Mark Dery

Mark Dery

The radical visionary who created a psychotherapeutic

collective in Vichy France.

Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut, installation view. Courtesy American Folk Art Museum. Photo: Eva Cruz, EveryStory.

Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut, curated by Joana Masó, Carles Guerra, Valérie Rousseau, and Edward Dioguardi, American Folk Art Museum, 2 Lincoln Square, New York City, through August 18, 2024

• • •

Decades before the anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s, when the psychiatrist R. D. Laing and the psychoanalyst Félix Guattari reimagined schizophrenia as a response to a dysfunctional society whose “norms” were a straitjacket for the mind, the avant-garde psychiatrist Francesc Tosquelles (1912–94) created a psychotherapeutic collective. At the Saint-Alban psychiatric hospital, which he directed during World War II, the cordon sanitaire between doctor and patient, “sane” and “mad,” was deliberately blurred.

That he did so in Vichy France is nothing short of miraculous. The collaborationist regime’s official policy toward the cognitively disabled (“life unworthy of life,” in the sinister Nazi parlance) was l’extermination douce (“soft extermination”): forty thousand patients were starved to death (rather than shot, gassed, or killed by lethal injection, as in the Third Reich). There was nothing “soft” about it: “Patients were chewing their fingers off,” a doctor recalled. “They dreamed of nothing but food.” Saint-Alban’s location spared its residents that piteous fate: tucked away in the isolated village of Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, in a mountainous stretch of central France, it escaped bureaucratic notice.

Photographer unidentified, Aerial view of the Saint-Alban psychiatric hospital, Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, France, ca. 1960. Postcard. Courtesy American Folk Art Museum. Photo: Baldran Collection.

Tosquelles’s first order of business, when he took charge of the hospital in 1940, was ensuring its 850-plus patients survived the war. Yet even while he was hoarding food against the ever-present threat of famine—and hiding members of the Resistance; Jews in flight from the Nazi terror; and artists and writers like the Dadaist enfant terrible Tristan Tzara and the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard, whose anti-fascist politics or “degenerate” modernism had earned them the unwanted attentions of the authorities—he pursued his radical vision of a psychotherapeutic community.

Photographer unidentified, Hospital staff with their children and patients during a day trip near Saint-Alban, Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, France, ca. 1950. Courtesy American Folk Art Museum. Photo: Baldran Collection.

Tosquelles believed psychiatric institutions must be cured of their repressive tendencies, an approach later dubbed “institutional psychotherapy.” At Saint-Alban, the traditional pyramid of power relations, with the men in white coats at the top, was flattened. Off came the white coats—literally. Decision-making was collectivized in a cooperative structure in which doctors, staff, and patients deliberated as equals. Many aspects of the patients’ daily lives—therapeutic workshops, theatrical performances, parties—were managed by the patients themselves. Tosquelles’s theories owed something to Marxism (a Catalan, he fought with the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification during the Spanish Civil War); something to the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who questioned the assumption that it was possible to draw a bright line between normal and pathological; something to the German psychiatrist Hermann Simon, an early advocate for involving patients in the everyday workings of an institution. Playing a valued role in the hospital’s micro-society was its own sort of therapy, Simon discovered, reducing the need for sedation or isolation.

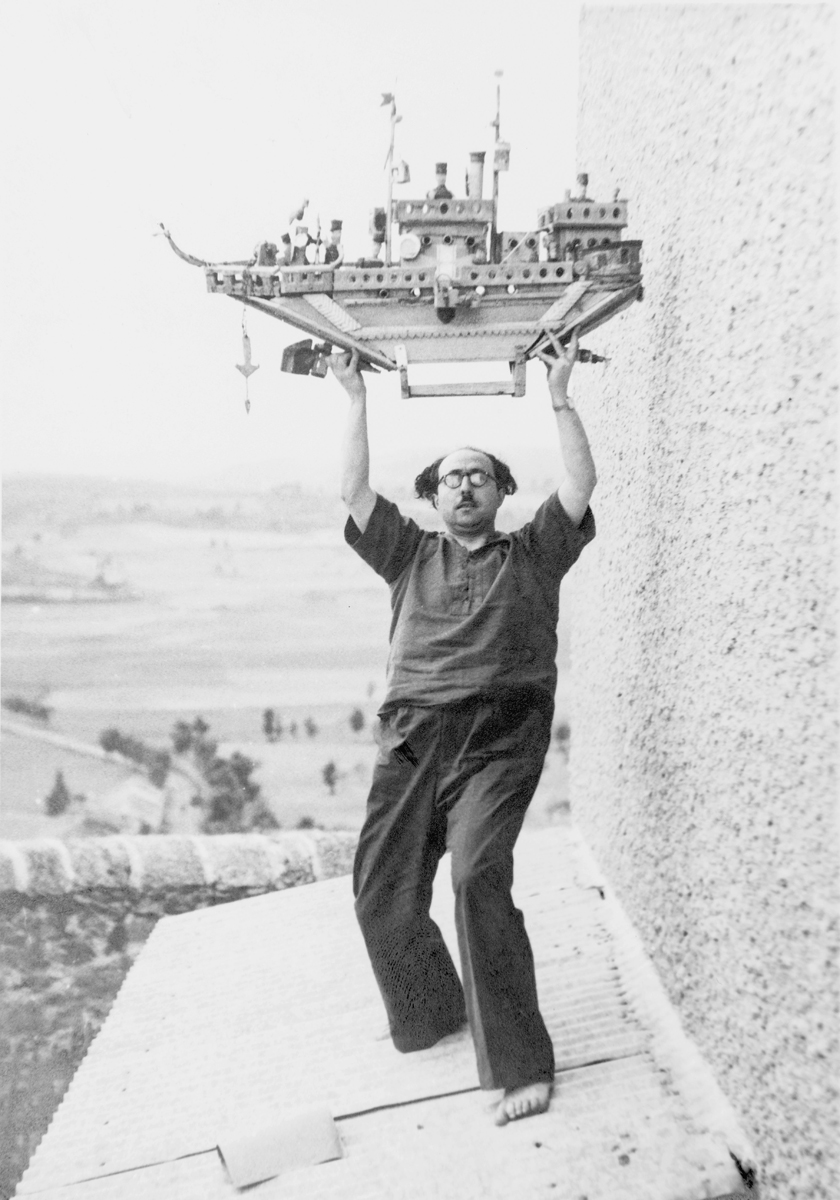

Romain Vigouroux, Francesc Tosquelles on the Roof of a Building at the Saint-Alban Psychiatric Hospital, Holding a Sculpture by Auguste Forestier, 1947. Gelatin silver print, 7 × 4 7/8 inches. © Roberto Ruiz.

A toy ship on display in the American Folk Art Museum’s enthralling show on Tosquelles and the origins of art brut is emblematic of his Simon-ian emphasis on self-directed therapy through creative, occupational, and social activities. Cobbled together from bits and bobs of metal and wood, it’s the handiwork of a patient named Auguste Forestier. Forestier’s whimsical folk-surrealist creations, like the works of his fellow residents in the asylum-village, were regarded not so much as “artworks,” notes cocurator Carles Guerra, but as “objects that had exchange value” when sold as toys or gifts to the nearby villagers. Profits from the sale of the patients’ art, split between the artist and the collective, “contributed to the hospital’s economy during a time of severe rationing,” a wall text informs, but “also became a means of repairing broken connections to others.”

The most mind-boggling revelation in the AFAM show is Tosquelles’s erasure from art history until the 2022 exhibition Francesc Tosquelles: Like a Sewing Machine in a Wheat Field (a collaborative endeavor sprawling over four venues in Spain and France, most notably the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, in Tosquelles’s native Catalonia; the AFAM version is abridged to fit the museum’s vest-pocket space). In addition to Éluard and Tzara, the French playwright Antonin Artaud, inventor of the “theater of cruelty” (who suffered from mental illness himself) and the Antillean psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, author of the anti-colonial classic Black Skin, White Masks, passed through Saint-Alban. (Fanon worked with Tosquelles as a resident doctor from 1952 to ’53. In Algeria, during the War of Independence, he applied what he’d learned at Saint-Alban to his attempt to practice an anti-colonial psychiatry.)

Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut, installation view. Courtesy American Folk Art Museum. Photo: Eva Cruz, EveryStory. Pictured: Auguste Forestier, Untitled, no date. Wood and nails.

Éluard brought some of Forestier’s sculptures back to Paris, where they captivated his fellow avant-gardists. The painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet was especially taken with them; in 1945, he made a pilgrimage to Saint-Alban to purchase objects by Forestier and others. Their work crystallized Dubuffet’s emerging vision of a “raw art” (art brut) “uncontaminated by artistic culture”—unmediated expressions of the creative impulse whose naïve, self-taught style and “uncivilized,” visionary, or psychedelic subject matter delivered a revivifying jolt, he thought, to an overcivilized art world. Graffiti was art brut. So were children’s art, prisoners’ art, and, above all, the art of the insane.

Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut, installation view. Courtesy American Folk Art Museum. Photo: Eva Cruz, EveryStory. Pictured: Jean Dubuffet, The Master of Ceremonies, 1955.

Tosquelles and Dubuffet circled warily, staking out the positions that would define the debate over Outsider art, as it came to be called. “Tosquelles initially greeted Dubuffet’s collecting initiatives with skepticism, seeing him as an aesthete looking to commodify works that emerged as by-products of patients’ psychiatric treatment,” a wall text reports. He “had no interest in the countercultural sensibilities of Dubuffet’s art brut.” Dubuffet returned the compliment, dismissing psychiatry’s “emphasis on the ‘rehabilitation’ of artistic patients” as “part of a larger scheme of exploitation underlying the field of ‘psychopathological art.’ ” Another text adds, “With the notion of art brut, Dubuffet aimed to broaden the art-historical canon, emphasize the singularity of a given creator’s perception of reality, and separate these works from psychiatric stigma.”

Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut, installation view. Courtesy American Folk Art Museum. Photo: Eva Cruz, EveryStory. Pictured, far left: Brassaï, Graffiti; The Birth of the Face, Belleville Paris, Series III, 1952. Silver print laminated on hardboard.

Diagnostic tool, grist for the psychoanalytic case study? Or work of art, better suited to the critical gaze? And what about the pieces in Francesc Tosquelles inspired by the folkish or “primitive” style of art brut, such as Dubuffet’s Master of Ceremonies (1955), a mutant deity conjured from “imprints in India ink glued on cardboard”? Or modernist attempts at seeing the world through Outsider eyes, as in Brassaï’s Birth of the Face (1952), a photo of a wall whose pocks and cracks seem to resolve themselves into an apparition peering back with black-hole sockets?

Auguste Forestier, Untitled (Rooster), 1935–49. Wood and metal, 10 5/8 × 11 3/8 × 13 inches. Courtesy American Folk Art Museum.

You’ll restage this debate in your head as you wander through this overstuffed curiosity cabinet of a show, marveling at Forestier’s comic-grotesque carving of a rooster-man with a cockscomb fit for an Aztec deity (Rooster, 1935–49); Artaud’s scribbly, Basquiat-like drawing, The Revolt of Angels from Limbo (1946); and the embroidered wedding dress (1944–55) knitted by Marguerite Sirvins from threads unraveled from hospital bedsheets. Sirvins, who was somewhere between fifty-four and sixty-five at the time, believed she was eighteen, a doctor recalled, and would “marry a suitor of her choosing” when she “came of age.”

In the psychological debris field left behind by the war, several of Saint-Alban’s schizophrenic patients were haunted by what Tosquelles called a “delusion of the end of the world.” “While these delusions shared many of the hallucinatory characteristics of psychosis,” a wall text observes, “they also appeared to manifest as responses to political events.” Now, with the mass sociopathy of fascism resurgent and Gaza, Ukraine, and Sudan drowning in a flood tide of horror, their visions, still transmitting from an asylum that offered refuge from murderous unreason, may have something to teach us.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and the author of four books, most recently, the biography Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. He has taught journalism at NYU and “dark aesthetics” at the Yale School of Art; been a Chancellor’s Distinguished Fellow at UC Irvine, a Visiting Scholar at the American Academy in Rome, and a fellow at Hawthornden Castle near Edinburgh; and published in a wide range of publications.