Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Kidnapping, cancer, and Robert Walser: an autobiographical novel by Gabriela Ybarra.

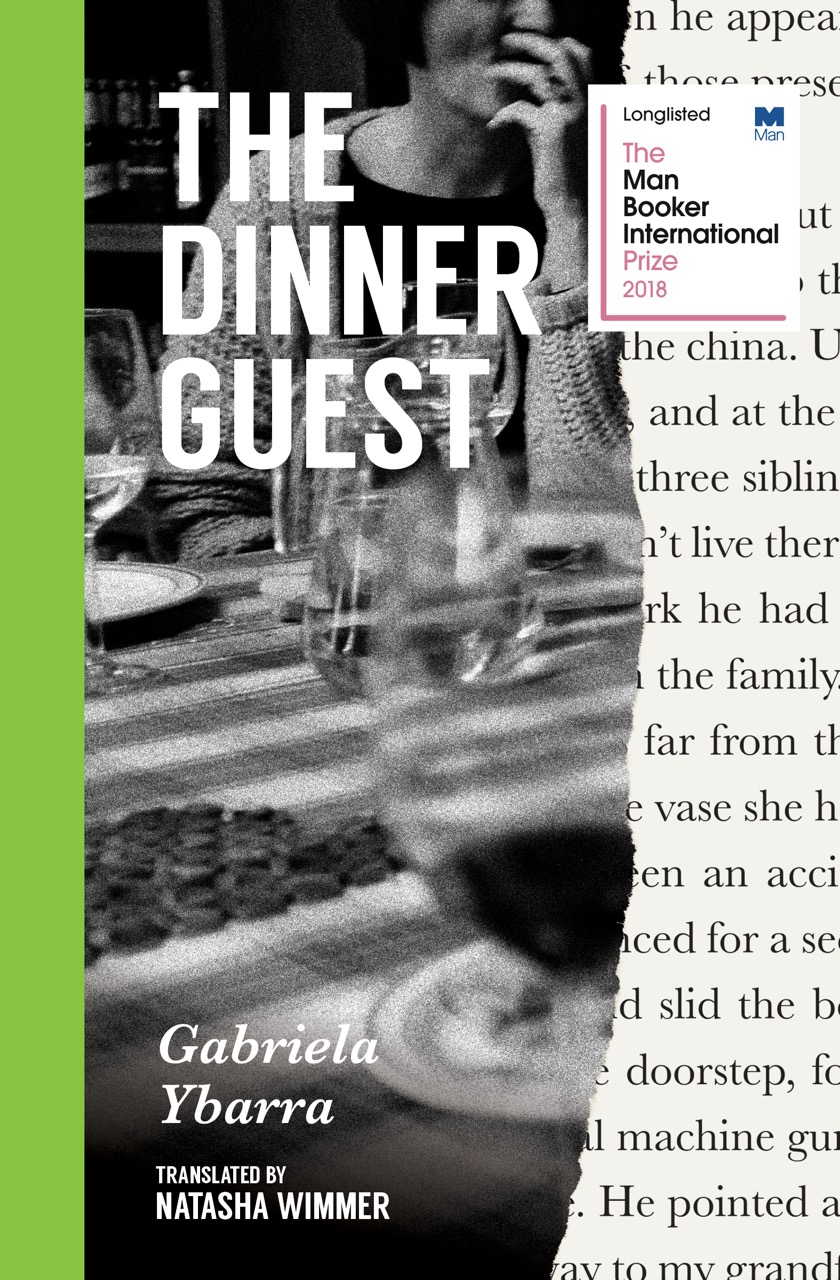

The Dinner Guest, by Gabriela Ybarra, translated by Natasha Wimmer, Transit Books, 144 pages, $15.95

• • •

In the Spanish writer Gabriela Ybarra’s family, they say there should be an extra place set at the table during every meal—for the figure of death, which may snatch them away at any time. “Every so often he appears, casts his shadow over the table and erases one of those present.” The Dinner Guest, which was longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2018, is Ybarra’s first novel, and in part an autobiographical effort to put historical flesh on that specter. It’s in some respects a daringly ambiguous debut, in others a book that doesn’t seem to notice its own lapses or lacunae.

In 1977 her grandfather Javier Ybarra, a nationalist politician who had been mayor of Bilbao, was kidnapped and shot dead by the Basque-separatist terror group ETA. Gabriela Ybarra was born six years later, and as she grew up heard only veiled allusions and rumors regarding these events: a degree of indirection that her book repeats, even as she (or her narrator) tries to counter it. She quotes newspaper clippings, letters sent between the kidnapped man and his family, even crossword clues used to try and get a message to him. Fifty pages in, the oblique history of Javier’s killing gives way abruptly to an account of the death of the author’s mother from cancer, in 2011. Here, in place of media reports and archive material, we read apparently unadorned notes, diary entries, and emails from the six months of her mother’s illness, and its aftermath. But it’s as if 2011 were a lifetime ago, and just as obscured by its documentation as the kidnapping and murder: nothing in The Dinner Guest is quite within a reader’s reach.

This distance feels justified in the opening chapters, when despite the vivid awfulness of the abduction, the details are confused. Did the masked kidnappers, who burst in one May morning, handcuff all of Javier’s children to a brass bed, or leave his young daughter alone? Did Javier dare the terrorists to kill him at once? Or did he say instead, as one of his sons later had it, that “the worst you can do is shoot me”? Was his body dragged from the sea, or discovered in a plastic bag, dumped on a hillside? Why was there grass in the dead man’s stomach? Who was there at his autopsy? The narrator learns no answers to these questions from her family, but instead goes looking on the internet, where she finds news stories and photographs, including one of her grandfather’s body being loaded into a hearse. None of it quite coheres or comes into focus; even when Ybarra has mostly done with it, the story is “mixed with others that my father told me about Pompeii, Degas’s ballerinas, Darío’s ‘The princess is sad’ poem, and Max Ernst’s bird men.”

In the second part of the novel, things are only apparently more immediate. We sit with the narrator in a hospital’s radiation department, where her mother was treated—but it’s a year after her death, and the diaristic notes are being written at some debilitating remove: “I feel the same lethargy I felt a year ago. The same fog in the head. . . . I’ve only been in this room for five minutes and I want to leave.” Instead of yielding to this effort to revisit the past, the narrative emerges in fragments and half-formed anecdotes: her mother traveling to New York (where the narrator has been living) after the first diagnosis, her erratically optimistic urge to buy an apartment in Brooklyn, her physical decline that makes her look at first like a skinny adolescent. And, inevitably, her death, which the narrator is not in the room for—because she thinks her mother, slipping into delirium and unconsciousness, already no longer exists.

This last is an example of something Ybarra is very good at: describing a failure to adequately face the reality of death, which sometimes happens when a young adult loses a parent. A sort of bravura intervenes between the orphan and the event. The narrator’s father has buried the fact of his own father’s violent death, claims it affected him not at all—his daughter, in turn, both keeps her mother’s demise at a distance, and exaggerates its implications: “I didn’t think about death. Or not much. Now I believe that the standard is to die before one’s time.” Such reflections, however, are afforded little space in The Dinner Guest; mostly the book proceeds in a neutrally reporting register: the structure may be fragmentary, but the writing is deliberately flat and muted, tending to the present tense and a simple past, quite untroubled by lyricism, irony, or despair. (Perhaps it is uncharitable also to note, in a book about violent and protracted loss of life, and the struggle to come to terms with such, that Ybarra portrays her family’s obvious privilege as if it were a simple fact of nature.)

There are places in The Dinner Guest where Ybarra seems to aspire to a more self-conscious literary project. On a very few occasions, she gives us on the page the visual evidence she’s discussing in the text: two photographs of her father still handcuffed, a screenshot from her search for pictures of her mother. At such moments, author and narrator seem inseparable and equally at sea amid the evidence, both looking for images or artefacts that will secure the story. What are we to make, though, of Ybarra’s (or is it only her character’s?) retelling of the death of Robert Walser, whose 1917 novella The Walk she has been reading, and her decision to reprint a famous photograph of his corpse lying in the snow? It seems like simple overreach: a book that has kept its own two narratives at such curious distance now invoking a work, and an image, that will supply some missing insight or profundity. The more generous reading is that the awkwardness belongs not to Ybarra, but to a character she knows, and wants us to know, is not telling us all she could or should have.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism is published by New York Review Books, and his memoir In the Dark Room was recently reissued by Fitzcarraldo Editions. He is working on a book about sentences.