Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

From martial arts to the science of tear ducts: a new documentary about the noted free-jazz drummer.

Milford Graves in Full Mantis.

Milford Graves: Full Mantis, directed by Jake Meginsky, co-directed by Neil Cloaca Young, screening at various locations through March 23, 2018. For full list: www.fullmantis.com

• • •

Speaking in Tongues, a 1982 documentary on the percussionist Milford Graves and the saxophonist and clarinetist David Murray, begins with a somber tale about John Coltrane’s funeral. Graves performed with the legendary saxophonist Albert Ayler at the event in 1967, the film announces solemnly. There is a cut to a desolate expanse of the East River, where Ayler’s drowned body was found in 1970. As fascinating as the documentary is, Graves is portrayed less as himself and more through his relationships to these famous dead musicians, in these historical moments frozen in time.

Milford Graves: Full Mantis, a new documentary directed by one of Graves’s students, Jake Meginsky, with co-direction by Neil Cloaca Young, is a dynamic portrait of the now seventy-six-year-old Graves, via observations of his life in his rambling, colorful Queens home, just down the street from the South Jamaica Houses where he grew up. No one else is interviewed but him; the documentary is focused entirely on the legendary drummer and his kaleidoscopically varied interests—herbalist, martial artist, musician, acupuncturist, scientific tinkerer. The feature-length film pulses with energy, and Graves talks a mile a minute, each sentence a mouthful almost more inconceivable than the last one.

Milford Graves in Full Mantis.

In a scene near the beginning of the film, Graves walks through his overgrown garden filled with herbs as cars zoom by. “Plants are constantly picking up cosmic energy, beyond photosynthesis,” he says. “To me they’re just like humans, man, you’re constantly breathing in air . . . we’re breathing all kinds of elements of nature. So what makes you think that plants are any different?”

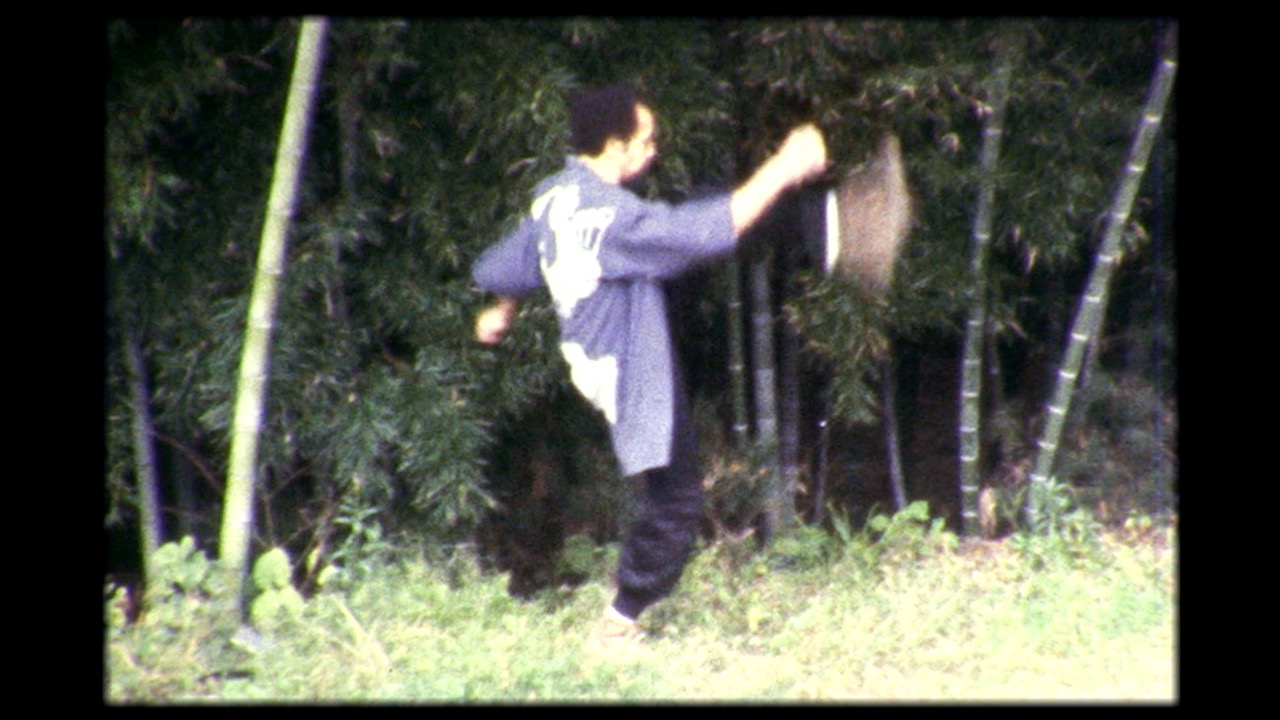

In another scene, he’s affixing electrodes to his torso, measuring EKG signals and animatedly discussing the connections between sound and the body. A few minutes later, he’s exuberantly demonstrating the martial art form he invented in the 1960s, which he calls yara, a word taken from the Yoruba language that means “nimbleness.” Graves set out to devise his own form of martial art, partly inspired by the moves of a praying mantis—hence the movie’s title. “I said I’m gonna go right to the praying mantis—that’s the boss, not some human,” he explains. “I watched them and I watched all their moves. I went to the best teacher.”

Milford Graves in Full Mantis.

His energetic and unpredictable patterns of conversation seem to parallel his approach to music. It is clear he doesn’t like following anyone else’s beat—nor does he follow a constant beat himself. A steady, repetitive rhythm, he says, is akin to death. “People say the best way to play in tempo is to get a metronome,” he says in the film. “Oh my gracious . . . too exact, too exact. But you know what? The body, the heart doesn’t have the same time length between each contraction and relaxation of the heartbeat . . . If the doctor heard that, and everything seemed to be clean, the more exact the time measures, the more dangerous it is.”

For a documentary about a musician best known as an icon of free jazz, there is little in the film that is explicitly about jazz. For much of Full Mantis, Graves isn’t playing music. He delivers numerous monologues, carrying the film with his undeniable charisma as he expounds on the science of tear ducts, his philosophy on gardening, or any number of other seemingly unrelated subjects. It becomes clear as the movie progresses that all of these disparate topics are part of his practice. Music is felt throughout Full Mantis, though, even when it isn’t being performed: in the rhythmic patterns of kicks and sparring of yara, in close-ups of the flowers in Graves’s yard fluttering in the wind.

Meginsky and Young’s thoughtful edits have their own internal rhythm, complementing Graves’s idiosyncratic flow. Graves, for his part, is a perfect fit for the screen, playing to the camera and clearly relishing being in the spotlight. He spent several decades teaching at Bennington College before retiring from there in 2012; he snaps quickly and easily back into a professorial speechifying mode, while also folding in the manic intensity of a martial arts master from a 1980s kung-fu flick.

Milford Graves in Full Mantis.

Some of the most spellbinding segments of Full Mantis involve black-and-white archival footage of a much younger Graves playing the drums with an epic ferocity. As LeRoi Jones—later known as Amiri Baraka—memorably wrote in 1966, Graves’s drumming “is great natural roars and chugs and stops and puffs and scrambling. Graves weaves and wheels in the back, the sound always changing. Never the quickly dull pre-felt tapping of the simply hip. The sound and sound devices, always changing, and the energy pushing it, unflagging.”

Full Mantis is a nuanced portrait of Graves, lovingly created from the perspective of filmmakers who are clearly major fans of his work. Meginsky and Young dispense with the usual tropes of music documentaries—the dry historical scene-setting, the airy pontificating from various talking heads—instead favoring a more disjointed approach, which succeeds in being both more provocative and more intimate at the same time. But perhaps hearing some other voices, outside of Graves’s own, would have helped to vary and develop the narrative. Shirley Clarke’s 1985 documentary Ornette: Made in America was imaginative and free-form, much like its subject, Ornette Coleman, but it took in other people, too, from Don Cherry to William S. Burroughs to Coleman’s son Denardo.

Full Mantis misses out on some of that potential for diversity of perspectives, but gains in its close understanding of the subject. The film plays like a ninety-one-minute private lesson from Graves himself. “What makes a person able to swing, versus not being able to swing?” he asks rhetorically at one point. “I’m not playing your typical dangadangadang . . . Swing, man, is getting you to move from one point to another point. It’s putting life into you . . . swing is when you can feel, man.” The film admirably depicts that feel—what happens not only in the notes of the music, but all of the spaces in between.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.