Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Battling hate and the Whitney: a history of the Asian American

activist group.

Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001, edited by Howie Chen, Primary Information, 550 pages, $30

• • •

It is profoundly empowering to learn about the history of Godzilla, the radical collective of Asian American artists, writers, and curators established in New York City in 1990. The group quickly became an important activist effort for bolstering Asian American representation in the arts. I wish I’d had access to Godzilla in the early 1990s, as a South Asian growing up in New Jersey without a cultural map. My high school was almost thirty percent Asian, but I didn’t see people who looked like me on television or in movies, music, magazines, and museums. My best friend was Taiwanese, and the only times we viewed our cultures represented in a public setting was at restaurants. Multiculturalism was a popular 1990s buzzword, but it didn’t reflect the reality we witnessed every day in mainstream media—and indie and underground culture weren’t much better. Part of the reason I became an arts critic was to try to change that.

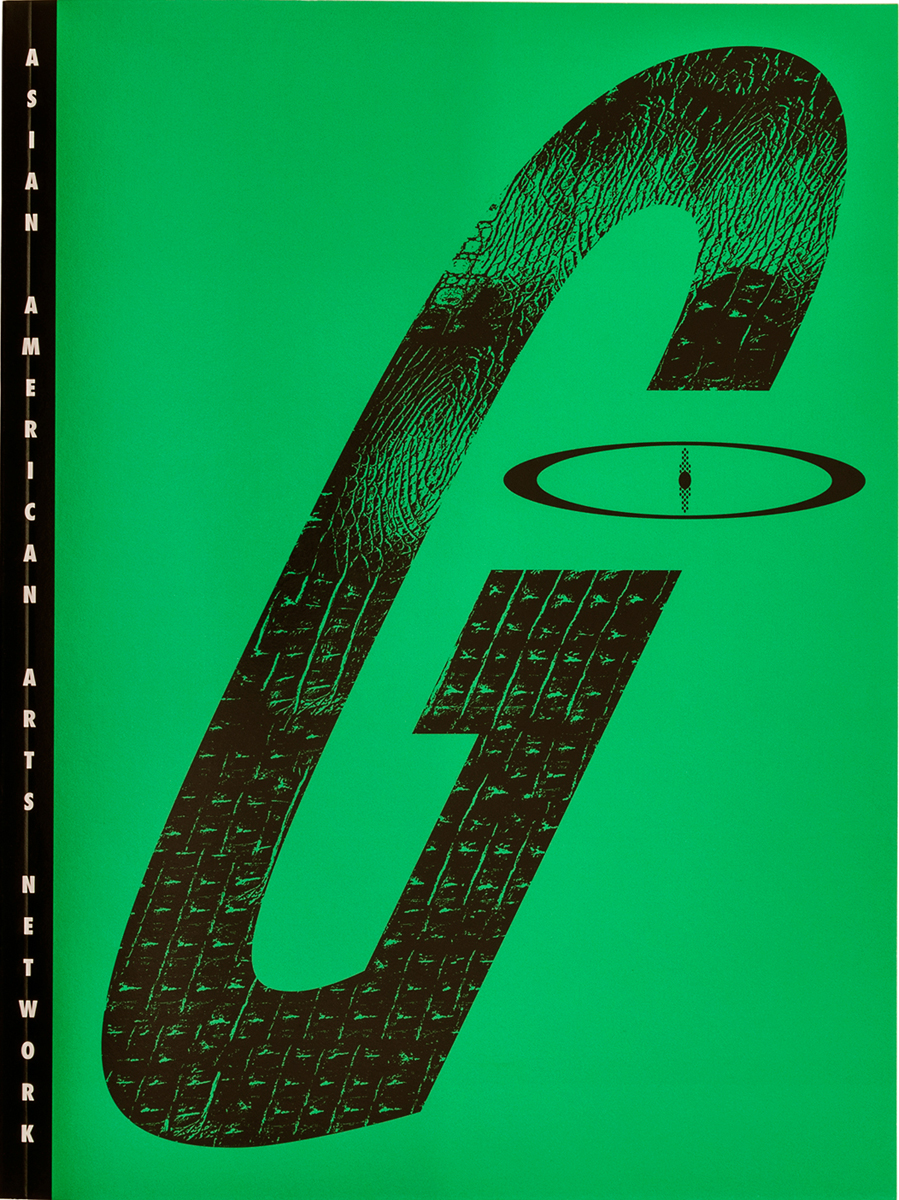

Godzilla Newsletter 2, no. 2 (Winter 1992). Courtesy Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network and Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network Archive; MSS 166; Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU.

Until now, Godzilla’s legendary newsletters and other materials, many of them produced before the advent of the World Wide Web, have been relatively difficult to find. An inspiring new book released by Primary Information, Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001, compiles the organization’s work into a 550-page volume. Edited by the curator Howie Chen, the massive compendium contains letters, newsletters, essays, interviews, proposals, meeting minutes, flyers, photos, advertisements, and other ephemera created by the group. Dot-matrix printouts and vintage Mac fonts abound, and the newsletter echoes the scrapbook-y style of the zine culture of the time. Arranged chronologically and roughly divided into sections by year, the book provides copious documentation of how Godzilla grew in size and impact, long before the days of social media. Godzilla had its roots in Brooklyn in 1990, in a small meeting in a studio attended by the artists and original founders Ken Chu, Margo Machida, and Bing Lee. Several other artists soon joined, expanding Godzilla’s New York footprint, and by the mid-’90s the group had nearly two thousand members nationwide.

Group portrait of the members of Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network, taken in 1991 for the cover of Godzilla Newsletter 1, no. 1 (Spring 1991). Back row (L–R): Byron Kim, Bing Lee, Eugenie Tsai, Karin Higa, Arlan Huang, Margo Machida, Charles Yuen, Janet Lin, Helen Oji, Colin Lee, Tomie Arai. Front row (L–R): Ken Chu, Garson Yu. Photo by Tom Finkelpearl. Courtesy Tomie Arai.

The first section of the book, “Origins,” offers a window into a bit of 1980s prehistory, with letters, timelines, and other papers, along with a reprint of a book chapter by Machida titled “Seeing ‘Yellow’: Asians and the American Mirror.” Godzilla didn’t emerge out of nowhere—they viewed themselves as part of a lineage going back to the activist culture of the 1960s. “Godzilla produced a timeline that mapped its roots to the West Coast’s Asian American movement of the late 1960s, and more directly to Basement Workshop, founded in 1970 in New York’s Chinatown,” writes Chen. “In response to the sociopolitical and racial changes in the United States, predecessors of Godzilla such as Basement and the Kearny Street Workshop in San Francisco took inspiration from Third World internationalism, the Black Power movement, the Chicano movement, and the anti-war, labor, and feminist movements, linking political struggle with art production to serve their communities.”

The next section of the book, “1990,” begins with the minutes of the first meeting, which were recorded in great detail. Many ambitious proposals were put forth in that meeting, including for a “publication/journal/newsletter” focusing on Asian American art, an exhibition tracing Asian American community arts movements in the 1960s and 1970s, and the establishment of an Asian American art museum and library. Further meetings, meticulously documented in the minutes reprinted in the book, underscore how directed Godzilla was from the start, and how quickly the membership expanded.

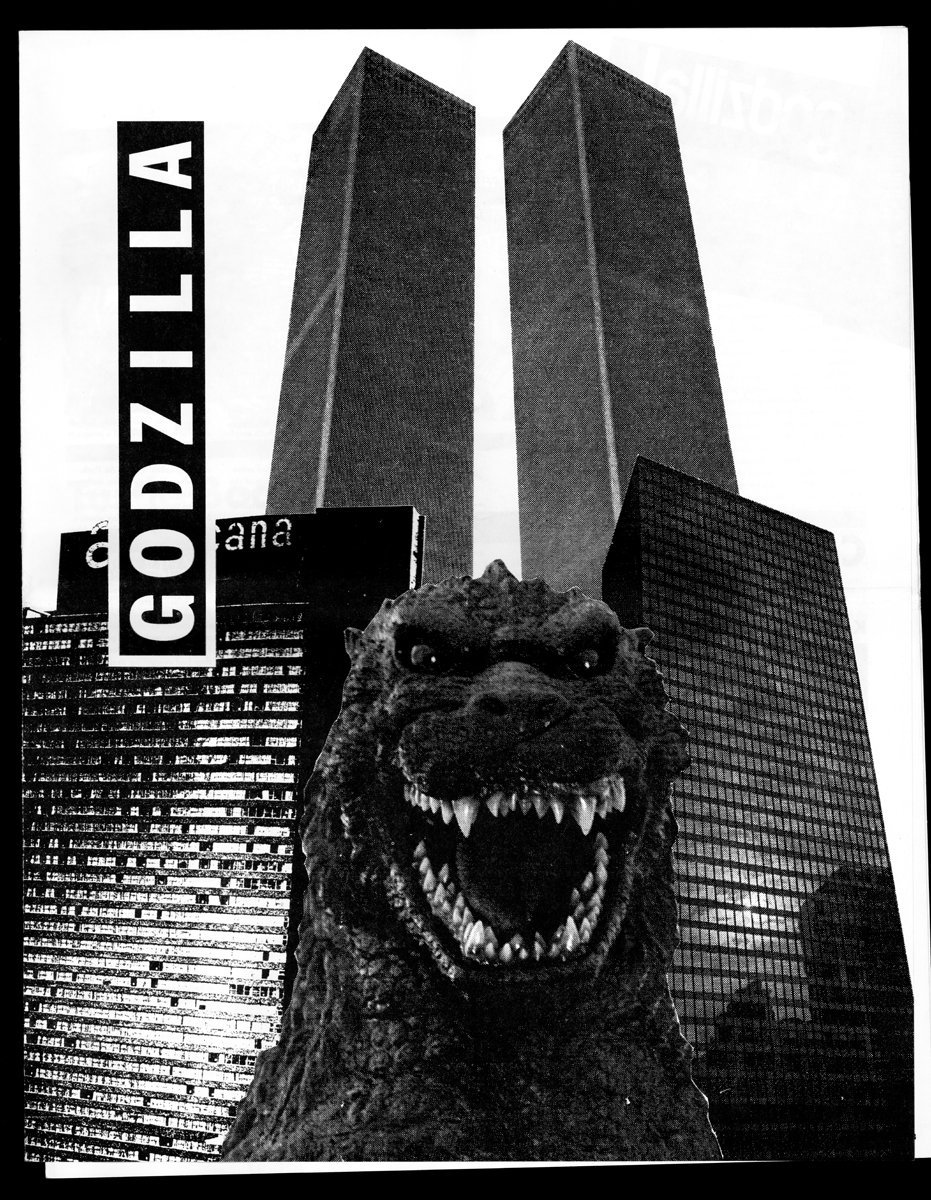

Godzilla Newsletter 1, no. 2 (Winter 1991). Courtesy Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network and Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network Archive; MSS 166; Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU.

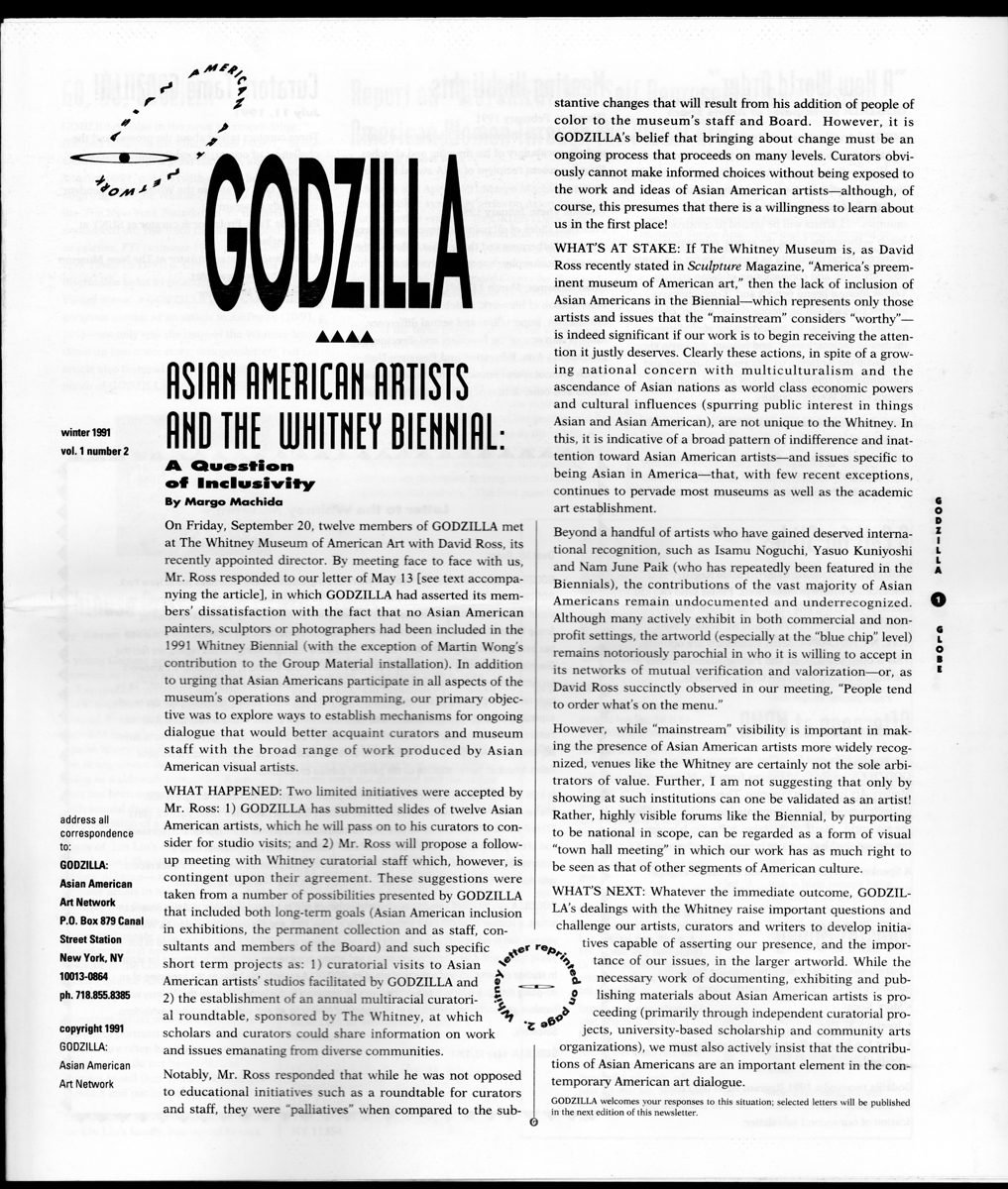

The group wasted no time, hitting an impressive stride early in its existence. In 1991, Godzilla wrote a forceful letter to David Ross, then the director of the Whitney Museum, denouncing the lack of Asian American artists at the 1991 Whitney Biennial. Ross agreed to meet with the group. After the conversation, Godzilla issued a follow-up letter. “As discussed, the regrettable absence of Asian American visual artists in the last Whitney Biennial remains symptomatic of a larger issue—the lack of awareness, or often even interest, among curators in many major institutions, of the numerous artists emerging from Asian American communities and their significant and growing contributions to the public discourse,” they wrote. “To remedy this problem, mechanisms must be established by which staff at the Whitney can become familiar, on an ongoing basis, with the rich range of work produced by Asian American artists.” Godzilla didn’t stop there. They arranged materials on a dozen Asian American artists and sent them to the Whitney’s curatorial staff, pointing out that all the artists were available for studio visits. Godzilla began attracting press. A 1991 piece in Art in America—titled “Guerilla Girls Move Over?”—talked about Godzilla and the group’s newsletter.

Godzilla worked to raise awareness of hate crimes against AAPI artists. In one example, a 1991 flyer included in the book advertises a candlelight vigil and protest dedicated to Lin Lin, an artist shot in Times Square while making portraits. Godzilla was involved with AIDS activism—for instance, Chu, who was also involved in ACT UP, wrote a proposal in 1990 for an Asian Pacific Islander AIDS Project, to be held at Art in General, which soon came to fruition. Godzilla also lambasted familiar Asian tropes, even when they came from other activist groups. (In 1991, Chu wrote a strongly worded letter decrying the Lambda Legal Defense Fund’s use of Miss Saigon in a fundraiser.) In 1995, an installation with the title “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles—NOT!” was mounted by members of the group.

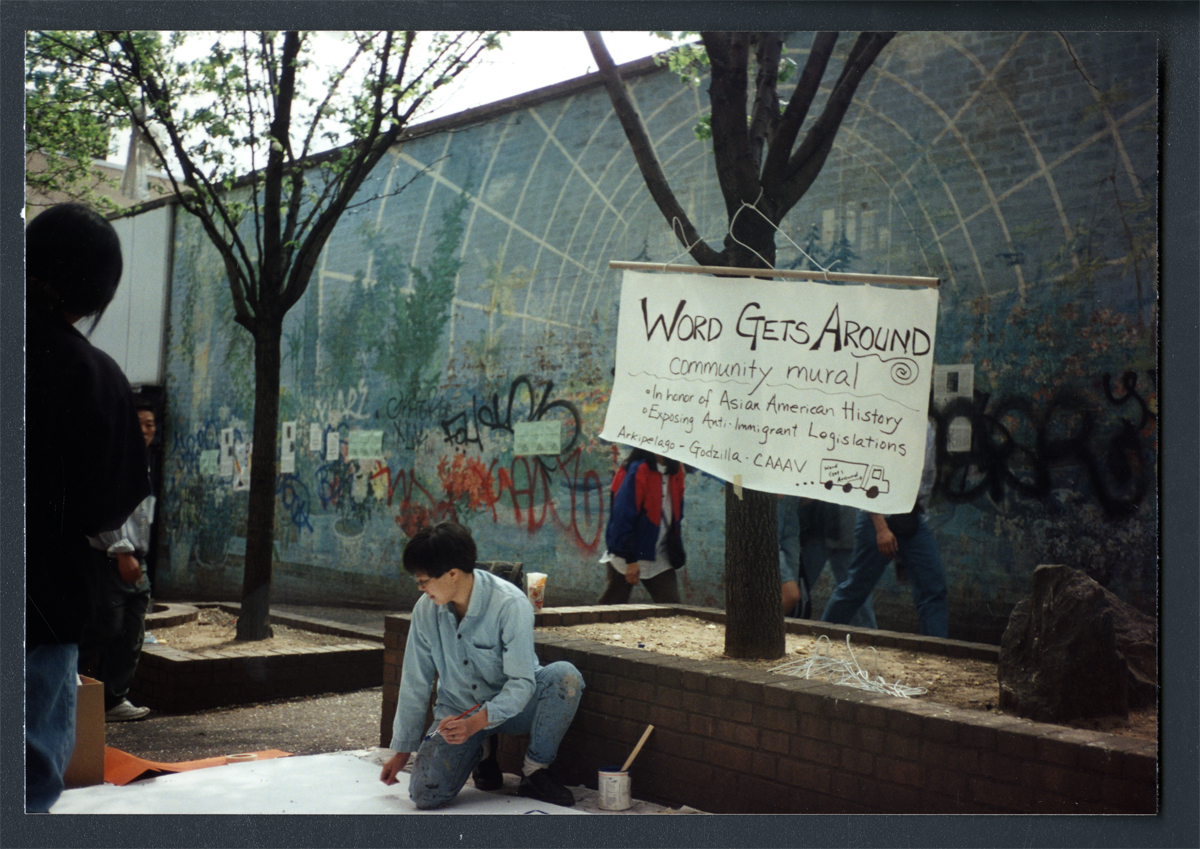

View of Word Gets Around, 1995, a community mural made in collaboration between Godzilla Asian American Arts Network Archive, Arkipelago, and CAAAV. Photo: Fales Library and Special Collections, NYU.

Godzilla’s heyday may have been the 1990s, but they still exist today, and their strong principles remain. Earlier this year, Godzilla withdrew from a planned retrospective at the Museum of Chinese in America, located in Manhattan’s Chinatown, in protest against the institution’s apparent tacit approval of a twenty-nine-story city jail to be constructed in the neighborhood, as evidenced by their acceptance of $35 million in city funds. “We cannot, in good conscience, entrust the legacy of Godzilla as an artist-activist organization to a cultural institution whose leadership ignores, and even seeks to silence, critical voices from its community,” the group wrote in a letter. Godzilla’s activism lives on.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including the Guardian, Wired, the Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.