Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Out of San Francisco’s electronic past: live improvisations with the Moog.

San Francisco Moog: 1968–1972, by Doug McKechnie, VG+ Records, available on Bandcamp

• • •

In California in 1968, a man by the name of Doug McKechnie—a young army vet and psychedelic explorer who had dropped LSD with an acolyte of Timothy Leary in 1966—recorded secret experiments with a Moog modular synthesizer in a loft known as the San Francisco Radical Laboratories. McKechnie had access to one of a handful of Moog modular Series III synthesizers in the world; it belonged to his erstwhile roommate, Bruce Hatch. The same Moog that McKechnie used for his sonic investigations was later sold to Tangerine Dream, the now-legendary German group that launched in 1970 with the album Electronic Meditation.

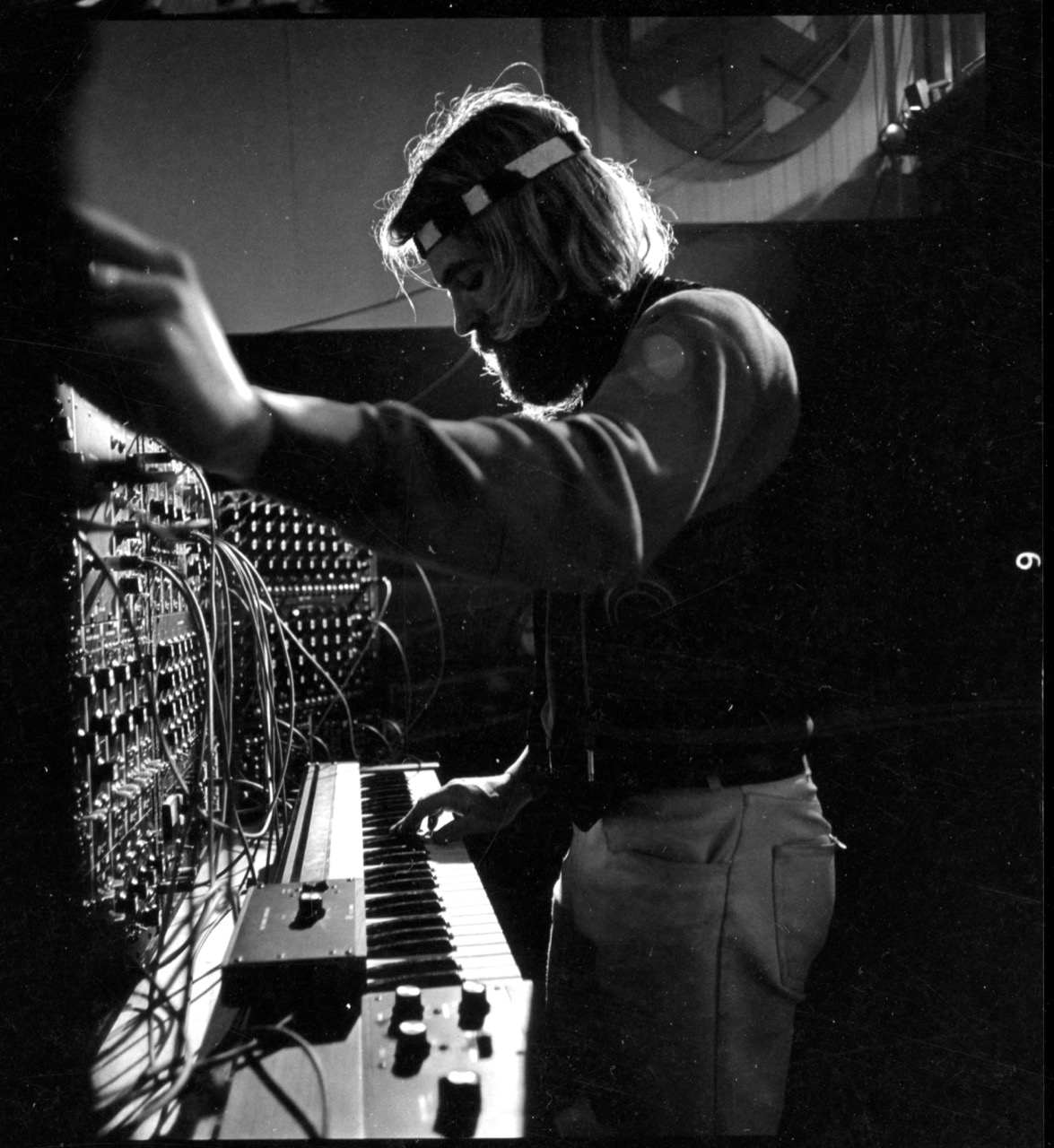

Doug McKechnie with the Moog modular synthesizer, 1969. Photo: John Pierce. Image courtesy Doug McKechnie.

The first instruments we now know as synthesizers were independently invented by Robert Moog and Don Buchla in 1963; by the late 1960s they were still a relatively rare commodity. The Bay Area counterculture then was primarily known for rock—bands like Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and the Grateful Dead. But under the surface, pure electronic music—abstract, entirely synth-driven, sans vocals—was percolating too. A fascinating new album called San Francisco Moog: 1968–1972 collects some of McKechnie’s little-known work from this fertile period.

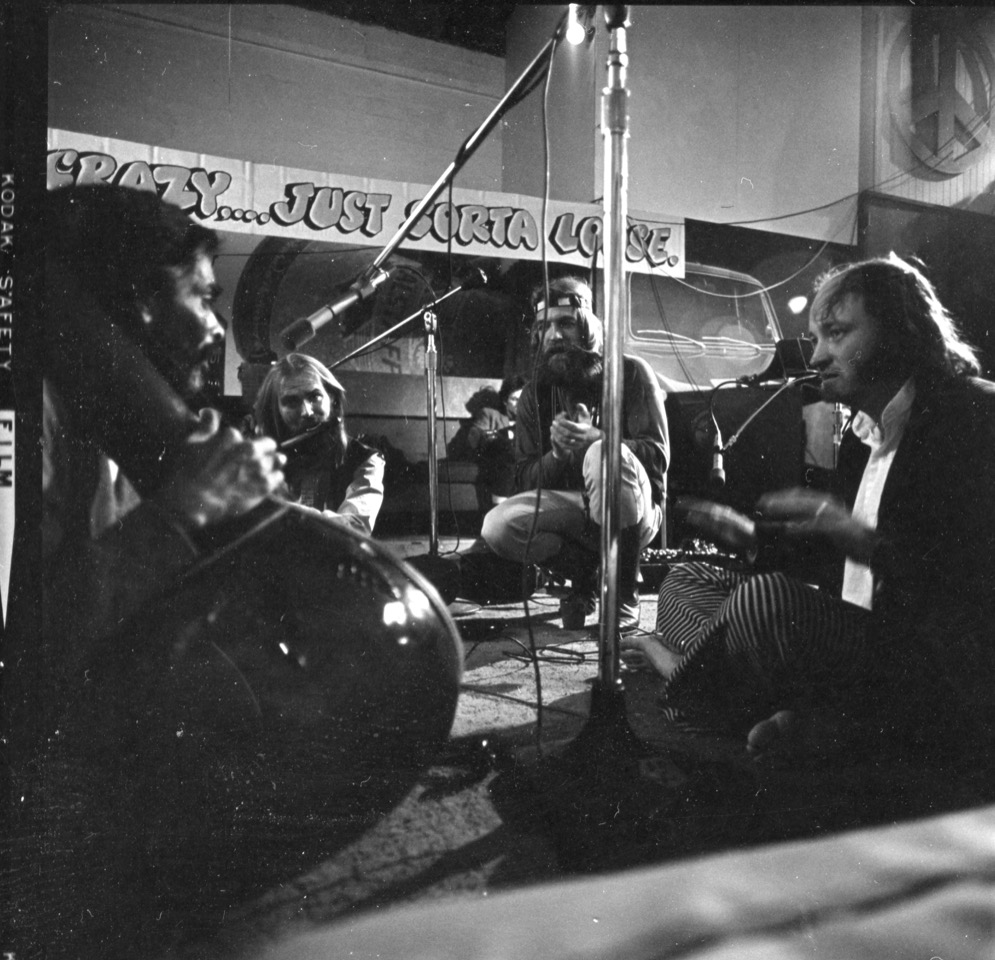

Doug McKechnie performing with the Moog at Altamont, 1969. Photo: John Pierce. Image courtesy Doug McKechnie.

San Francisco Moog is a rolling expanse of sound, spread over five live tracks. The quiescent, meditative pulse of the music has much more in common with what would come to be known as the Berlin school of German electronic music than anything coming out of the US at the time. That makes sense, since Tangerine Dream, the centerpiece of the Berlin school, employed the same Moog, also utilizing its two twenty-four-step sequencers. Early Tangerine Dream albums such as Phaedra (1974) share an ethos with McKechnie’s work, but they are sleeker and more refined than his appealingly chaotic ride. Stateside, the most prominent album involving the Moog was Wendy Carlos’s Switched-on Bach, released in 1968, which was impressively fastidious in its recording and production, an elegant and polished fusion of classical music and electronics. On the quirkier end of the spectrum, the Canadian composer Mort Garson released an album called The Zodiac: Cosmic Sounds in 1967, which featured Moog sounds played by Paul Beaver.

McKechnie’s recordings are unique in their roughness, lending an early window into the massive, lumbering Moog as a live instrument. This is sonic improvisation in real time, with no overdubs, without a studio. The room is palpable; you can feel the energy of the audience. San Francisco Moog is also a document of a particular moment in the city’s storied history, with its geography slowly unfolding over the tracks.

Harish (Hanuman the Monkey God), Dan Errkla, Doug McKechnie, and Terry Riley at the San Francisco Radical Laboratories, 1968. Photo: John Pierce. Image courtesy Doug McKechnie.

The album opens with “The First Exploration @ SF Radical Laboratories, 1968,” recorded at McKechnie’s bygone loft on 759 Harrison Street in San Francisco (back then, the huge, 2,500-square-foot space was rented for $250 a month). The moody, melodic tune carries the vibe of the time; you can practically smell the incense burning and see the candles flickering. The upbeat, riotous throb of “Crazy Ray” is an homage to Ray Anderson, founder of the West Coast light show known as the Holy See. “Berkeley Art Museum” is a thirteen-minute recording from the opening week of performances at the unveiling of the original Berkeley Art Museum in 1971, suffused with reverb from the cavernous, thick-walled space. “The echo in that place was extraordinary,” McKechnie told me when I talked to him for this piece. “It was like infinity, the depth. That’s one of the reasons why I said we need to hear the room, not just the synthesizer. We put the omnidirectional mic . . . To hear the sounds in that space was extremely exciting, I mean really exciting, and part of that excitement gets transmitted.”

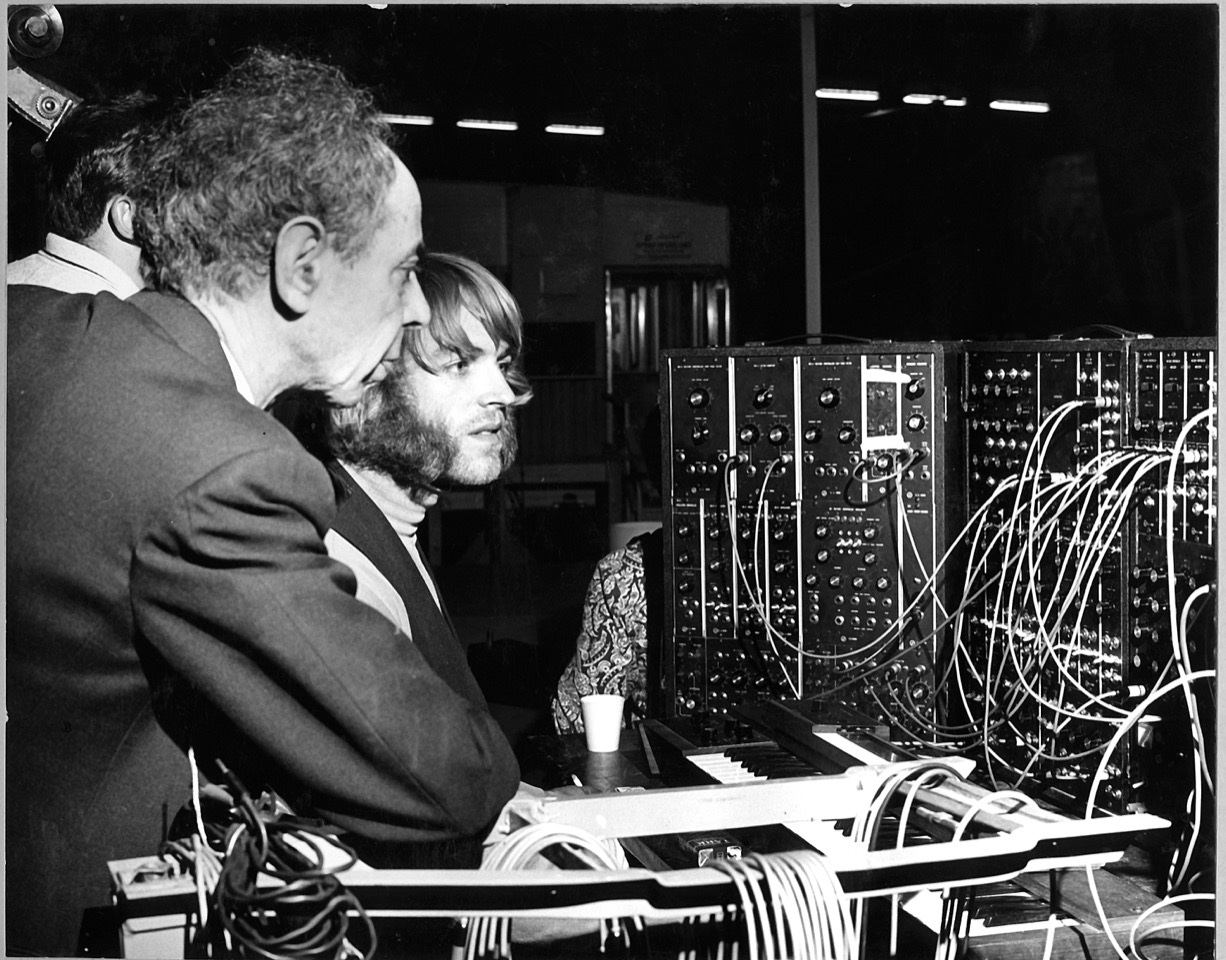

Dr. Frank Oppenheimer and Doug McKechnie at the opening of the Exploratorium in San Francisco, 1969. Image courtesy Doug McKechnie.

Electronic music in the 1950s and 1960s was closely tied to academia and studios, but McKechnie was not a part of any institution, preferring to work in the underground. In the Bay Area, Mills College in Oakland and the San Francisco Tape Music Center would have been the two obvious places to study this emerging new music. McKechnie was not affiliated with either—though he did cross paths with the longtime Mills professor and composer Terry Riley, playing the Moog in 1969 for an early performance of Riley’s landmark piece “In C” at the San Francisco Opera House.

Doug McKechnie, 1969. Image courtesy Doug McKechnie.

McKechnie termed himself a “catalytic agent,” not a musician. He got to know people like Alan Watts, a prime exponent of the Zen movement in the US, when they met at one of McKechnie’s concerts on an old ferry boat in Sausalito. He befriended the late filmmaker Jordan Belson, who was living in a dank basement apartment on Telegraph Hill, and became involved with the Vortex concerts. (A tidbit of McKechnie’s music is in the Belson film Light, from 1973.) In the late 1960s, McKechnie began giving free-form, metaphysical lectures about the synthesizer, beginning every talk with the mysterious pronouncement “All things manifest in waveforms.” “I would explain how the inside of the mouth was the high and low pass filter, and I could do with my mouth what I could do with the synthesizer,” McKechnie recalled to me. “People were just not used to listening to that kind of sound. One of the reasons that my music holds up now is because the public has gotten used to hearing the tonalities of electronic music.”

San Francisco Moog is a welcome surprise—an uncovered gem from very well-trodden territory. Over the half-century since the 1960s ended, it has seemed like every aspect of the counterculture has been documented, with the mammoth thirty-eight-CD Woodstock box set last year the apparent culmination of this laborious process. Finding something so novel opens a small new pathway into the history of electronic music—an odd node from the US to Germany by way of San Francisco hippie culture and emerging modes of listening.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.