Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

The return of an overstuffed mind: Lynne Tillman’s 2006 novel

gets reissued.

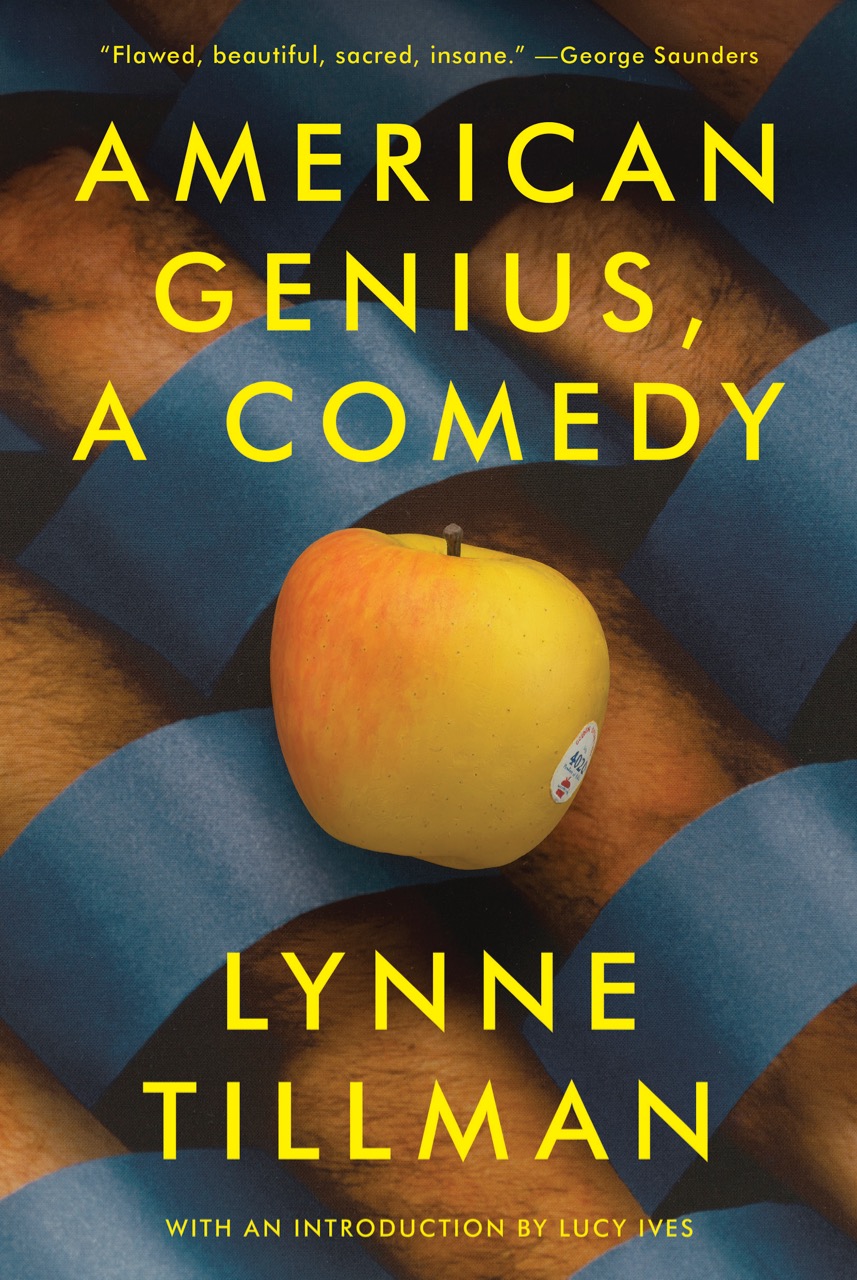

American Genius, A Comedy, by Lynne Tillman, Soft Skull Press,

359 pages, $16.95

• • •

“More and more, I want the freedom to be arbitrary,” says the narrator of Lynne Tillman’s fifth novel, American Genius, A Comedy, first published in 2006 but now happily back in print. Tillman leaves her protagonist unnamed until two-thirds of the way into her garrulous monologue, and although the name adds almost nothing, its delayed arrival is apt. This is partly a novel about knowledge (or is it mere information?) and how much of life’s friction—illness, grief, sexual disappointment—it may adequately distract us from. That the answer, predictably, is not much is nearly beside the point. Tillman gives us a mind hilariously on fire with compensatory distractions, bristling with facts that may not help at all. It’s a predicament she returned to, with a male narrator, in the novel that followed, Men and Apparitions (2018); but the earlier book is more engagingly odd.

Plot-wise, certain other essential details remain mysterious. The woman in question has admitted herself, voluntarily, to some kind of institution. Sanatorium? Asylum? Spa? Or artists’ colony? Perhaps she is simply describing one of these as if it’s another, and it takes only a subtle derangement of emphasis to see an obsessive patient as diligent researcher, or a staged performance about Kafka as product of florid delusions. Wherever the narrator has fetched up, it affords her leisure to fixate on her fellow residents’ eccentricities, and to reflect fitfully on her family: her deceased father, her mother who’s suffering from dementia, a brother likely homeless in Cincinnati or Mexico City. All of it, past and present, fills her with anxiety: “Everything is a problem in some way, I can’t think of anything that’s not a problem.”

The woman’s mind spins, and with it a voice that’s ardent and ironic, knowing and oblivious, repetitive and contradictory. In a novel that’s all voice, all of the time—at the near-ruinous expense of plot—the matter of style dominates. American Genius, A Comedy is full of long sentences that aspire to complex elegance but keep unraveling into run-on clauses, a perpetual and another thing. . . . Here’s the fretful narrator on the subject of socks, and much else:

I buy one hundred percent cotton socks whenever I can, though often there’s just a mix of eighty percent cotton and twenty percent nylon around, so I’ve mastered wearing this combination, adjusted to it, since it’s healthy to be flexible, but many people aren’t, and I, too, in my mind or especially my body, where habit and rigidity shape demands and inclinations, sometimes can’t exhort myself to the plasticity or fluidity I know is good for my health, and often I think few would survive if war came and deprived them of what they thought was necessary.

On and on she goes like this, she’s never found a comma splice she doesn’t like. You can’t really call this mode digressive, since it’s all Tillman gives us, or gives her character: a sensibility that catches on every stray burr of information, a brain with too many browser tabs open at once. She holds forth, among other things, on the Eames chairs of her childhood, and chair design in general; the Zulu language, which she is learning; Charles Manson’s acolyte Leslie Van Houten, her crimes, motivation, and bids for parole; the histories of silk and denim, which she has heard from her textile-merchant father. “I’m a recorder” and “a good listener,” she tells us. The amassing of facts—also grammar books, how-to manuals, biographies of criminals and philosophers—gives her a feeling of safety. From what? The unfathomable ways of her fellow residents, for sure: the “demanding man” who appears at breakfast, a psoriatic woman who will not shut up about her own problems. But also against life, the modern version of it. “Today, because of greater sensitivity, many people consider themselves sick, at risk, or threatened.” Because of greater sensitivity, or because they’re all drenched under the same always-open info-sluice?

Sickness, real or imagined, is one of the novel’s consistent, joco-serious, themes; it begins with an epigraph from JFK: “Life is unfair. Some people are sick, and others are well.” The narrator has been treated for a mundane catalog of mostly minor skin complaints: “seborrheic dermatitis; dilated blood vessels or telangiciectasias; benign growths, or seborrheic keratoses; solarkeratoses, or sun damage; skin tags; acne rosacea; xeroderma”—and so, itchily, shamefully, on. Ailing or disfigured skin—temporarily soothed by her Polish beautician, or cured by her dermatologist—is the narrator’s, and the novel’s, guiding metaphor. Anxieties erupt, childhood traumas, as cliché has it, come to the surface: “skin lets us know that a surface often isn’t superficial.” But there’s also a kind of perverse, extravagant pleasure in Tillman’s descriptions of the character’s suffering, as if the skin can only be soothed by lavish syntax or luxe vocabulary: “My skin seethes with vermiculations, which promiscuously derange my body.”

What kind of “comedy” is this? (Tillman’s title matters, with its unusual comma: the phrase A Comedy is not a subtitle, but something like one of her narrator’s addictive run-ons.) The comedy, surely of a sort of late modernism, familiar from Samuel Beckett and Thomas Bernhard: novelists whose narrators simply can’t be quiet, but find themselves yammering away, the brain always buzzing, dry lips smacking and teeth clacking as their stories and theories and opinions come tumbling out. Annie Dillard once referred to them as “crank narrators”; they don’t just have tales to tell, they know stuff. And want us to know it. It was one thing, at mid-twentieth-century, for a fictional character to buttonhole readers with arcane knowledge, but it’s quite another to talk like this today, when we’re all rotten with information, eager to spill our guts. American Genius, A Comedy was timely in 2006, and still feels queasily of our moment.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism is published by New York Review Books. In Pieces, a collection of his essays on art and literature, will be published by Sternberg Press later this year.