Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

The falling of walls: in Catherine Lacey’s fourth novel, an uneasy proximity between performance and reality.

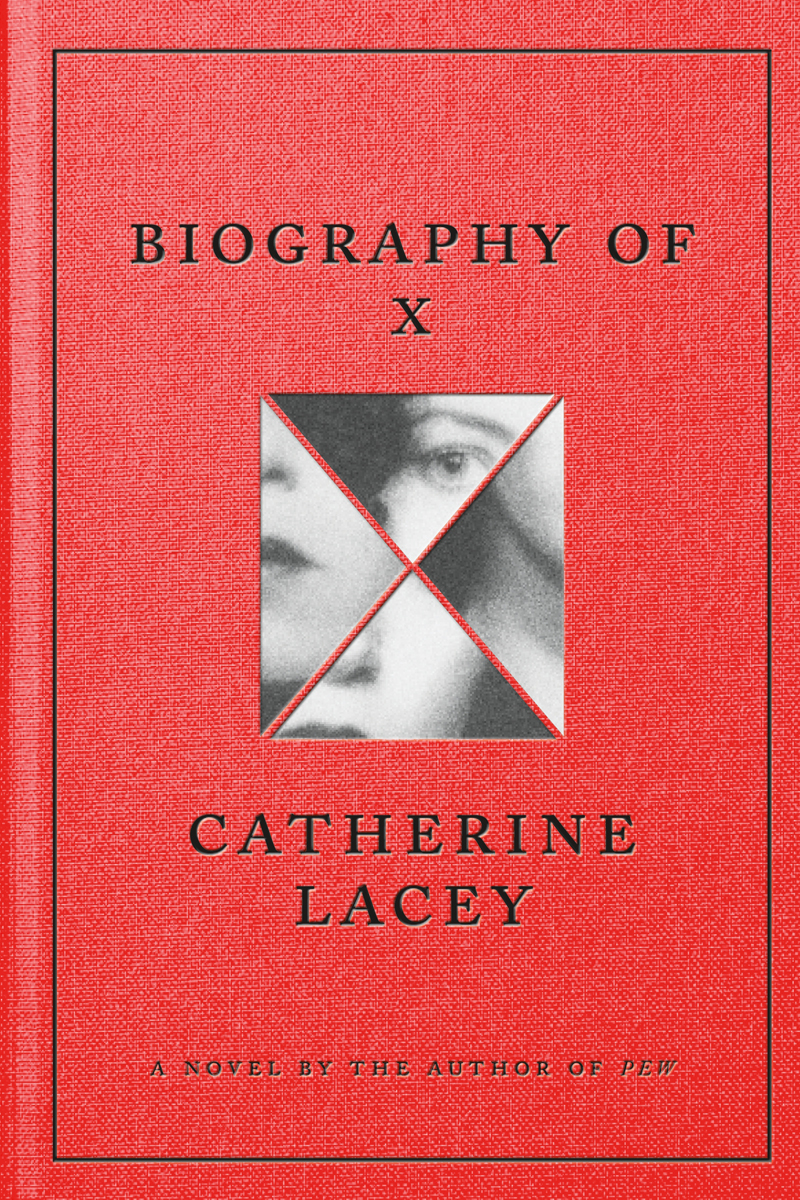

Biography of X, by Catherine Lacey,

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 394 pages, $28

• • •

The narrator of Catherine Lacey’s expansive and devious fourth novel is C. M. Lucca, a former crime writer, and widow of X: an artist, novelist, and musician with mysterious origins and a cruel but compelling demeanor. “From the very start, I knew that X possessed an uncommon brutality, something she used in both defense and vengeance.” After X’s death in 1996, her wife rebuffs the inquiries of Theodore Smith, unsanctioned but tenacious biographer of the deceased art monster. He publishes anyway, and Lucca sets out to write a “corrective biography” of a woman who has remained enigmatic even to her. The result is a species of cultural and political picaresque: a giddy, sometimes grueling journey through real and imaginary histories of America in the last decades of the twentieth century. Biography of X bristles with correspondences and connections to upscale and downtown art and culture, but is also an energetic fantasy about an America that might have been.

Putting together the story of X takes its toll on her grieving partner: “And now I am busy, so busy, day and night, ruining my life.” In fact, X, with her lies and lures, her fits of infidelity, and sudden disappearances, has been doing a number on the hapless narrator all along. And yet she has remained fascinated by, and continued to love, this impossible person. It seems that X arrived in New York in 1972 and worked her reverse-Zelig act for the next quarter century: she’s conspicuously at the heart of every scene, accelerates to her own advantage each cultural or subcultural turn, collaborates with (or else imperiously dismisses) key artists of the era. “She lived in a play without intermission in which she’d cast herself in every role.” Under a succession of noms de guerre—including Dorothy Eagle, Clyde Hill, Cassandra Edwards—she publishes wildly successful novels but hides behind prostheses and sunglasses, makes notorious artworks that demand much of the viewer (but may not actually be any good), records and writes songs with the likes of David Bowie and Tom Waits. Nobody seems to notice that it’s the same person time and again, with a new name and new image.

Around this maddening personality and possible charlatan—she is variously rumored to work for the FBI or as a spy for the Soviet Union—Lacey has assembled a comic array of real people, more or (usually) less themselves. X follows Sophie Calle around for an art project; she lives with the 1950s folk singer Connie Converse (who in real life vanished in 1974); she cracks wise and accusatory at Richard Serra. Her widow’s task, through diaries, letters, and interviews, is to figure out who X was behind the veils of her constant self-invention; but for the reader there’s another question: Who is she in real life? In 1972, X is in New York sporting cropped hair, torn jeans, and combat boots: punk before punk, art-brat twin to Patti Smith. Later, calling herself Věra, she makes increasingly antagonistic but also self-involved and somewhat pompous performance works, so that one cannot help thinking of Marina Abramović. The conceiving of herself as a character, inhabiting that character and then finding herself trapped by it—are we meant to be put in mind of Susan Sontag? (This clinches it, when we think of Sontag’s desire to be known as novelist not essayist: “Acclaimed for the wrong things—her constant and unsolvable complaint.”) Less lofty comparison: the figure of X compiles aspects of JT LeRoy—literary fame, celebrity endorsement, blatant sham that looks unbelievable in retrospect.

Subtending all of this: a stratum of footnoted commentary from real cultural critics whose words have been repurposed or edited to suit the art and personality (or personalities) of X—Lacey supplies a further layer of notes at the end, detailing original wording and provenance. And throughout there are black-and-white photographs, some purporting to be of X. If Biography of X stopped here, at a level of playful reinvention, it would still be a smart and absorbing novel with much to say about art and fame and—actually, art and fame are enough to contend with. But a wider context surrounds the story of X. In 1945, the United States split into three blocs: Northern, Southern, and Western territories. The South became a vicious theocracy, and the North a place with equal marriage laws, where police carry no guns, and the progressive polity owes a debt to Russian-born anarchist Emma Goldman, who was once chief-of-staff to FDR. But just weeks after X died, the territories were reunited—some of her story may be found on the other side of a border wall, now breached.

There are elements of Lacey’s alternate universe—declining birth rates in the South, teenage girls incarcerated and forced into pregnancy—that recall other novelists (in this case, Margaret Atwood). But much of what she imagines is excessive, gratuitous, or oddly beside any satirical point, so that you have to conclude her intentions lie some distance from mere dystopian parallel or warning. Sometimes this happens on a small scale: Connie Converse did not disappear, Frank O’Hara survived his brush with a dune buggy in 1966, Bowie’s mischievous collaborator in his late-1970s Berlin albums was one Brianna Eno. In other cases the alternative is pleasing if implausible: in the Northern Territory in the 1970s, most people call themselves feminists, even if “the definition of ‘feminism’ kept morphing.” Elsewhere, as in the ascendency of Goldman, or a 1943 massacre that kills off prominent male artists so that women may flourish, the detail is so unlikely that it joins the fictions in the life of X as an expression of—what? An idea of American history from the 1940s onward as itself a dream or fantasy?

Something more oblique, I think. At one point Lacey (quoting Merve Emre on Benjamin Moser’s inferior Sontag biography from 2019) points to the naivety of imagining that lives divide easily between private and public, performance and reality. And later, regarding X’s autopsy: “as if we could ever say for certain where she ended and where the world began.” In the end, X is actually a kind of collective, and not at all (at least not quite) a portrait of overweening individuality or egotism. Viewed from the larger historical perspective the novel posits, the American individual also seems shot through with revolutionary as well as totalitarian possibilities.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities: On Art and Fascination is published by New York Review Books. He is working on a book about Kate Bush’s 1985 album Hounds of Love.