Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Memories, speak: in a novel by Monika Zgustova, the story of Véra and Vladimir Nabokov’s marriage, and the fallout of an early affair, is triangulated through a prism of perspectives.

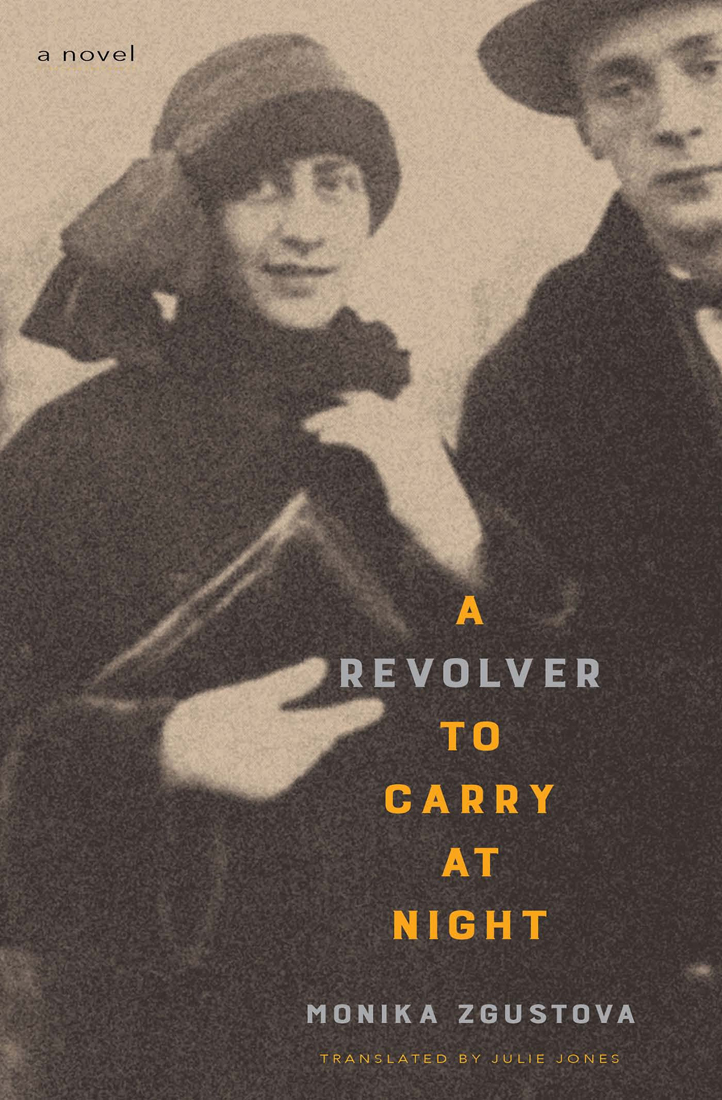

A Revolver to Carry at Night, by Monika Zgustova, translated by Julie Jones, Other Press, 150 pages, $15.99

• • •

“I am always there, but well hidden,” Véra Nabokov once said of her presence in the novels of her husband, Vladimir. It was she who typed and retyped his manuscripts from the famous index cards, negotiated with uppity publishers and journalists, and in general managed the silky reputation and rigorous writing schedule that made him so happy. (Has a novelist ever been quite so boyish and buoyed at his own achievements?) Véra was there at his lectures when he first taught in the US, an enigmatic assistant and even his stand-in when the charmer was indisposed. He couldn’t type, drive, or make a cup of coffee. As Jenny Offill puts it in Dept. of Speculation, “Nabokov didn’t even fold his umbrella. Véra licked his stamps for him.” In Monika Zgustova’s short but ambitious novel, A Revolver to Carry at Night, the marriage of Véra and “Volodia” is at the center of a larger narrative about hiding and revealing, guilt and control, troubling memories of former bliss.

It’s apt that the story of this couple, happy and unhappy exiles in language as much as geography, should be told by a Czech novelist writing in Spanish, here translated into English by Julie Jones. According to Nabokov himself, the lapsed-aristocrat writer met the fellow-Russian, Jewish publisher’s daughter at a ball in Berlin in May 1923—she was wearing a Venetian wolf mask, and later recited some of Nabokov’s own verses at him. They married in 1925. A Revolver to Carry at Night discovers them fifty-two years later, living at the Montreux Palace Hotel in Switzerland; Nabokov is nearing eighty, his health failing, but he is still at work on a final novel, The Original of Laura. In between: their flight to Paris and onward to America, the writer’s struggle to move from his merely fluent English to an achieved literary style, the artistic and commercial triumph of Lolita in 1955, and a return to Europe as lofty, perhaps a little vulgar, literary celebrities.

Zgustova recounts such events and tendencies mostly in passing, drawing on biographies and letters as well as Nabokov’s novels. At times, though, the bare facts sit awkwardly, like so much Wiki-précis, alongside the more fundamental emotional content of the novel, which is vexed and vivid. In 1977, there are many things for Vladimir and Véra to recollect from their haven of lakeside light and luxury. A narrow escape out of Paris before the Germans arrived in 1940. (Nabokov’s beloved butterfly collection was thrown in the street by a Nazi search party, but many of the broken wings were miraculously returned to him after the war.) The death in a concentration camp of Nabokov’s brother, Sergey; in Zgustova’s telling, the novelist is burning with shame at having condemned Sergey for being gay. But as you might expect with Nabokov—a writer for whom sexual nostalgia sometimes seems a keener pain than grief—the real drama here has to do with a distant affair, and its afterlife in the Nabokov marriage.

In Paris in 1937, Nabokov had a brief liaison with Irina Yurievna Guadanini. When he confessed to Véra in Cannes later that year, Irina was suddenly also there on the seashore, tormenting all concerned. Nabokov chose to stay with his wife. The more cynical view of their marriage, which Zgustova veers close to, is that Véra’s solicitousness for the next forty years was nothing but a subtle revenge on her husband for this one betrayal. She was present at his lectures on Russian literature at Wellesley and Cornell not from devotion but to shoo off the dreamy coeds. A Revolver to Carry at Night is divided into four chapters: the first three from the perspectives in turn of Vladimir, Irina, and Véra, the fourth involving all, as well as the Nabokovs’ son, Dmitri. In the Véra section, she comes across as a legendary conniver and lover of the good life, with a revolver in her purse: a habit from the precarious Paris days. (What is much less clear, aside from a description of Véra replacing Nabokov’s adjectives with better ones, is how she conceived of their literary collaboration.)

From some of this, you may get a sense of aspirant-Nabokovian complexities and atmospherics, if not actual verbal or syntactic felicity. It is possible that in English Nabokov is the most dangerous prose writer to try and emulate, because his merits—a slinkiness of sentence, arch wit, exquisite eye, and erotic charge about anything at all—come so close to mannerism, or kitsch. (More than once, starting to write a book, I have had to hide my copy of his too-tempting autobiography, Speak, Memory.) For the most part, Zgustova wisely avoids trying for Nabokov’s roundabout and multi-clausal seductions, but she might have been better off banning figurative language entirely. Here is Véra about Irina: “The girl was as supple as a serpent, as sensual as a cat.” Hard to believe that Véra is both the surreptitious improver of her husband’s style and the perpetrator of those similes. Or the mixed metaphors in Dimitri’s description of his mother: “her skin as white as snow, on which time had engraved its delicate designs like the ice on glass windowpanes.”

Prose texture aside, there are some quite glaring instances of needless exposition in Zgustova’s dialogue. In 1977, Vladimir demands that Véra destroy The Original of Laura after his death—it was eventually published in 2009—and cites Max Brod’s rescue of the works of his friend Franz Kafka: a case Véra would surely have known decades earlier, and which in any case seems a bit of pedantic point-driving by Nabokov. We’re told that Nabokov “scandalized” the literary world by calling Virginia Woolf’s Orlando a piece of poshlost, or kitsch; but, in fact, he did so in a private letter to the Russian novelist Zinaida Shakhovskaia. At such moments, it seems Zgustova’s research and—appended, but maybe undigested—reading list has got the better of novelistic imagining. The most successful chapter is the relatively compact “Irina on the Beach,” which, because more speculative about her perspective, is also less schematic or familiar, and attends to the details of bodies and gazes and attendant emotions. Here, you can start to picture or to hear a novel that never names Nabokov at all but does justice to the “experienced handful” (per smarmy Martin Amis) Irina, unhidden at last.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities, Suppose a Sentence, and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on a book about Kate Bush, and another on aesthetic education.