Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

A woman of letters: trying to save the mail in Vigdis Hjorth’s newly translated novel.

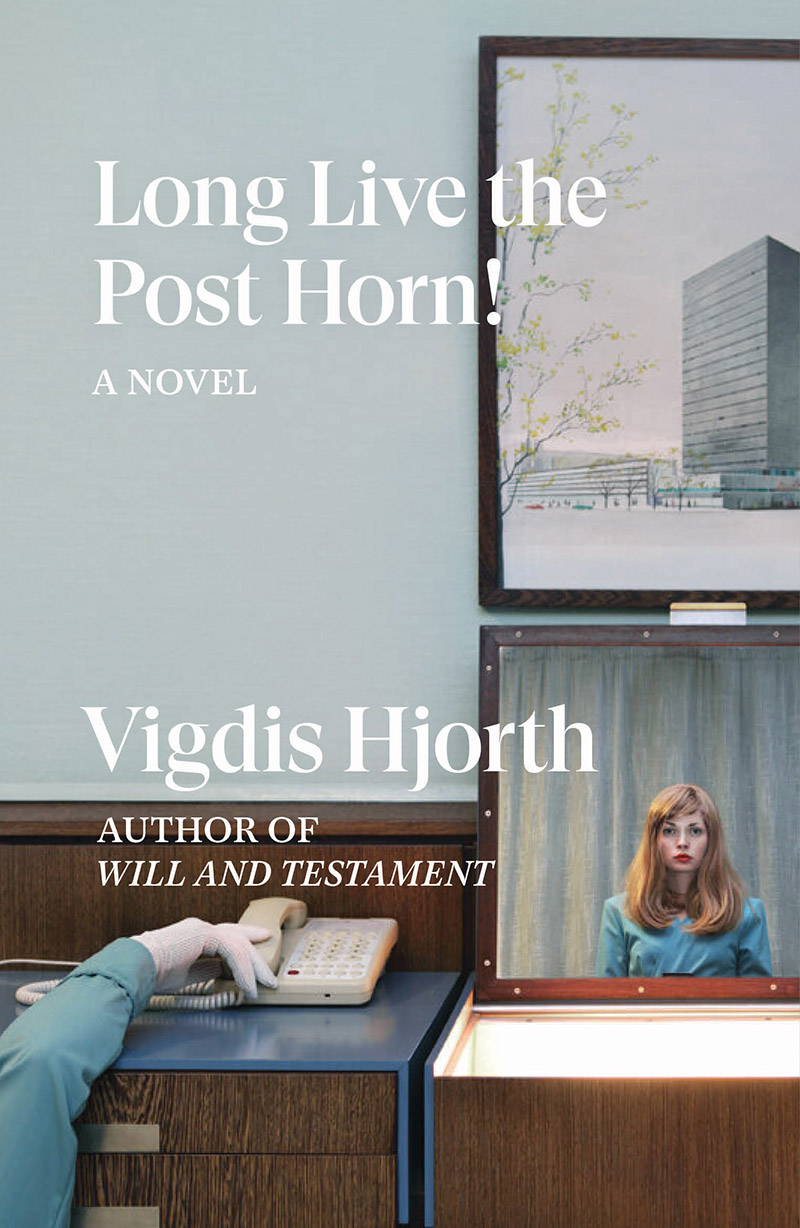

Long Live the Post Horn!, by Vigdis Hjorth, translated by Charlotte Barslund, Verso, 196 pages, $18.95

• • •

Bear with me, because I’m about to describe some decade-old political wrangling about mail delivery in the European Union and environs. In 2008, the EU handed down Directive 2008/6/EC, the bloc’s third statement on the subject of postal services within and among member states. The document, which EU countries were expected to endorse by the end of 2010, required a degree of competition among mail companies, in a field most members had long entrusted to state-owned or partly privatized monopolies. In Norway (an EU affiliate), the government refused to go along with the directive, at least for the moment—a subsequent coalition ratified it in 2013. Not, you might conclude, the most thrilling novelistic material, even in the era of Donald Trump’s effort, by assaulting the United States Postal Service, to stay democracy from its appointed rounds. But in Vigdis Hjorth’s newly translated 2012 novel, Long Live the Post Horn!, the saga of the EU postal directive is an inspired context for a story about personal despair and political awakening.

The novel’s protagonist Ellinor is thirty-five years old and working as a PR consultant. Her current professional commitments: a DIY magazine—the next issue is still full of her typos—and an American restaurant chain called the Real Thing. (Authenticity is a problem for Ellinor: “I had never felt natural.”) The larger project: trying to work out the extent to which she is falling apart. She’s repelled by the people she passes in the Oslo streets: “Where were they going and why, dusty one-bedroom flats in cursory tower blocks filled with junk, crumbling houses between petrol stations and warehouses . . . ” She seems to be allergic to the very air of the city, and cannot tell, when the days start to get longer, if the light is merely in her own head. There seems to be a lid over the world, she thinks, reaching for the most predictable reference point: Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. “I yearned for a breakdown.”

And yet Ellinor is an engaging and funny narrator, ingrained despair the motor of her mordant humor, or at least sarcasm. “Am I lonely, I wondered. Is this diffuse feeling one of loneliness?” She is not sure why her sister has bought their mother an alarm clock: “Why can’t she sleep and sleep until she dies!” Ellinor has a boyfriend of sorts called Stein: a banker in whose life and career she has little or no interest. When introduced to his young son, Truls, she doesn’t even care how old the boy is: “I didn’t know how big children were these days.” The relationship with Stein is a farrago of blackly comic miscommunication; at one point he gifts her a vibrator and brings it to bed with them: “Is that good, he asked for the fifth time and for the fifth time I replied: ‘It’s all right.’ ” The main thing she does not say to Stein: that her PR colleague Dag, disillusioned with the business, has vanished, and she has been left with her remaining associate Rolf to do PR for the postal union—in its campaign against that third EU directive.

The usual media tactics will not inspire the union members: when asked by Ellinor and Rolf to write emotional accounts of their working days, their essential role in their community, and the “social dumping” that the directive will bring, the pair’s efforts are useless. Nobody is paying attention to the website the PR experts have set up to oppose the directive, they can get no traction with the newspapers. Except: one postman, Rudolf Karena Hansen, has written an account of his laboring “to turn dead letters into living ones.” He describes trying to deliver a series of letters addressed to one Helga Brun, but he can find no such person. It transpires she’s a teacher who in 1967, as a young woman, conducted on her pupils a brief and doomed experiment in writing and revelation. Helga Brun believed in the power of the written word, the letter sent (or unsent), the “big words” about hope and labor and love that have fallen out of fashion.

And so Long Live the Post Horn! becomes explicitly a novel about writing, its merits and its perils. The clues had been there from the start of the book: Ellinor’s discovery of an old diary from 2000, her catching Stein trying to conceal a letter (it turns out to be from and to himself) at his apartment, her depressive reveries about what it must be like to stop wanting to scream and start writing instead. By the end of the novel—I won’t steam open the envelope on its denouement for you—Ellinor fully believes in the postal workers and their struggle to save this one small reliable part of daily life and language. She also believes in writing: there are letters from Truls in her mailbox, and she has restarted her diary. Whether we are quite supposed to trust in all this textual redemption is a question that Hjorth leaves wryly unresolved.

Long Live the Post Horn! gets its title from a passage in Søren Kierkegaard’s Repetition (1843) that Hjorth also uses as an epigraph. “Praised be the post horn! It’s my symbol. Just as the ascetics of old placed a skull on their desks for contemplation, so will the post horn on my desk always remind me of the meaning of life.” Kierkegaard’s book is a comic account of despair and melancholia, and a philosophical, or mock-philosophical, reflection on repetition and resentment. (It is also one of the starting points of Existentialism.) Other philosophical controversies seem to hover in Long Live the Post Horn!—the recondite debate, for example, between Lacan and Derrida about whether a letter ever really, truly, reaches its destination. Hjorth invokes all of this lightly, but her novel, despite Ellinor’s tone of sardonic disengagement, is also a treatise, in its way, on the nature of literature and commitment. “Someone had to use the big words.”

Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence is published in September by New York Review Books.