Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Cochin Moon rises again. And so do four other reissued LPs by the experimental Japanese musician.

Taping for the TV show Young Impulse, July 1975. Image courtesy the Masashi Kuwamoto Archives.

Haruomi Hosono, Hosono House, Paraiso, Cochin Moon, Philharmony, omni Sight Seeing, Light in the Attic

• • •

Haruomi “Harry” Hosono is one of music’s foremost mad geniuses. Now seventy-one years old, he has had a furiously prolific career spanning five decades and dozens of startling albums. In 1978, he founded a group ahead of its time—the Japanese synthpop band Yellow Magic Orchestra, or YMO, with Ryuichi Sakamoto and Yukihiro Takahashi. He deserves to be a major figure not only in the history of Japanese music, but in popular music writ large.

YMO is sometimes compared to Kraftwerk, another group that famously merged electronics with pop music in the 1970s. Kraftwerk became a household name, but YMO remains oddly underrated—YMO was every bit as important as Kraftwerk, in their own unique way. “Even in the beginning of that time when we were doing YMO, of course we knew Kraftwerk, and we thought their music was so German,” said Sakamoto when I interviewed him in 2006. “It was conceptual, kind of theoretical, very focused, simple and minimal and strong . . . We wanted to make something very Japanese in contrast. It’s a very good contrast, Kraftwerk and YMO. YMO had a mixture of everything—American music influence, European music influence, classical influence, pop—so many. It’s like a bento box. And we thought that was very Japanese.”

With Yellow Magic Orchestra at Hurrah, New York City, 1979. Image courtesy Mike Nogami.

Five Hosono solo albums, newly reissued on vinyl for the first time outside of Japan by the Light in the Attic label—Hosono House (1973), Paraiso (1978), Cochin Moon (1978), Philharmony (1982), and omni Sight Seeing (1989)—offer a fascinating plunge into Hosono’s adventures outside of YMO. Hosono began playing music in the 1960s, as a founding member of the psych-rock band Apryl Fool. In the early 1970s, he was in a folk-rock group called Happy End. Listening to these reissues, you can hear his artistic development—his early folk roots; his kaleidoscopic sampling and electronic experiments as he gained new access to technology; the proto-techno, exotica, and pop of the YMO years; his travels through ambient sound.

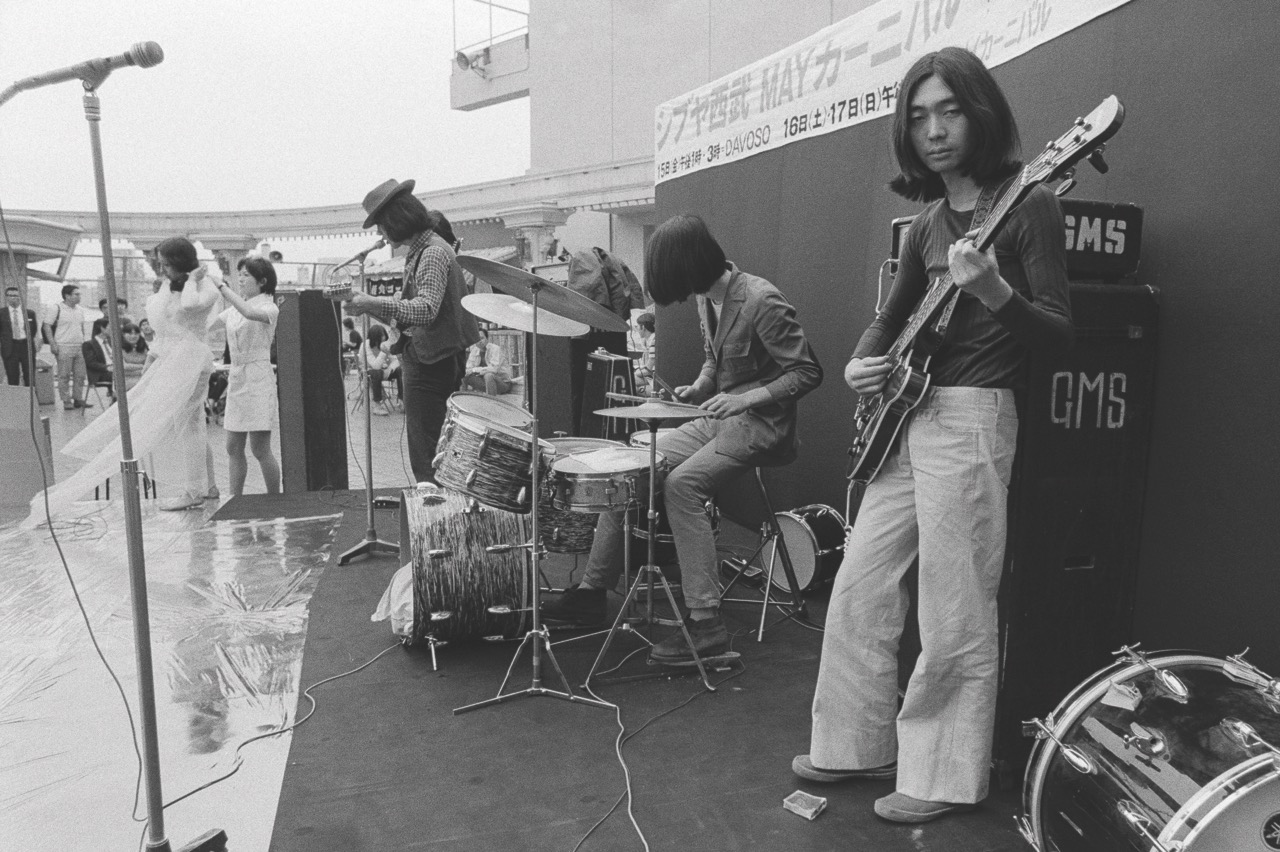

With Happy End, Shibuya Seibu May Carnival, May 16, 1970. Image courtesy Mike Nogami.

The introspective acoustic balladry of Hosono House displays a sensitive side of Hosono that listeners mostly familiar with YMO’s ecstatic jumble of beats may have never experienced. Stylistically, it’s a continuation of his folkie sound in Happy End. While it’s a tranquil and pleasant listen, it’s not the most instantly memorable. Hosono found his voice later in the 1970s, when he got deeper into electronic music.

Paraiso, festooned with electronics and released in 1978, holds special historical significance: the album led to YMO’s formation. As legend has it, Sakamoto, Takahashi, and Hosono first started YMO at Hosono’s house, the night after recording Paraiso. (The album was originally credited to “Harry Hosono and the Yellow Magic Band.”) “The ‘Yellow Magic Orchestra’ name was from Hosono,” Sakamoto explained to me in 2006. “He kind of invented that, from white magic and black magic. His idea was yellow was in between white and black. It’s kind of the average, to calm down the conflicts.”

Haruomi Hosono in Sayama, Saitama Prefecture, 1973. Image courtesy Mike Nogami.

Hosono was the crazy uncle and fiery radical of YMO, much like Holger Czukay in the great German group Can. Study old pictures of Czukay and Hosono and they even look the same, right down to the shaggy hair, handlebar mustache, and outlandishly colorful shirts. Like Czukay, Hosono played bass and a range of electronic gear. They both listened with open ears; they were both voracious consumers of what is now called “world music.” They both showed great ingenuity with sampling at a time before digital samplers became widely available. Czukay’s mind-altering tape-loop opus “Boat Woman Song,” from his prescient 1969 collaboration with Rolf Dammers, Canaxis, prefigured Hosono’s later experiments with sampling and electronic treatments.

Philharmony is the most overtly electronic sounding of all the Hosono reissues, an album of weird robot pop. On the back of the LP, Hosono lists all of his synth gear in detail—a nerdy move, to be sure. But Hosono went a step further to credit his gear as guest performers: a Linn drum machine, E-mu Emulator, Roland MC-4, and a Prophet-5 synthesizer rub shoulders with human collaborators. Philip Glass–style interlocking patterns, stuttering vocals, and tightly wound techno-funk swap places; the upbeat track “Platonic” would sound at home in a DJ set today. Omni Sight Seeing, a dazzlingly varied album of “world music” as interpreted by Hosono, includes a straight-up acid house track.

Hosono’s best-known solo album, Cochin Moon, was released as a collaboration with the noted pop artist Tadanori Yokoo. The hallucinatory, transfixing record was inspired by a trip they took to India in 1978. It was initially meant to be Yokoo’s project—Yokoo had been commissioned to do an album, according to the interview with Hosono in the liner notes, but Yokoo soon foisted the task on Hosono. Yokoo’s contribution instead was to craft the whimsical cover art, collaged from what looks like an array of hand-painted Bollywood movie posters. On the cover, a man and a woman gaze rapturously at each other inside a giant lotus, flanked by cheerful elephants; in the background, crimson drapes give way to a boy clinging to a palm tree, under a full moon.

Hosono started Cochin Moon by making some field recordings in India, but soon became violently ill. The album, created when Hosono came home with an ace team of collaborators including Sakamoto, keyboardist Hiroshi Sato, and tech whiz and future YMO “fourth member” Hideki Matsutake, speaks to this state of delirium and dislocation. “I had been transformed,” said Hosono in an interview about his trip to India. Some of the songs are richly redolent of Indian music, but it was synthesized in Japan. Cochin Moon is like music one would hear in a dream, or a distant memory—an album of plausibly Indian music, half-remembered and possibly misheard, filtered through the lens of a bewildered traveler. Some of the lilting melodies evoke traditional music played by street performers, but with harder edges and electronic effects. Hosono once discussed the similarities he felt existed between Kraftwerk and Indian music, and Cochin Moon is one of those odd nodes of connection. Four decades later, the album is still unmatched in its sumptuous strangeness.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.