Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

“The photomontage already exists: it’s called the real world”

—a retrospective of the Italian photographer.

Luigi Ghirri, Orbetello, 1974. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri.

Luigi Ghirri: The Map and the Territory, Jeu de Paume, 1 Place de la Concorde, Paris, through June 2, 2019

• • •

The Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri, who was born in 1943 and died at the age of forty-nine, spent a decade working as a surveyor: a meticulous profession that both prepared him for photography and gave him something to escape from. When he quit his day job in 1973, he’d already begun to amass a body of work that is witty and rigorous, as much concerned with the seductions of color and form as it is with critiquing the modern lure of images. The Map and the Territory, at the Jeu de Paume in Paris, is (surprisingly) the first retrospective of Ghirri’s work outside Italy. The show takes its structure from his 1979 exhibition Vera fotografia, where he showed four hundred images in fourteen discrete categories, including Still Life, Kodachrome, and Italia ailati. Borrowing Umberto Eco’s terminology of the time, Ghirri declared each of these groups an “open work” that expanded from the singularity of the image to compose a potentially endless conceptual series.

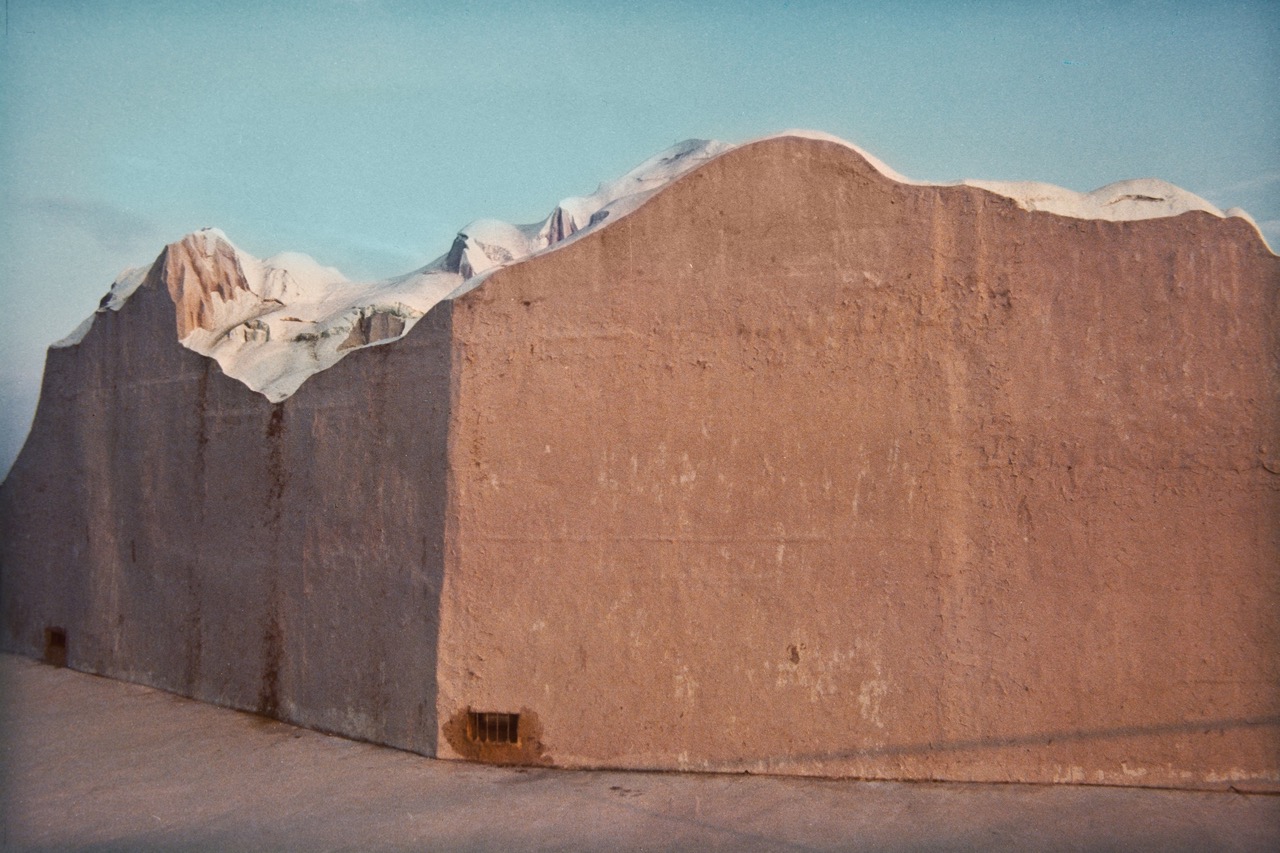

Luigi Ghirri, Engelberg, 1972. Image courtesy CSAC, Università di Parma. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri.

That Ghirri could also do laconic perfection at the level of the single, small color print—this is one of many pleasures in the Jeu de Paume show. Consider the strain of his art that is all about the photograph itself, its ubiquity in daily Italian life in the 1970s. Ghirri wrote: “Reality is being transformed into a colossal photograph, and the photomontage already exists: it’s called the real world.” He photographed many postcards, advertisements, colorful posters decaying on brick walls, and studio photographers’ kitschy portraits in their shop windows. Three older tourists stroll past a billboard advertising Sprite with a thirst-quenching image of waterfalls; snow-capped mountains rise in the background, out of their view. So many of Ghirri’s tightly framed pictures consist of this succinct remarking of one thing on top of another. The joyous thing about Ghirri is that his whole critical, conceptual project is fully present in every picture.

Luigi Ghirri, Rimini, 1977. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri.

Most of his best works are unpopulated, even when they address rituals of daily life and garish, ordinary entertainments. In Rimini, in 1977, he photographed an amusement park’s miniature cities and landscapes: Mont Blanc looming comically over the Piazza del Palio in Siena, and in another image a backlot where the Alps are revealed to be a fragile stage set. Nature, in the new world Ghirri captures—perhaps it has always been this way—is a managed entity: tamed, sculpted, or framed to make suburbs, parks, and commercial precincts. He said that in his early-1970s series Colazione sull’erba, “the mythical image of nature and home takes center stage.” There are blowsy window boxes framed by dull concrete, conifers and cacti standing sentry at suburban front doors, and lurking on a patio three potted palms that in the absence of people start to look oddly sentient and sociable.

Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1973. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri.

When human figures do appear in Ghirri’s photographs, they are often pictured from behind: a man looking at a map of Karlsruhe, a lakeside family in Lucerne. Or they are so distant as merely to add scale in a study of landscape or cityscape, real or fake. Some of them are holding cameras; at the Louvre in 1972, a blurred man in the foreground is photographing his partner and children in front of Whistler’s painting of his mother, producing an inadequate snapshot of family and painting. In a very few cases, Ghirri gets close to his subjects and faces them head on, as in a couple of photographs of tourists squinting in the sunlight of the Piazza San Marco in Venice—but again the pictures seem to be about the limits of vision, the priority of the city as icon over the glaring, noisy reality of the square. Ghirri’s interest in the rituals of vernacular photography also led him, in his Slot Machine series, to rephotograph instructional images from camera manuals, producing an inventory of clichés that include cute blonde children, coy near-nudes, and trees in silhouette.

Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1973. Image courtesy CSAC, Università di Parma. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri.

Ghirri was a kind of blithe conceptualist, essaying such analyses of the ideological import of images with a geniality that is at odds with the vicious ironies many of his contemporaries aimed to find in snapshots, advertising, and television. He owed a good deal to deadpan series and books by Ed Ruscha. And to American photographers such as Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, and the New Topographics artists of the 1970s. In the catalog for The Map and the Territory, curator James Lingwood points out that Ghirri’s photographs of the 1970s were also made at a time of intellectual ferment: among artists in Modena, where Ghirri lived and made a lot of his work, the talk was of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception, Theodor Adorno’s writings on the culture industry, and Eco’s semiotic approach to contemporary media. In his attitudes to private and public space, in his concern with cartography—there’s a whole section of the Jeu de Paume show devoted to close-up photographs of maps—Ghirri shares something with the playfully constrained fiction and essays of Georges Perec.

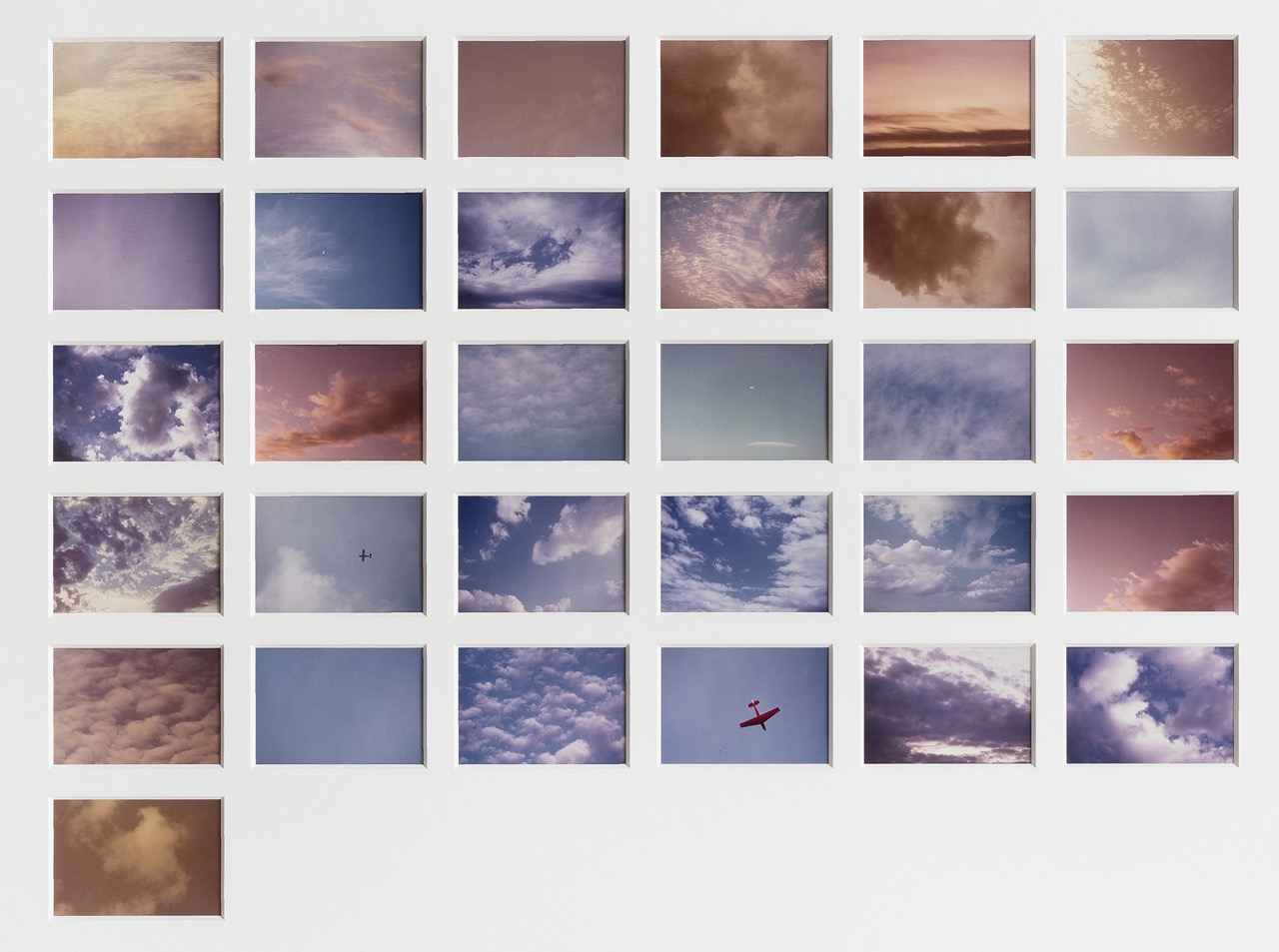

Luigi Ghirri, ‘∞’ Infinito, 1974. © Estate of Luigi Ghirri.

But Ghirri’s is an altogether more visually striking art than such literary and philosophical references allow, and in some ways closer to the work of William Eggleston, who has spoken admiringly of the Italian: “It is the variety of Luigi Ghirri’s work, the eclectic aspect, that most surprises and excites me. I cannot necessarily tell that they are all taken by the same person—which is a compliment!” If Ghirri’s conceptual strategies resemble those of certain of his contemporaries, the images themselves are brighter in aspect and attitude, literally so in a series such as Infinito, from 1974. The photographer pointed his camera at the sky each day for a year; he “wanted to confront the impossibility of translating natural phenomena.” A doomed serial project, and yet here we are: inspecting, in Ghirri’s grids of the resulting snapshots, the balmy typology of clouds, varieties of infinite blue, the mundane miracle of looking.

Brian Dillon’s books include Essayism, In the Dark Room, and Objects in This Mirror. He is working on a book about sentences.