Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Berenice Abbott’s classic book, restored.

Documentary in Dispute: The Original Manuscript of Changing New York by Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland, edited by Sarah M. Miller, RIC Books and MIT Press, 311 pages, $34.95

• • •

Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York is a classic of American photography, a register of the city’s shapes and shadows, its energy and enervation, to set alongside other documentary masterpieces of the New Deal era: Walker Evans’s American Photographs, James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor’s American Exodus. Unlike those works, however, Changing New York comes to us radically curtailed: we have never seen it as the artist intended. The book was cofunded by the Federal Art Project (FAP) and the Federal Writers’ Project, and published by Dutton, a commercial house whose editors, removing certain key photographs, found Abbott’s approach both too abstract and too precise. Worse: Changing New York had been conceived as a graphically daring array of image and text—the latter written by Abbott’s life partner, art critic Elizabeth McCausland—but in the published version of 1939, McCausland’s poetic-critical captions had vanished, replaced, as the two women lamented, by “guidebookishness.”

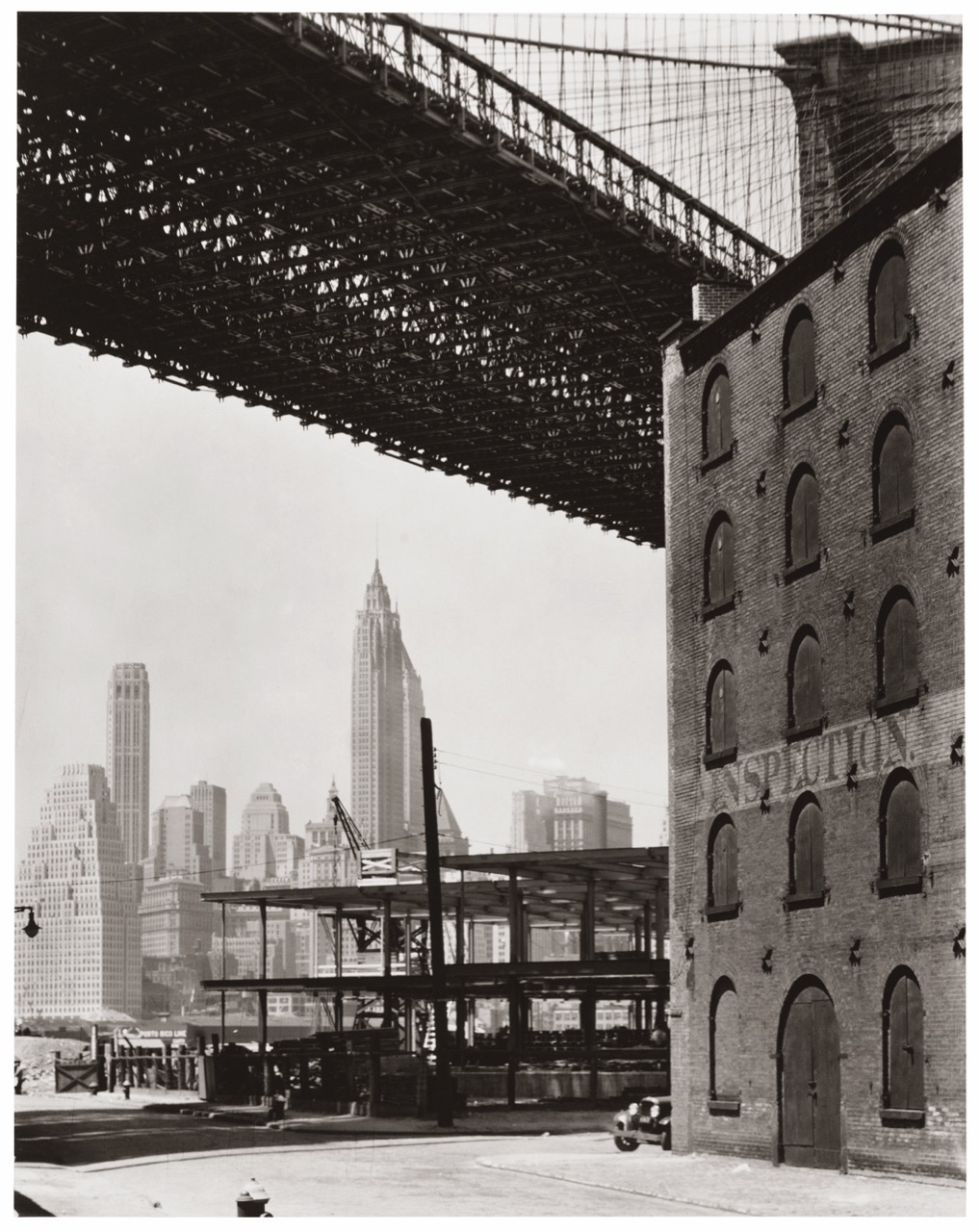

Berenice Abbott for the Federal Art Project, Court of the First Model Tenement in New York City, March 16, 1936. Gelatin silver print, 23.5 × 19.21 cm. Image courtesy Museum of the City of New York.

Edited and introduced by art historian Sarah Miller, Documentary in Dispute: The Original Manuscript of Changing New York by Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland restores the modernist vision of Changing New York to its proper complexity and strangeness, printing McCausland’s commentary alongside the publisher’s, putting back the excised pictures, and adding manuscripts and correspondence that shed light on the work itself and its sorry traduction. Abbott’s photographs are still the brilliantly cold, largely unpeopled heart of the book. There is the “abstract and terrible power” of the skyscrapers; the crumbling geometry of nineteenth-century tenements, bristling with washing lines and poles; the ornate Victorian doorways that might as easily be in London or Dublin; the almost medieval crudeness of teeming storefronts and old streets darkening beneath the cliff faces of new architecture. There are sometimes lone figures outside these buildings, even a few crowd scenes, but fleet-footed street photography was impossible for Abbott. She petitioned the FAP to buy her a small camera (Leica or equivalent) but was turned down. The distanced intensity of her photographs is a product of slow work with a large-format view camera, trained on aspects of the speeding city before they were gone for good.

As Miller puts it, Abbott and McCausland aimed to produce “a type of book and a type of reader-viewer experience that did not yet exist.” McCausland, a self-taught page designer, planned to disrupt the convention of prose description on one page, facing image on the other, and also to upend expectations of the caption as literary form. To accompany Abbott’s initial proposal to the FAP, she wrote a prose poem that gives a sense of her uncommercial tone: “Paradox, behind which stands the substantial frame of things / that were and are and will not be much longer.” McCausland’s captions are sometimes about photography itself, its ambitions and limitations. Elsewhere they marvel at the printed language with which New York speaks to itself; faced with Abbott’s study of a Bleecker Street cheese store, she writes: “The names of cheeses are like a poem for those who love the sound of words—caciotella, latticini, scamorzza . . .” Frequently, she casts the city as a sublime, disquieting geology: “The narrow straightbanked channels of New York streets are like canals cut through granite.”

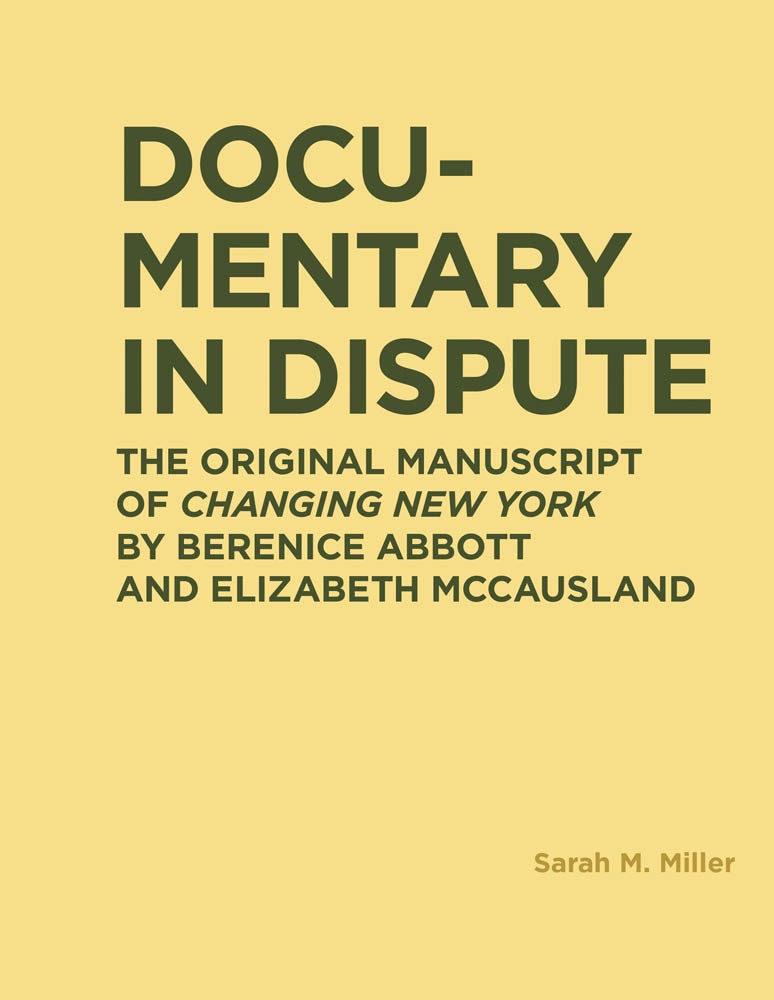

Berenice Abbott, Sailor’s Bethel and Union Square, published in Hound & Horn, April–June 1932; journal tear sheets from Paris Portraits, 1928–35. Scrapbook, 40.5 × 25 cm. Image courtesy Berenice Abbott Archive, Ryerson Image Centre.

Abbott and McCausland thought of their book as a work of “archaeology”—in one of her captions, the critic imagines antiquarians in the thirtieth century examining with curiosity an image of wrought-iron railings in front of nos. 3 and 4, Gramercy Park West. Whence this attitude, with its whiff of Surrealism? A decade earlier, Abbott had returned from Paris intent on publishing the photographs of Eugène Atget, whose entire archive she had bought. There is a lot of Atget in Changing New York: the sense of a decaying city rapidly being razed, the peripatetic photographer’s task to divine its elemental qualities before they disappear. The Surrealists, who had adopted Atget as an elective precursor, are also present in Abbott’s New York: her understanding of documentary is closer to the estranging use of photography in Georges Bataille’s late-1920s magazine Documents than it is to contemporary efforts to capture social reality in post-Depression America. Of course, that is putting it too simply: look closely at Evans and Agee, or slightly later documentary work by the likes of W. Eugene Smith, and you find that photographic “documentary” was apt to align itself at mid-century with avant-garde art and literature.

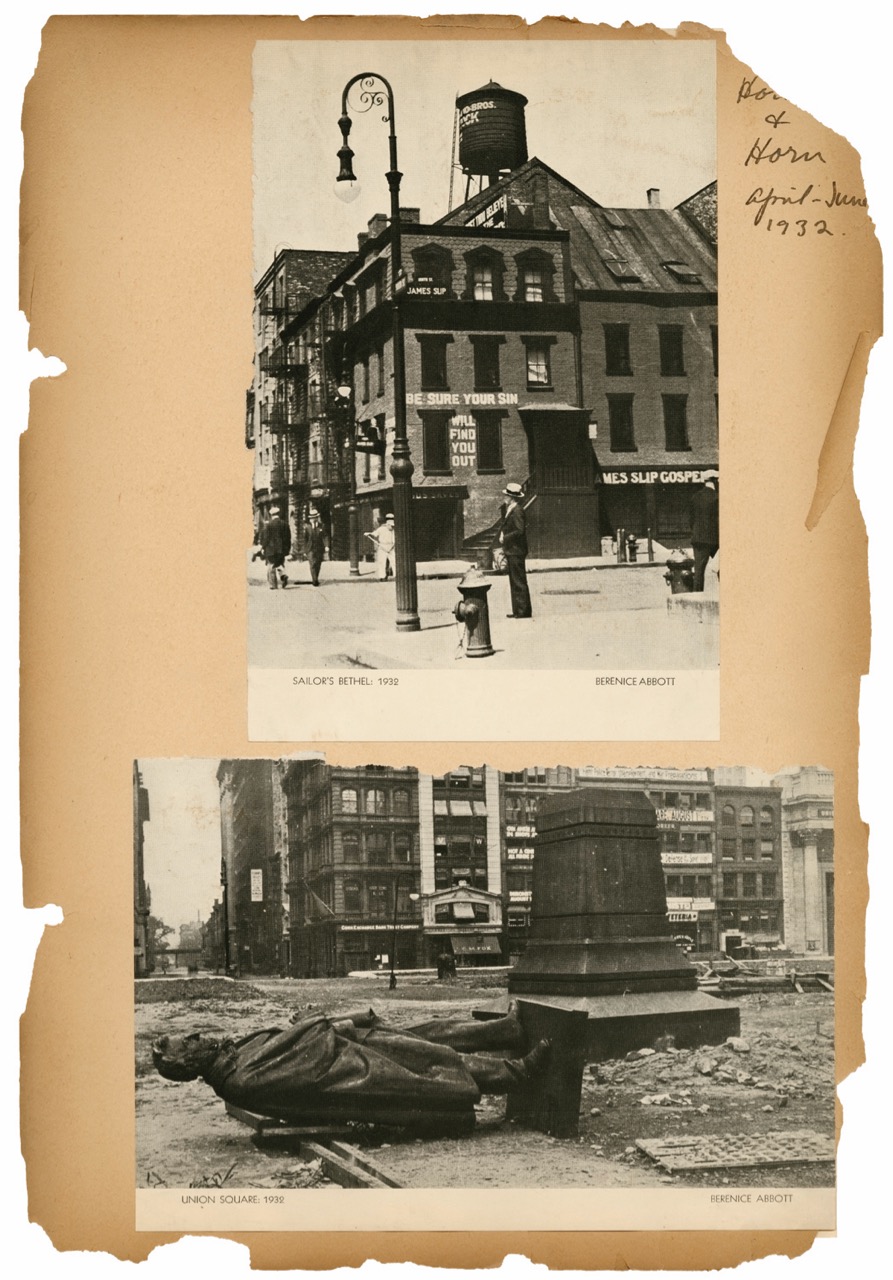

Berenice Abbott for the Federal Art Project, Brooklyn Bridge, Water and New Dock Streets, May 22, 1936. Gelatin silver print, 23.81 × 18.89 cm. Image courtesy Museum of the City of New York.

Dutton stripped much of that entwinement out of Changing New York. Abbott had arranged the photographs alphabetically by title, encouraging accidental juxtapositions. Dutton turned the pattern into a geographically coherent tour of Manhattan, then the boroughs. In the present layout, the first photograph is of the Brooklyn Bridge: McCausland asks us to imagine the straining molecules of steel, their incredible torsion. An editor thought better, and substituted platitudes about the bridge as precursor to New York’s other great river spans. Often McCausland’s more picturesque reflections are replaced with mere statistics: that cheese store, for instance, sells up to 30,000 pounds of cheese each year. The statistics were supplied by a team of anonymous writers at the Index of American Design, and occasionally they hit on a more authentically critical, and modern, tone than McCausland, who can tend to the winsome. A boarded-up building is “a monument of decay”—sure, but some uncredited researcher reveals it is boarded up because the owner will not pay for fire-safety adjustments.

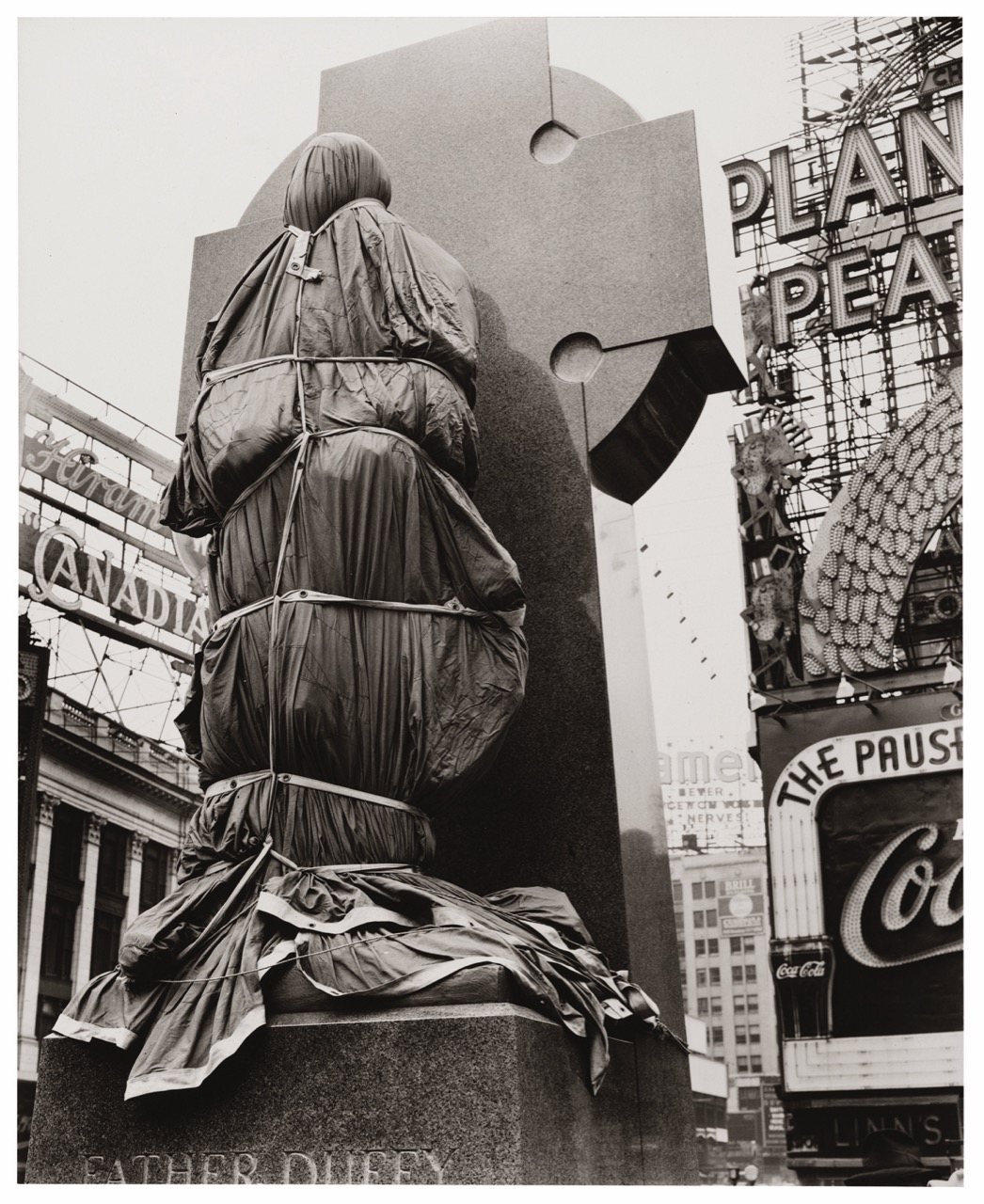

Berenice Abbott for the Federal Art Project, Father Duffy, Times Square, April 14, 1937. Gelatin silver print, 23.50 × 18.29 cm. Image courtesy Museum of the City of New York.

Perhaps the most instructive changes made for the version of 1939 are the deletions, every one of which Abbott and McCausland fought by exasperated correspondence. A Black clergyman on the steps of his Harlem church was removed, and a couple too many storefronts full of handwritten signage; Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center loomed too starkly above a sparse expanse of earth and trees. The publishers, in advance of the 1939 World’s Fair, wanted an aesthetically, racially and socially sanitized city, except where the evidence of race and class might be framed as quaint or colorful: a Black woman and her tiny children on a rundown street in Brooklyn’s “Irishtown.” Abbott, by contrast, saw both the extraordinary surfaces, lines, and angles of a place constantly remade and, with a kind of visionary exactitude, what McCausland called the “extraordinary provincialism of New York.”

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence is published by New York Review Books. His essay collection In Pieces will be published in 2021 by Sternberg Press.