Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Strange geometries, charcoal drawings, portraits, reckless moments: a new MoMA show largely focused on earlier, rarely seen works provides a radical recontextualization of the artist’s flower paintings.

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time, organized by Samantha Friedman with Laura Neufeld and Emily Olek, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West Fifty-Third Street, New York City, through August 12, 2023

• • •

“Best known for her flower paintings” is the phrase that introduces Georgia O’Keeffe in the web copy for To See Takes Time. It’s a kind of caveat—this springtime exhibition, her first Museum of Modern Art retrospective since 1946, includes only a handful of blooms among its more than 120 rarely seen works on paper. In lieu of her famous images, familiar from poster reproductions, it explores the deep cuts: stunning charcoal geometries; stormy, laboriously blended pastels; vivid, bleeding watercolors; and surprising outtakes. Spanning a half century, from 1915 to 1964, they reveal the artist discovering and circling back to her signature biomorphic motifs, using her fantastic effects of extreme magnification and command of sweeping pictorial space in distinctly unflowery ways.

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

More profoundly, the novel groupings in this show illuminate a story of the American Modernist generally overshadowed not only by the popular appeal of her zoomed-in irises and calla lilies, but also the legend of her eccentric glamour, her anomalous status as a woman painter, and her later, bleached-bone Southwestern surrealism. In emphasizing an early, scrappy chapter, before she found success, the exhibition recasts her as a methodical as well as an intuitive searcher, attuned to the work of her avant-garde contemporaries, constantly renegotiating the balance of abstraction and representation in her strange, radical art. While sequential and thematic relationships between O’Keeffe’s individual drawings were not emphasized during her lifetime—in favor, often by her own choice, of displaying finished works as self-contained and discrete—here, nuanced variations on an idea are arranged in dynamic constellations that let viewers into the aloof figure’s process. The experience is almost intimate.

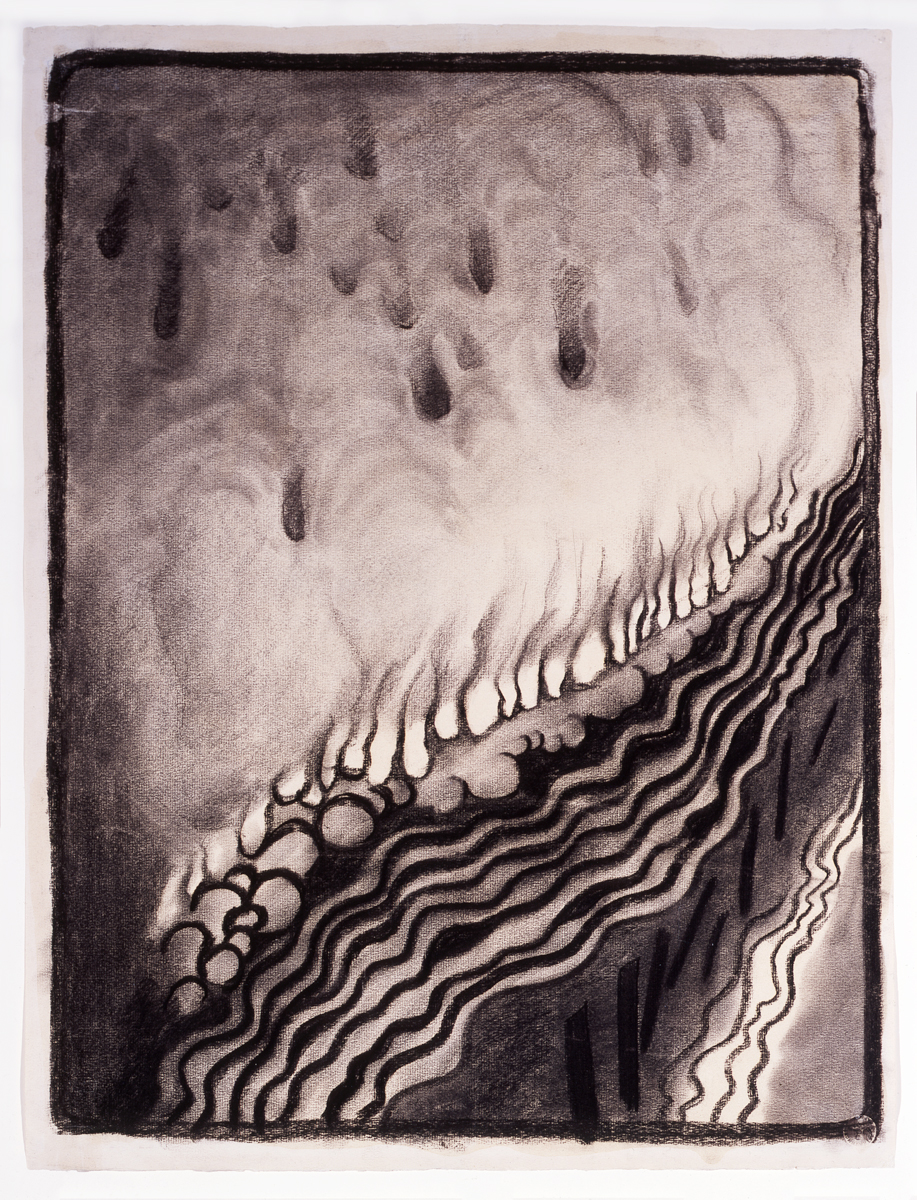

Georgia O’Keeffe, Special No. 9, 1915. Charcoal on paper, 24 3/4 × 19 inches. Courtesy the Menil Collection. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society.

To See begins with O’Keeffe’s consequential decision to render the shapes of an interior world as a counterpart to her practice of outward observation. A feverishly prolific, formative period from 1915 to 1918, when she made more drawings than at any other time in her career, includes a pained nonobjective vision, full of smoky portent, from that first year, titled Special No. 9. (Many of her abstract works on paper were marked “special” on their versos, and this accurate descriptor was eventually incorporated into their names.) The artist referred to the charcoal picture, with its river of black tendrils or flames running diagonally beneath a roiling sky, as “the drawing of a headache.” This quotation, delivered in the wall-label text, continues, describing something of her working conditions back then (when she was in her twenties, teaching art at Columbia College in South Carolina). “It was a very bad headache at the time that I was busy drawing every night, sitting on the floor in front of the closet door.”

Georgia O’Keeffe, Lake George in Woods, 1922. Pastel on paper, 17 × 14 1/4 inches. Courtesy Colby College Museum of Art and the Lunder Collection. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society.

O’Keeffe’s reflections—often taken from her passionate early letters to her friend Anita Pollitzer, and others to gallerist and photographer Alfred Stieglitz, whom she would marry in 1924—are woven throughout the exhibition and accompanying monograph, offering invaluable detail and eloquent insight into specific eras of production and recurring subjects or shapes in her art. The presence of her candid, confiding voice contributes to the sense we’re getting an insider glimpse. Alongside the more philosophical statements (such as the one that titles the show) are notes on practical matters. To Stieglitz, in 1917, O’Keeffe (who was now at another teaching post, in West Texas) wrote of the material used in crisp, saturated works like her Evening Star watercolors, from that year: “Cheap paper like this is a great friend lately—A stack of it almost a foot high makes me feel downright reckless.”

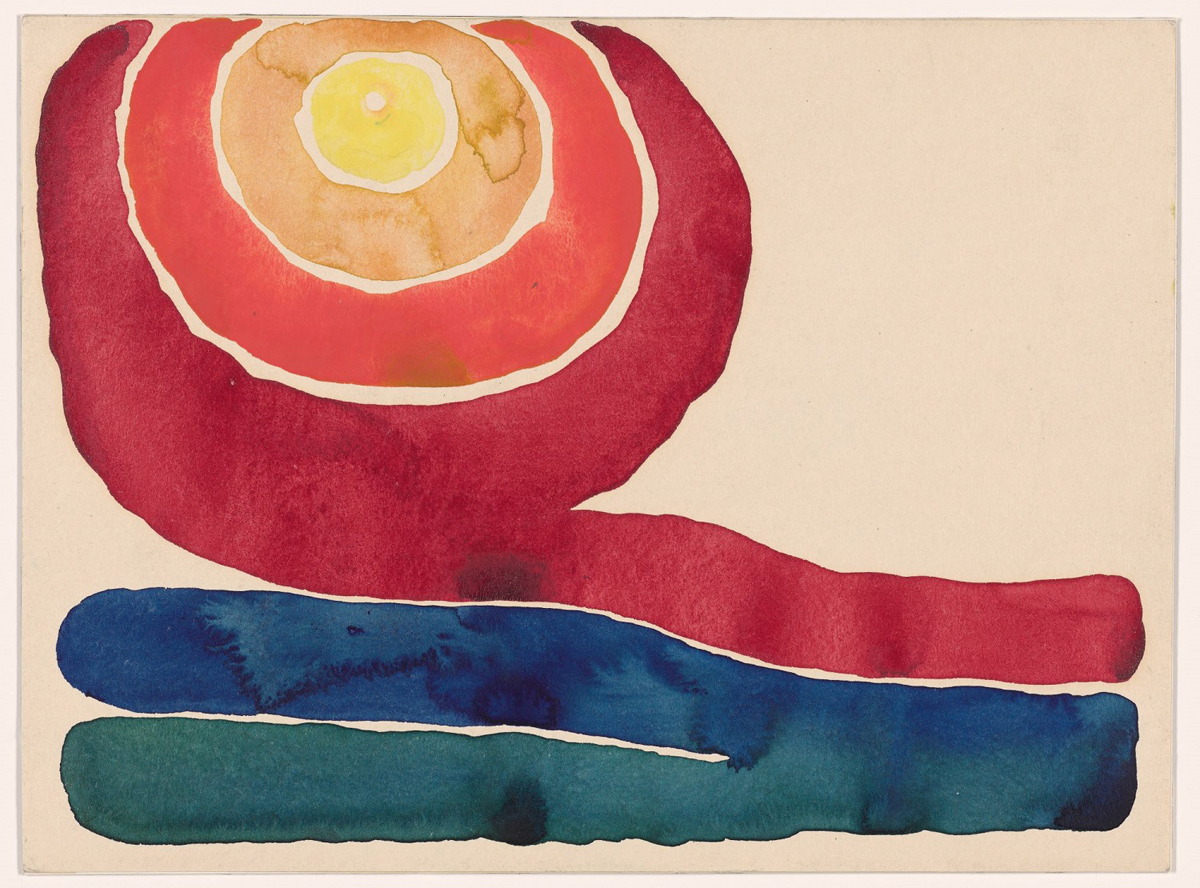

Georgia O’Keeffe, Evening Star No. III, 1917. Watercolor on paper mounted on board, 8 7/8 × 11 7/8 inches. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society.

The series is composed of eight versions of a simplified vista in which a pale-yellow planet hangs over a desert horizon. Dark-rimmed puddles, left to dry on the semi-repellent surface of the cream sheets, lend her fast wet-on-wet colors—orange and red concentric rings in the sky, bands of blue and green below—an aqueous, mottled depth. Mostly, there are only small changes between the iterations, though her final take on the scene, executed on more-absorbent paper, is a hazy outlier, with a cloudy, pinkish, unfurling volume now taking center stage.

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured, center left wall: Evening Star watercolors. Right wall, left to right: First Drawing of the Blue Lines; Black Lines; Blue Lines X.

Sometimes the artist’s groups of related works appear to chart a progressive process of abstraction. Other times, she seems to be considering her options in terms of available materials, as in the three starkly beautiful pictures First Drawing of the Blue Lines, Black Lines, and Blue Lines X, all from 1916. Their shared motif—a vertical mark, like a long laceration, standing beside a zigzagging partner—is rendered in charcoal, black watercolor, and an inky blue, respectively. (This last one was the only watercolor included in her 1946 MoMA show and was given pride of place on the invitation.) In contrast, the Evening Stars don’t seem to follow a logic of distillation or experimentation. They are more like the repetitions of a photographic series—images captured in rapid succession, differentiated by slight adjustments, or by chance mechanical, chemical, or atmospheric events.

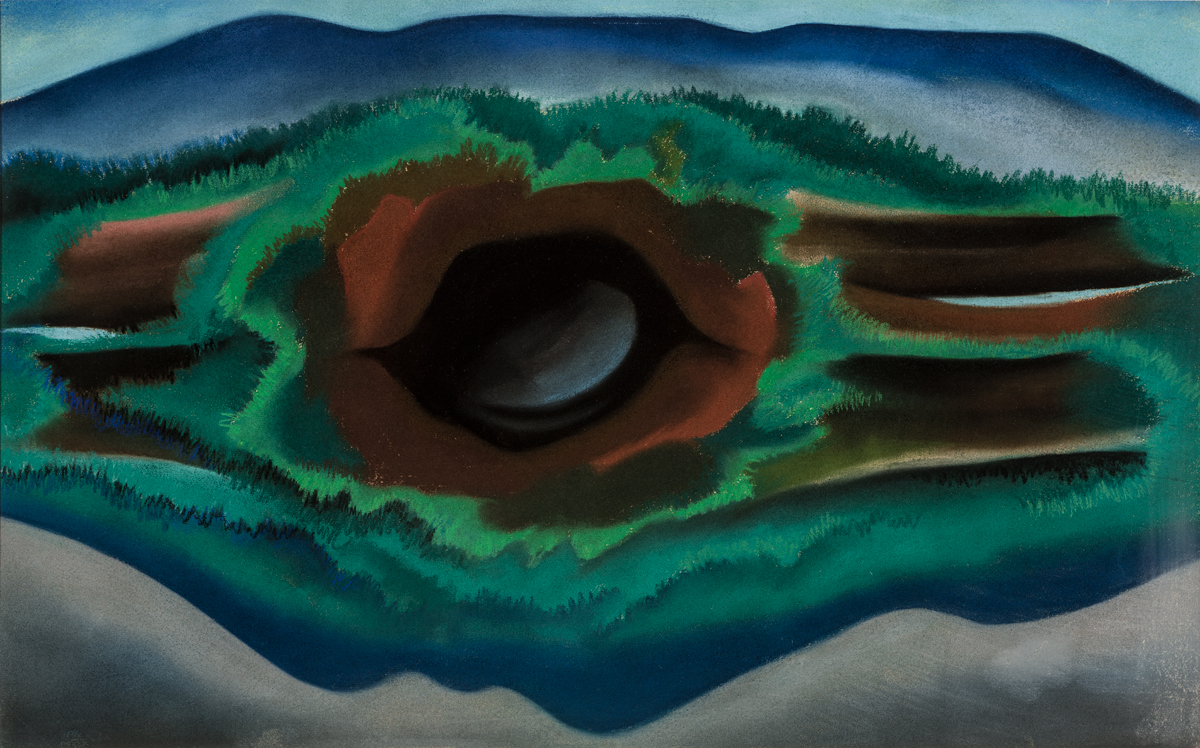

Georgia O’Keeffe, Pool in the Woods, Lake George, 1922. Pastel on paper, 17 × 27 1/2 inches. Courtesy Reynolda House Museum of American Art. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society.

As curator Samantha Friedman points out in her fascinating essay for the accompanying monograph, modern photography, and the painter’s intense involvement with Stieglitz’s practice—as model, onlooker, and interlocutor—was undoubtedly an influence on her sequential production. Two moody, transfixing pastels, Pool in the Woods, Lake George and Lake George in Woods, from 1922 (when O’Keeffe lived, for part of the year, at the Stieglitz estate in New York’s Adirondack Park), share a dark palette and an abstracted subject—a blue-black aperture with a shaggy, striated aura of brown and green. Compositionally, the two images diverge dramatically, as though their common magnetic void was “shot” from contrasting perspectives. The first, horizontal picture resembles an otherworldly landscape, while the latter, with its radial symmetry, seems to show an aerial view. (This bird’s-eye vantage dominates the post-1959 work included in the exhibition, which ends with her airplane-window drawings—stripped-down depictions of earth veined by rivers and tributaries.)

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time, installation view. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Dorado. Pictured: Beauford Delaney portraits, all 1943.

Another expression of the photographic might be found in O’Keeffe’s (rather rare) forays into figuration, such as the 1943 suite of surprising, realist portraits of Harlem Renaissance painter Beauford Delaney—a brilliant portraitist himself. Of the four studiously modeled likenesses, three charcoals show his disembodied face floating on an empty ground. In a luminous small pastel, a bust fills the page. The subtle shifts in light and angle between the drawings demonstrate an interest in the durational aspect of the multipart portrayal. And Friedman notes that the last, color likeness resembles a headshot, deploying the photographic device—used so famously and dramatically elsewhere in O’Keeffe’s oeuvre—of the close-up.

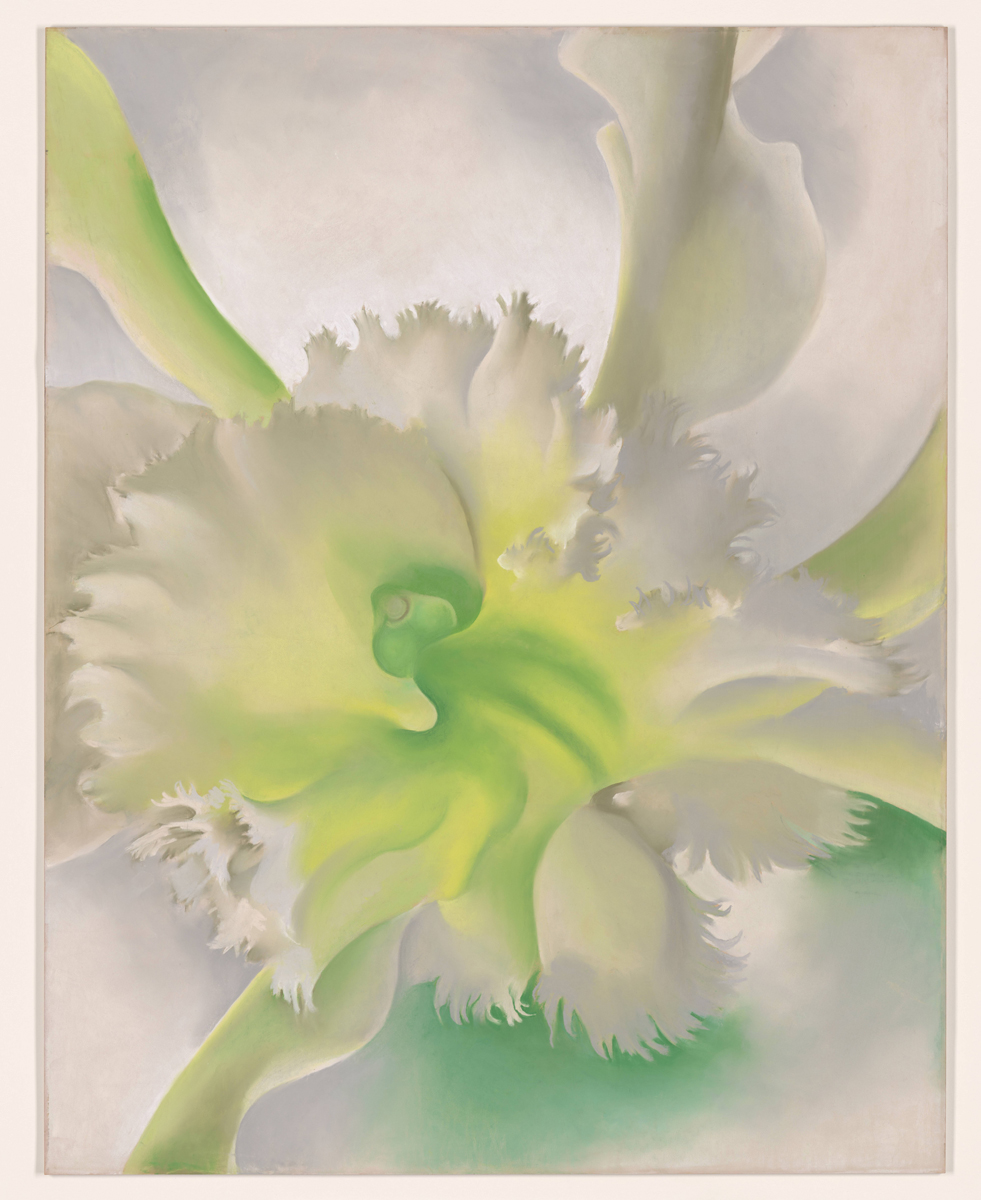

Georgia O’Keeffe, An Orchid, 1941. Pastel on paper mounted on board, 27 5/8 × 21 3/4 inches. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society.

An Orchid (1941) is another realistic but very different kind of pastel close-up, featuring a cropped view looking down at ruffled petals around a blurred vortex, in shades of chlorophyll and snow. It’s an anchoring reference point, an example of the storied, ethereal, enlarged, sexual, seamlessly gradated flowers O’Keeffe is indeed best known for. Such images—which have been variously lauded as a modernist innovation, conscripted into a transhistorical feminist theory of “central core” imagery, and reproduced endlessly as a staple of New Agey normcore decor—have perhaps lost their edge over the years. But, here, contextualized within this essential, wildly contrapuntal show, the alien beauty of An Orchid feels fresh, energized by the mostly non-botanical and small-scale series, which are inspiring in their exacting O’Keeffian discipline, and even better when they are momentarily reckless; when they conjure an image of her as young and unknown, working with a headache, on the floor in front of the closet door.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and musician. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. Her band, Le Tigre, has reunited after seventeen years to tour in 2023.