Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

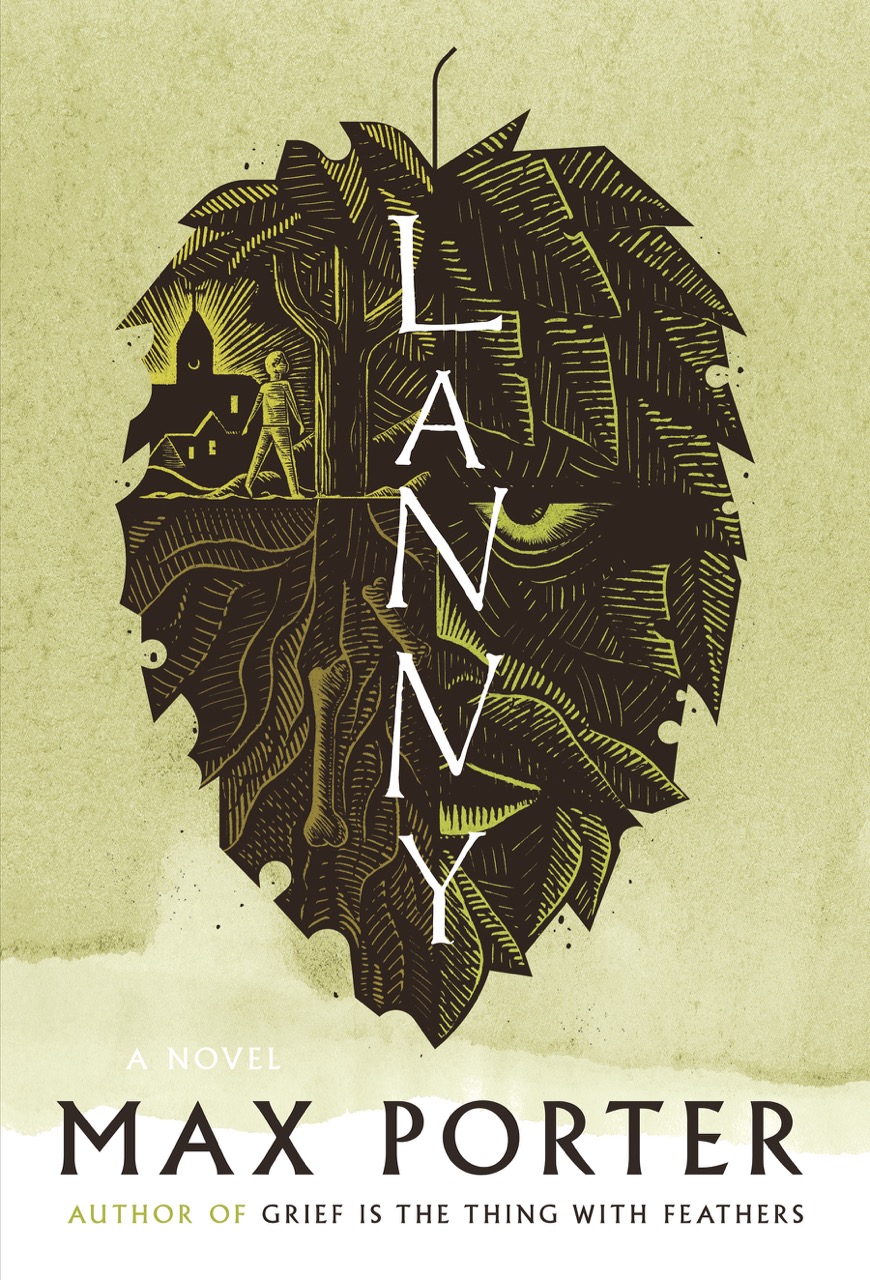

This is England: Max Porter combines the Green Man myth with the trash of modernity.

Lanny, by Max Porter, Graywolf Press, 213 pages, $24

• • •

The English writer Max Porter’s antic new novel is presided over by a monstrous rural personification of chaos, decay, and renewal. Dead Papa Toothwort is a grotesque avatar of the Green Man figure that has roots in pagan religion and the oldest and weirdest of the old weird England. (He—or it—is named for a parasitic woodland plant.) You’ll find the Green Man carved on roof bosses and misericords in medieval cathedrals; Robin Hood is a version of the character, as is the knight in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Many rural festivals across Britain still invoke his embodiment of natural forces, good or ill. At May Day and related spring revels, some villager is frequently tasked with playing the Green Man, and appears tricked up in verdant mask and shaggy vegetation.

Porter is no stranger to eldritch, eloquent nature: his first book, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers (2015), featured a talking crow that visited the narrator and his sons after the death of his wife. In Dead Papa Toothwort, Porter has fashioned a trickster persona made of equal parts Green Man myth and the trash of modernity. He’s a shape-shifting entity who, in the novel’s opening lines, is already many gross elemental things. “Dead Papa Toothwort wakes from his standing nap an acre wide and scrapes off dream dregs of bitumen glistening thick with liquid globs of litter. He lies down to hear hymns of the earth (there are none, so he hums), then he shrinks, cuts himself a mouth with a rusted ring pull and sucks up a wet skin of acid-rich mulch and fruity detritivores.” He lives, if that’s the word, in and around a village in the southeast of England, within commuting distance of London.

The village is ancient, and mentioned in the Domesday Book. But like all such settlements, it’s now home to interlopers from the capital, such as Robert and his wife Jolie, and their mysterious son Lanny. Also to Mad Pete, an older artist, who gives the boy drawing lessons. Lanny is otherwise a loner, bullied by his classmates and distrusted by adults in the village—“creepy little single child,” says one of them. Even Lanny’s parents have begun to suspect his eccentricities, which extend from wandering the village singing and collecting little-boy-style curiosities, to rising in the night to talk to an oak, and hiding under his parents’ bed as they sleep. Freaked by these incidents, Lanny’s mother recalls that when he was a baby he vanished briefly, only to be found nine feet up a tree. Now he’s becoming increasingly interested in stories about Dead Papa Toothwort.

Lanny is divided into three sections—in the second, Lanny abruptly disappears. Jolie, growing slowly distraught, tours the village in search of her son and faces the malign, curtain-twitching side of idyllic English village life: a neighbor complains that Jolie “may as well be a bloody foreigner.” Darkness falls, the police are called, and Pete arrested. He is entirely innocent, but on his release is beaten up anyway by villagers, who spray-paint “Peado” on his walls. As the days pass, journalists flock to the village, and find Lanny’s mother insufficiently sympathetic as a character. Porter is here drawing on a number of infamous British cases of tabloid monstering of innocent parents, neighbors, and older men, and there is a curdled, sickening sense of how easily a community, and then a nation, may turn from shocked empathy to mocking suspicion and spite.

I am not going to tell you a thing about the dead-of-night magic-realist denouement of Lanny, except to say that it is written, like the whole novel, with an extraordinary verve that’s by turns lyric, eerie, and comical. Something of Porter’s textural ambition ought to be evident in the passage I quoted above. Early in the book this earthy style is interspersed with the voices of the villagers, to which Toothwort attends closely. Rivulets of italic conversation literally twist and turn on the page, forming typographic meanders and little orphaned oxbow lakes of text. Graphical experiment aside, this whole strand of the book amounts in itself to a small comic masterpiece, capturing the energy and rue—sometimes the malignity—of contemporary home-counties vernacular. “Sheila’s salted caramel rice pudding sweet Jesus I died and went to heaven / nine English pound, / apple like that, professor says so, quiche au vomit, / the gate worn where she’s leant on it seventy summers, / shrieking like sexed-up foxes, he’s a bum-bandit . . .” Porter’s main characters have discrete and engaging voices, but as the novel progresses these too begin to fracture, until in the final section they turn laconic and telegraphic, white space increasingly filling the page.

But there’s a good deal more going on in Lanny than formal invention and satire of provincial mores. Porter may also have written the first great Brexit novel: a book about the deepest, oldest, strangest sense of itself that England possesses—for Brexit is England’s evil baby, not Britain’s. As the farce attending the UK’s efforts to leave the European Union has dragged on, appeals to archaic ideas of England have grown more strident, more focused on ancestry and land. But look into that deep history, says Porter’s book, and you find not only anarchy—vegetal carnivalesque, the Green Man as lord of misrule—but also a substratum of nature and myth that’s inextricable, like Toothwort himself, from the landfill of modern life and modern language. Lanny is a novel, and Lanny a character, with the most capacious sense of what the land might yield, what community might mean—and what, finally, the spectral, perverse creature that is England might become. “Which do you think is more patient,” little Lanny asks his father, “an idea or a hope?”

Brian Dillon’s Essayism is published by New York Review Books, and his memoir In the Dark Room was recently reissued by Fitzcarraldo Editions. He is writing a book about sentences.