Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon

Audrey Schulman’s new novel tells a profound tale of mind control, misogyny, language learning, and interspecies connections at a 1960s marine research facility.

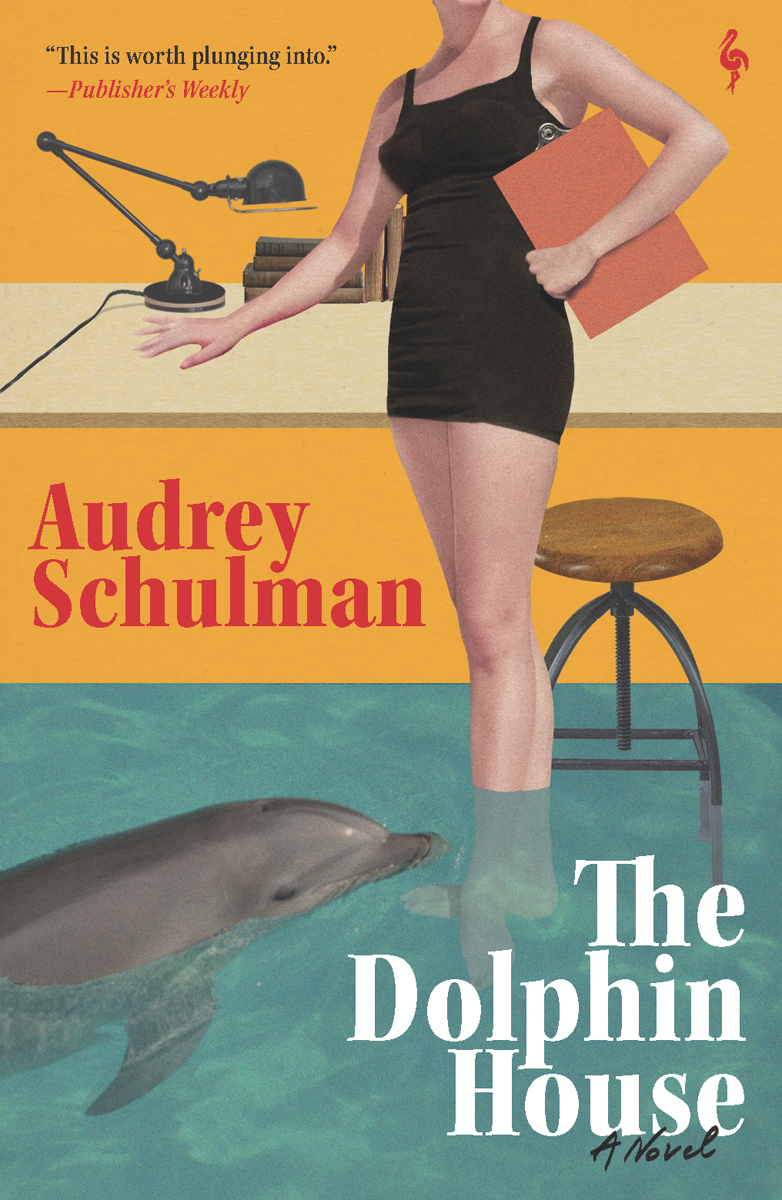

The Dolphin House, by Audrey Schulman,

Europa Editions, 314 pages, $14.99

• • •

“Within the next decade or two the human species will establish communication with another species: nonhuman, alien, possibly extraterrestrial, more probably marine.” These are the opening words of Man and Dolphin, a 1961 book by the American physician, neuroscientist, “psychonaut,” and all-round academic racketeer John C. Lilly. In his book-jacket portrait, Lilly is a suspiciously clean-cut man of mid-century: no surprise to learn he’d been involved in mind-control experiments in the early 1950s. By 1961, his research had led him to study the brains of monkeys and marine mammals; he’d also begun building a research facility on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas to communicate with dolphins. His book later inspired a 1973 movie directed by Mike Nichols, of all people. (Tagline for The Day of the Dolphin: “Unwittingly, he trained a dolphin to kill the president of the United States.”) By that time, Lilly had abandoned cetacean studies for his other enthusiasms: psychedelic drugs and sensory-deprivation tanks.

Audrey Schulman is not the first novelist to draw from Lilly’s absurd and sinister career; The Day of the Dolphin was indebted to Un animal doué de raison, a sort of Flipper-goes-to-war satire from 1967 by the French writer Robert Merle. But Schulman, whose earlier books include Three Weeks in December, The Cage, and Theory of Bastards (all involving animal research or natural history), is less interested in the picturesque character of Lilly—friend of LSD advocate Timothy Leary, suborner of funds from actor Burgess Meredith—than in the intimate and wider implications of his studies. Schulman’s protagonist is not the scientist himself but Cora, a young woman, based on the real-life Margaret Howe Lovatt, who works as his assistant on St. Thomas, and works against his would-be-rational fixations and heartless methods. But The Dolphin House is only partly a novel about scientific overreach: it’s also a tender tale (like a large portion of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein) of language acquisition and love, a detailed account of what it is like to learn about your own body by confronting another (no matter its species), and a salty reminder of postwar American misogyny. These aspects don’t all move with the same sleek agility.

We first meet Cora as a partially deaf waitress at a Florida nightclub, in 1965: dressed in Playboy-style bunny costume, subject to the roaming hands of her boorish clientele. One night, outside the Tampa Theatre, she looks at a poster for South Pacific and decides to move to St. Thomas: “She hoped there, she wouldn’t have to dress like an animal to get a job.” On the island, she wanders into the lab of chief scientist Blum, who, with sidekicks Tibbet and Eh (Cora can’t hear or lip-read his actual name), has been studying the actions and sounds of four dolphins corralled into a lagoon. On land, Cora relies on hearing aids clumsily disguised as eyeglasses, but underwater, she finds that, unlike her new male colleagues, she can hear the dolphins with her whole body: “The noises were vibrating in her bones, she tasted them on her tongue, saw them between her ears. So clear and crisp and three-dimensional.” Though Blum has promoted his research to NASA as preparation for conversing with aliens, Cora is the only member of the team to spacewalk toward the aquatic other, hearing cries from no recognizable mouth or mind.

“If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.” Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous dictum (itself pretty impenetrable) does not trouble Blum or his fellows: in a blatant parallel with Cold War cultural imperialism, the project is apparently to teach dolphins to speak English. Blum’s approach is via the creature’s large brain—capturing the dolphin, cutting open its skull, and inserting electrodes in hope of finding the neural locations for pain and pleasure: “If I can stimulate the pain and pleasure centers, I can motivate them to learn.” Blum has so far got nowhere, but Cora slowly intuits that the dolphins will imitate her voice—speaking via their complicated blowholes—if she spends time with them in their low-gravity universe. Some of the most effective and affecting passages in The Dolphin House describe, as laboriously as a sensitive researcher, the repeated meetings of human and animal. The dolphins at first sound like “A ray gun shooting bursts” or “Marbles dropped one by one into a can.” Later one of them will manage to say “fish,” and perhaps something else. Is it more or less than their prior fabulous sonic repertoire?

I have been ignoring the elephant in the pool. Lilly’s original experiments are best known not for discoveries in animal neurology or linguistics, but for the fact that Lovatt, the original of Cora, is supposed to have “had sex” with a dolphin. In November 1978, over a decade after the St. Thomas experiments ended, Hustler magazine ran a piece titled “Interspecies Sex: Humans and Dolphins”—the accompanying illustration luridly imagined a grinning dolphin in the arms of an ecstatic woman. (The tone of the text, with its heated comments about thirteen-year-old girls, is a deal more troubling than the zoophile subject matter.) In interviews and documentaries since, Lovatt has said she sometimes allowed an adolescent dolphin to rub himself against her, so that afterward they could get on with language classes. Schulman treats the subject in passing, as a detail in keeping with Cora’s farming childhood and practical knowledge of animal husbandry.

The story of the woman who had sex with a dolphin is itself part of the historical ambience of The Dolphin House: the paranoid-prurient style of postwar pop culture’s attitude toward science and pseudoscience, the drift between one and the other. There is not, after all, such a gap between the technocratic fantasies of Lilly the 1960s animal researcher—Blum and Tibbet seem like dual aspects of his character—and the (drugged or therapeutic) altered states of the 1970s. Or between the scientists’ callousness toward the dolphins and their casual or furious misogyny. At times, Schulman’s depiction of the latter starts to sway into Mad Men period cliché: the ashtray, the martini pitcher, the workplace grope. A peculiar note at the end of the novel tells us: “This book is not meant to reflect the way men act now.” Such a caveat weakens Schulman’s grasp on tech hubris and species destruction, themes that make The Dolphin House seem very much of our own moment, and which she treats deftly in her novel’s more embodied, alien passages. Those underwater episodes, liberated from the salacious mythology of her source material, are the most buoyant as well as profound.

Brian Dillon’s Affinities, Suppose a Sentence, and Essayism are published by New York Review Books. He is working on Ambivalence, a book about aesthetic education.