Geeta Dayal

Geeta Dayal

Machine-made epic: A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound is fourteen hours of cybernetic music.

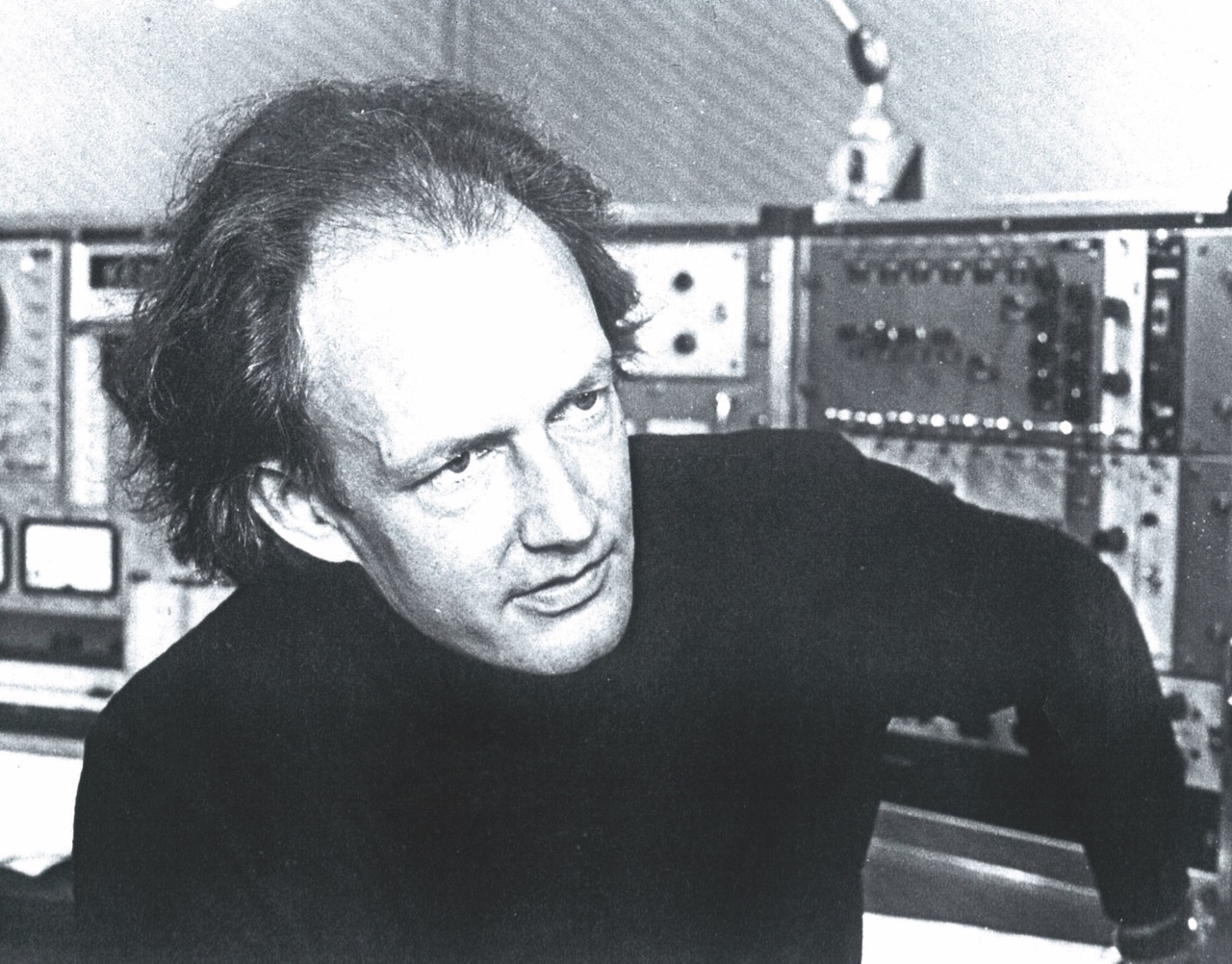

Roland Kayn. © LRKA (Lydia-und Roland-Kayn-Archiv).

Roland Kayn, A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound, frozen reeds

• • •

The history of electronic music in the twentieth century is crammed with wildly idiosyncratic personalities—and an equally wide range of machines, methods, and philosophical approaches. But even within that rarefied realm of frequently enigmatic figures, the late composer Roland Kayn is lesser known, and his work remains mostly obscure—as if by design.

Kayn was born in Germany in 1933 and moved to the Netherlands in 1970. In the 1960s, he spent a stint with the noted Italian experimental collective Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, but abandoned the spirited group for a more hermetic existence in Utrecht, at a sonic laboratory known as the Institute for Sonology.

Kayn described much of his beguiling body of work—collected on a series of cryptic releases with titles like Tektra, Infra, and Simultan and packed with intricate, technical liner notes—as “cybernetic music.” Inspired, in part, by his mentor Max Bense’s teachings on “generative aesthetics” in the 1950s, Kayn developed a method of composing music without specifying everything from the top down—a different approach from, say, Kayn’s more famous German contemporary Karlheinz Stockhausen, who favored tight control over his compositions. Kayn devised analog systems that could be steered to create intriguing new pieces of music.

Roland Kayn. © LRKA (Lydia-und Roland-Kayn-Archiv).

Kayn wasn’t the first electronic musician to claim inspiration from cybernetics. The American composer couple Louis and Bebe Barron also worked to create a sort of cybernetic music before him, beginning in the early 1950s, and routinely cited Norbert Wiener, the father of modern cybernetics, as an inspiration. The pair was most famous for the revolutionary score for the 1956 science-fiction classic Forbidden Planet. Working out of their Greenwich Village apartment, the Barrons crafted their own makeshift electronics—in their words, “individual cybernetics circuits for particular themes and leitmotifs.”

Though Kayn and the Barrons both used some similar language to describe their works, they made radically different music. The Barrons excelled at making exquisite miniatures—in their tightly arranged scores for short films in the early 1950s, or in the peculiar sonic circuits they customized to Forbidden Planet’s characters, which they recorded onto tape and meticulously edited to match the film. Kayn’s methods were more esoteric and theoretical, and the voluminous fields of sound his systems generated could stretch on for hours—slowly changing in ways that feel somehow transcendental.

Album cover art for A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound. Image courtesy frozen reeds.

An epic Kayn work titled A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound, recently released by the frozen reeds label in Finland, is nearly fourteen hours long. The recordings were painstakingly restored over several months by the musician Jim O’Rourke, and Kayn’s opus is now available as a mammoth sixteen-CD box set, in an edition of 750.

In the wild spaces of A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound, there are few conventional melodies, harmonies, or rhythms. Notes hang in midair and expand slowly, into huge luminous clouds. In the track “Somitoh”—which is fifty-three minutes long—one experiences craggy waves of harsh buzzing, long glassy tones, static, and graceful sections that sound almost orchestral, like violins. “Ykties” has passages that lend the impression of crickets at night, followed by rippling sheet metal, a plane lifting off, and a chorus reverberating in a massive cathedral.

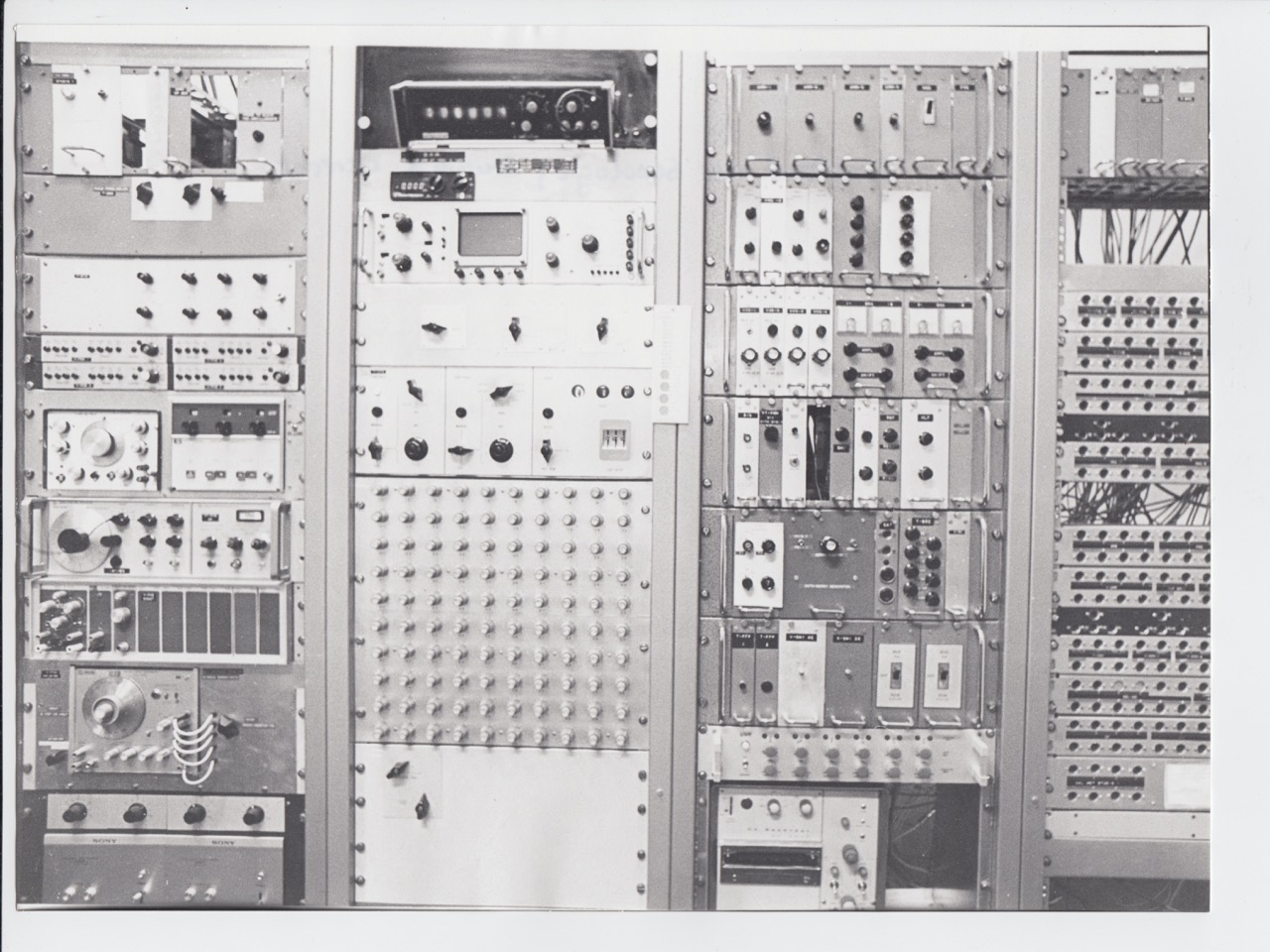

© LRKA (Lydia-und Roland-Kayn-Archiv).

All these effects, of course, were made by an inscrutable network of machines—but they conjure potent images. You fill out Kayn’s uninhabited spaces with your imagination. Often, the music has a dark, eerie undertow. One has the sensation, when hearing Kayn, of being a lone explorer in a strange world. Picture traversing an icy cavern, or wandering through a dense, vaporous fog at night that extends in all directions, forever.

Kayn originally created the pieces on A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound over the course of several years at the Institute of Sonology, aided by his longtime engineer, the Dutch composer Jaap Vink. Kayn combined them much later into a lengthy broadcast for Dutch radio in 2009, two years before his death. Several of the pieces—with angular titles like “Tachys,” “Czerial,” and “Xattax”—are nearly an hour long, and it’s often hard to tell where one piece stops and the next begins.

Roland Kayn. © LRKA (Lydia-und Roland-Kayn-Archiv).

How does one focus on a work that is almost fourteen hours long? In a culture so accustomed to three-minute singles, and perpetually clicking around to different streams and YouTube videos, finding the time for a seventy-minute album these days takes planning. A fourteen-hour album is a major event. Even with the MP3s, I found myself suffused with a new degree of respect for Kayn after having to spend an entire afternoon clearing out space on my hard drive just so I could download the colossal suite of recordings.

For the past month, A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound was the soundtrack to my life. Listening to it in full requires putting it on in the morning, and turning it off before bed, to the exclusion of all other recorded music. In the raw early daylight, at low volume, it worked well as a soft ambient tint to the air—mixing seamlessly with the loud hum of the espresso machine, with the chirps of birds, the rush of cars and street noise. Later on, as darkness fell, Kayn’s music gave the feeling of growing more intense and foreboding, shaping the everyday experience of nighttime into a grander, more meaningful arc.

After several hours of immersion in Kayn, one begins to transition into a more sensitive and receptive mode—becoming hyper-attuned to small contrasts, as subtle sonic shifts transform into vast chasms. Music that appeared to be monochromatic at first glance takes on delicate shadings in blue, gray, and green.

While listening to Kayn one night, I was reminded of a particularly evocative Brian Eno song title from his 1977 album Before and After Science, called “Through Hollow Lands.” On A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound, there is a profound awareness of time and immensity, on the macro and the micro scale. Kayn’s work vibrates through hollow lands—in unfamiliar terrain with bottomless depth.

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist, specializing in writing on twentieth-century music, culture, and technology. She has written extensively for frieze and many other publications, including The Guardian, Wired, The Wire, Bookforum, Slate, the Boston Globe, and Rolling Stone. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno (Bloomsbury, 2009), and is currently at work on a new book on music.