Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Speech as music: a rerelease of the composer’s mesmerizingly odd

Private Parts.

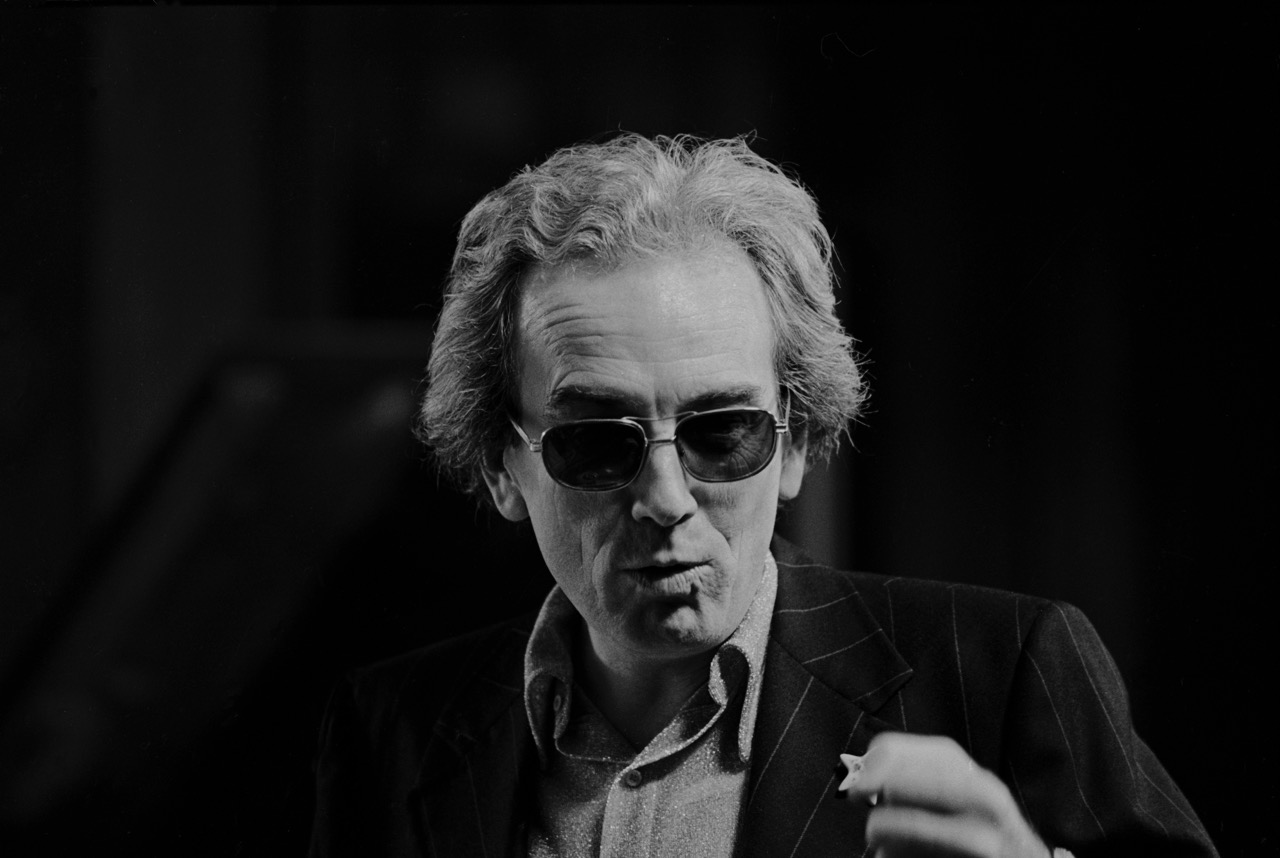

Robert Ashley, October 1975. Photo: Pat Kelly.

Robert Ashley: Private Parts, Lovely Music reissue 2019

• • •

No one sounded exactly like Robert Ashley. The storied composer, who died in 2014 at the age of eighty-three, reinvented opera. His works were not operas in any traditional sense; they were more like hypnotic multilayered monologues, often delivered against a backdrop of eccentric instrumentation. His librettos lacked conventional plot lines, using humdrum phrases and familiar patterns of the English language that disguised the emotional depth and complexity hidden underneath the surface.

In the world of experimental music, Ashley was an outlier too, standing as his own particularly weird genre. Fathoming this music meant upending all notions of what music is, and what it could be. There have been many composers who have coaxed listeners into questioning their assumptions—John Cage, to give one notable example—but Cage felt easier to study, in part because he left behind a wealth of writings that explained his methods.

Ashley was more of an enigma. It took me years of listening to him before it started to sink in. I remember seeing him perform his late-period opera Foreign Experiences at Mills College almost a decade ago, and the experience didn’t add up to me then. Ashley stood at the wooden podium in the concert hall, clutching a pile of papers in one hand and a glass of what appeared to be whiskey in the other. He read from the papers in a slow, thoughtful drawl, taking frequent breaks to drain his glass. The patterns of his mildly Midwestern-accented speech were almost soporific, rising and falling softly as he delved into a long, complicated story about a guy named Don. Of all the offbeat experimental music concerts I had been to at Mills, Ashley’s was the strangest. Over time, his music grew on me; Foreign Experiences was part of a long continuum of works that had turned opera on its ear. Ashley’s legacy was a colossal one. His body of work, while still curiously underrated, will continue to expand in significance in the years to come.

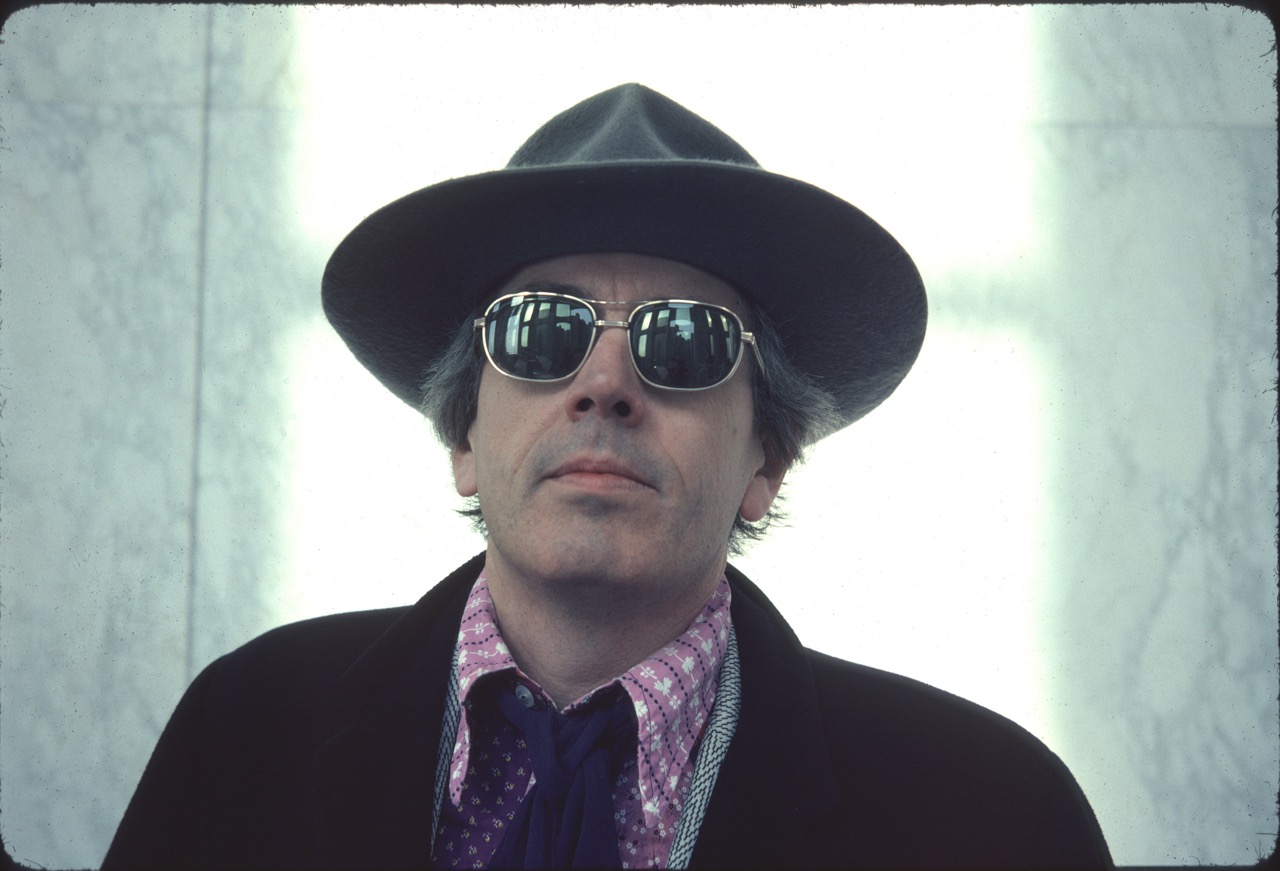

Robert Ashley, June 1976. Photo: Pat Kelly.

“Basically, Ashley regarded speech as music,” Alvin Lucier told me in 2014, when I was putting together an Ashley memorial for frieze. “I remember standing with him at gatherings after concerts in the Midwest, simply listening to people talking. He once remarked that, to his ears, the dull roar of many people talking was symphonic. Once as an accompaniment to a Merce Cunningham event in New York, Bob simply assembled a group of friends to sit on stage and have a conversation. There was no text, no instructions, no enhancements, no musical accompaniment. It was amazing just how riveting this experience was. One left the event wondering how Bob could have made this happen.”

The album Private Parts, originally released in 1978 and now reissued by Lovely Music, was a signpost for Ashley’s new way of making music. He had already been a composer for over twenty years by this point, writing left-field classics like the terrifying, noise-fueled The Wolfman (“Jaws dripping with feedback!” as Pauline Oliveros memorably described it to me), cofounding the Sonic Arts Union with Lucier, David Behrman, and Gordon Mumma, and the now-legendary ONCE Festival in Ann Arbor. Private Parts is as mesmerizingly odd four decades later as it was then; the only music it closely resembles is other work by Robert Ashley. Parts of it would resurface in his masterpiece Perfect Lives, a video opera structured as seven half-hour television episodes, which aired in the 1980s on Channel Four in Britain.

Side 1 of Private Parts, “The Park,” is an extended meditation centering on a man alone in his hotel room. On side 2, “The Backyard,” a woman muses about her past while standing in her mother’s house. Ashley coolly describes mundane details of the hotel, speaking at the threshold of audibility. “And all rooms were not the same / Some better than others, he thought / A better view, a better layout / Better shower, softer bed / Not so far from noise, more like home.” A bit later: “Room service courtesy of the company.” It meanders like this, slowly unfolding into a forlorn, melancholy portrait of a man. On side 2, Ashley offers numbing suburban details (“She gets catalogues of every sort in the mail”), that slowly develop into richly hued descriptions that seem almost accidentally beautiful (“Sundown, one, the time it disappears / Gloaming, two, the twilight, dusk / Crepuscule, the twilight, three, the half-light / Twilight, four, pale purplish blue to pale violet, lighter than dusk blue . . . Clair de lune, five, greener and paler than dusk.”)

Ashley’s voice on the album is given some forward propulsion by the thrumming of a tabla (played by the noted sitarist Krishna Bhatt, credited on the album as “Kris”). Ashley’s longtime collaborator “Blue” Gene Tyranny offers light and effervescent cocktail-piano flourishes and delicate synthesizer washes. It all amounts to a peculiar musical arrangement, to say the least. Every sonic element is low in the mix. Ashley’s voice doesn’t take center stage; it’s just one of the other instruments. In that way, Private Parts is a lot like ambient music. It’s music, to quote Brian Eno, that is “as ignorable as it is interesting.” Ashley’s words are almost imperceptible, even when blasted at top volume. To cite his own lyrics, from side 1, “There was something like the feeling / Of the idea of silk scarves in the air.”

Robert Ashley, 1975. Photo: Mimi Johnson.

Many of Ashley’s contemporaries also worked with speech. Lucier fused room resonances with repetitions of his voice in his 1969 classic “I Am Sitting in a Room.” Steve Reich’s early tape pieces “It’s Gonna Rain” (1965) and “Come Out” (1966) made music out of inventively looping and phasing samples of speech. Their work transformed patterns of words into sound art and experimental music, but Ashley dealt with language most fully on its own terms. He reveled in the often dull, prosaic nature of communication, the run-of-the-mill American accents, and the seemingly banal narratives of ordinary people in small towns. It is music that is about nothing at all, and about everything at the same time.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist specializing in twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.