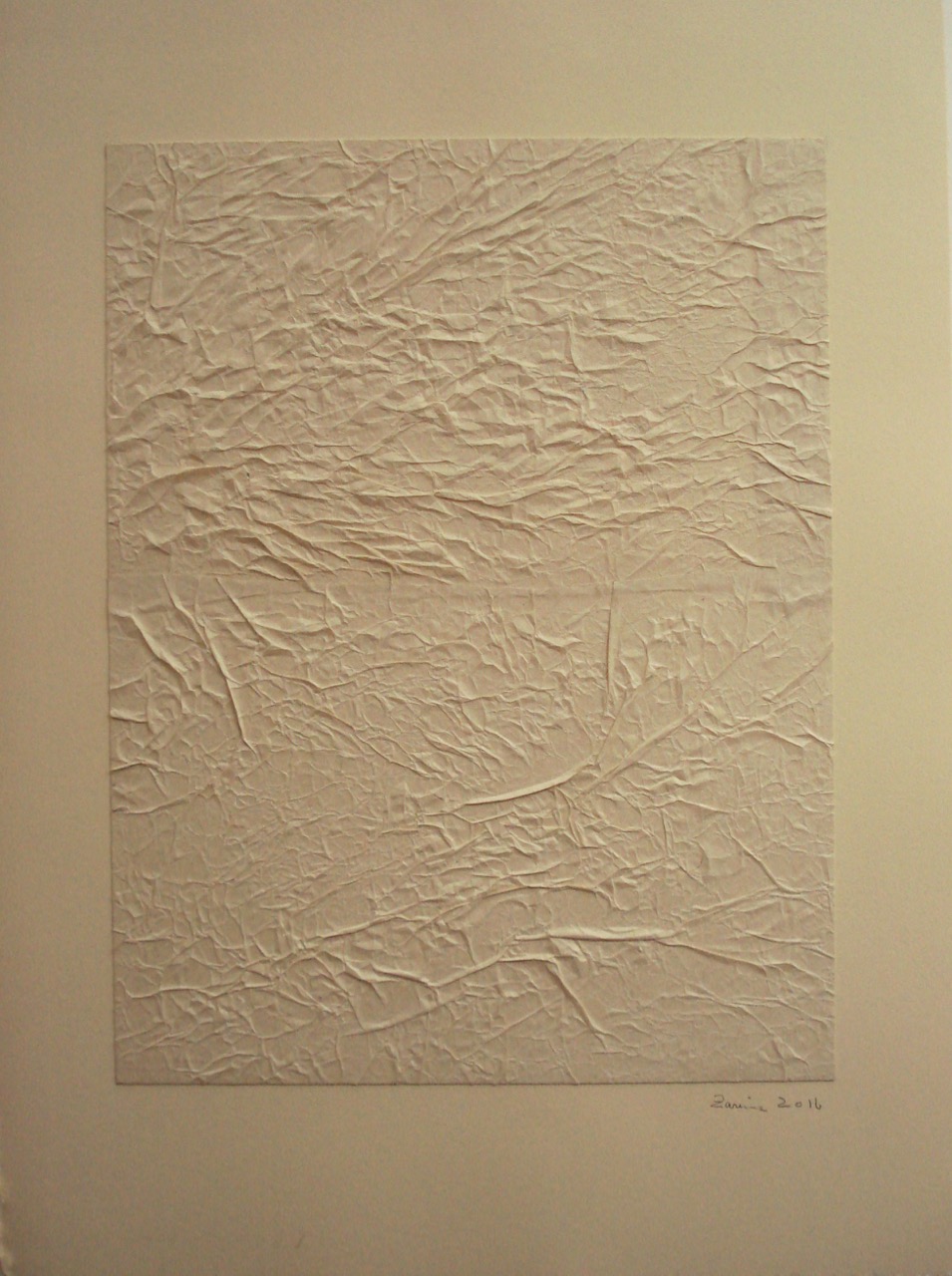

Zarina, Starting Over, 2016. Crushed Indian handmade paper, 18.5 × 14 inches. Image courtesy the artist.

But this movement, this exilic condition, involves a constant refashioning, a prospect either exhilarating or exhausting. Starting Over (2016) depicts this complexity in the most extraordinarily succinct way: it consists only of a sheet of handmade paper that is crumpled up tightly and then smoothed flat again. You can see the wrinkles; you can practically feel the gestures of the hands that pressed it gently and repetitively to erase the signs of what it’s been through. How to read this gesture? As an act of near-destruction, in which the pristine paper is forever marked by the pressures to which it has been subjected, or a record of resilience, whereby the sheet is made infinitely more fascinating by the tracery of wrinkles on its surface? The answer surely depends, in part, on where you’ve come from, and how you got there.

Aruna D’Souza is a writer based in Western Massachusetts. Her writings on art, feminism, culture, diaspora, and food have appeared in Bookforum, Art in America, Time Out New York, and the Wall Street Journal. She is currently working on a volume of Linda Nochlin’s collected essays to be published by Thames & Hudson. Whitewalling: Art, Race, and Protest in 3 Acts will be published by Badlands Unlimited in May 2018. She is a member of the advisory board of 4Columns.