Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Scrolling the scrolls: a cyber look at the late artist’s large drawings.

Guo Fengyi, installation view. Image courtesy Gladstone Gallery. Photo: David Regen.

Guo Fengyi, Gladstone Gallery, 530 West Twenty-First Street,

New York City

• • •

Editor’s note: As of this writing, Gladstone Gallery is closed to the public due to COVID-19 concerns. The Guo Fengyi exhibition is available to view online via a video presentation and photos on the gallery’s website.

• • •

I didn’t see the Guo Fengyi exhibition at Gladstone: the gallery closed indefinitely the day before the show was slated to open on March 14. And it’s not one I imagined would translate particularly well to an online presentation. It’s composed almost entirely of difficult-to-photograph, ornate works on paper—fourteen vertical scrolls, a couple of them more than twenty feet high, which can only be viewed in full, on a screen, as narrow strips. Given a grid of alluring thumbnails you can, of course, zoom in. Section by section you find the fantastic heads that grow from both ends of the artist’s columns of swirling color, and the other faces that emerge from the spaces in between, like anthropomorphic burls in trunks of enchanted trees. But here, in addition to such images, installation photos and coolly perfunctory videography somehow form a meaningful approximation of a gallery experience—I think.

Guo Fengyi, Tang Dynasty Princess Wencheng, 2004. Colored ink on rice paper, 157 3/4 × 27 1/2 inches. Image courtesy Gladstone Gallery.

I guess it’s impossible to say how well the documentation serves as a surrogate; in truth I judge the success of such quarantine iterations more by how badly they make me want to see the real show. From the images on the website, it seems the Chinese artist’s finely wrought, usually benevolent entities—feathery ink renderings of mythic figures such as Santa Claus, the Statue of Liberty, Princess Wencheng, and the goddess Nüwa—are waiting patiently in purgatory for me, pinned to the dark gray walls of the locked gallery. And though the short video tour, which alternates silent views of the room and tracking shots of individual compositions, has all the charm of drone footage with its smooth scrutiny, its close-ups are far better than what I have haphazardly captured of Guo’s numinous work with my phone in the past.

Guo Fengyi, Nüwa, 2005. Colored ink on Xuan paper, 162 7/8 × 27 5/8 inches. Image courtesy Gladstone Gallery.

She was a remarkable artist, whose profound personal testing of art’s potential feels vital to consider now, in a time of crisis and scaled-back, make-do endeavors. Guo, who died in 2010 at the age of sixty-eight, began to draw when she was forty-seven, after severe arthritis forced her to retire from her job as a chemical analyst in Xi’an (where she lived her entire life). To help relieve the pain, she devoted herself to qigong—ancient techniques of movement, meditation, and breathing—and later began to record her experiences in a journal. Written accounts of her intense engagement with this mind-body practice soon became visual ones. Her initial subjects, sometimes rendered in ballpoint pen, in notebooks and on the backs of calendars, were derived from imagery that appeared to her during meditation. But her work does not necessarily depict visions in a straightforward way: her drawings, often labeled not only with a date, but also with the start and stop time of their creation, are a kind of spiritual artistic process, which she invented in order to heal.

They are also, without question, exhilarating and sometimes divinatory representations of conventionally unseeable realities. Guo’s first US institutional retrospective, which opened in February at the Drawing Center (and will hopefully remain installed there past its scheduled May 10 closing date), boasts fascinating examples of her early, generally smaller works, including diagrammatic imaginings of the human nervous system and the meridians of traditional Chinese medicine; detailed interpretations of Buddhist, Daoist, and Christian icons and cosmology; and depictions of distant places—archaeological sites, the Bermuda Triangle, Egyptian pyramids—as observed on her out-of-body journeys. The survey (and its beautiful accompanying publication that can be read for free online) is an invaluable introduction to Guo’s singular outlook and defining concerns, and it sets the stage for her towering knockouts at Gladstone.

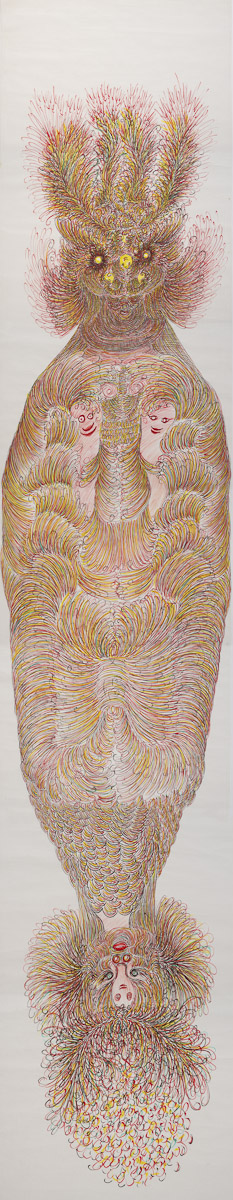

Guo Fengyi, Yamantaka, 2005. Colored ink on rice paper, 278 × 37 7/8 inches. Image courtesy Gladstone Gallery.

Guo sat at a rather small table to make these large pieces, which is hard to believe, and yet obvious once you think about it. Built from consecutive passages of rhythmic calligraphic marks, each of the supernatural figures has a meandering structure and a vibrating radiance. Yamantaka (2005), named for the wrathful Tibetan deity, is an outlier for its fearsome aspects—the monstrous figure’s upside-down, bottommost head grimaces with a fanged underbite—but otherwise it’s typical of Guo’s approach. The sunset-hued strokes that form the volumes of Yamantaka’s many faces and long body read alternately as hair, fire, and pure energy; the scroll’s off-kilter composition, which would have been visible to her only in tabletop-sized pieces as she worked, embodies that thrilling moment, I imagine, when the triumphant sum of her fragmented focus was first revealed.

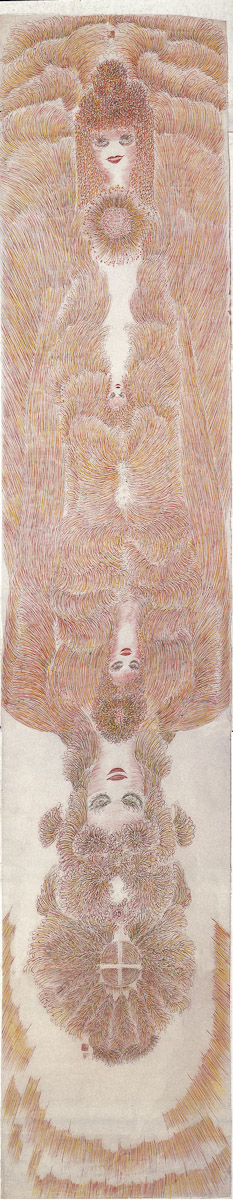

Guo Fengyi, Statue of Liberty, 2003. Colored ink on rice paper, 198 7/8 × 38 1/4 inches. Image courtesy Gladstone Gallery.

In Statue of Liberty (2003), four beatific smiles beam from lovely visages, exuding a cosmic joy that ruffles out in undulating waves. At first, the scroll looks to be rotated 180 degrees—an expansive downward-pointing headdress occupies the scroll’s lower fifth, seeming to denote that the head that wears it is the being’s most important one. Perhaps its incandescent power is propulsive, needed to lift the figure off the ground, though? I trust Guo has a good reason Lady Liberty is not flipped the other way.

While these pictures were realized without a plan, and no recognizable pictorial logic or discernible rules apply, her unique process and superbly confounding results are not random. Footage of Guo’s astonishingly rapid, fluid brush strokes (included in the Drawing Center’s introductory video) show how, as an example of mindful movement, the graceful gestures align with the energetic aims of qigong; and how her confident spontaneity is born not of certainty but of searching. The artist, who often approached a blank page (or length of rice paper) with just a word, theme, or name in mind, once said, “I know my subject only after completing the drawing . . . I particularly excel at subjects I know very little of.” Self-taught and outsider are terms that buzz around her radically eccentric and unabashedly therapeutic art. Depending upon the spirit in which they’re deployed, I think that such descriptors can be fair. But, in Guo’s self-conscious metabolizing of traditional cultural subjects and styles into something wild and new, her work belongs in conversation with insider contemporary artists, too.

Guo Fengyi, installation view. Image courtesy Gladstone Gallery. Photo: David Regen.

There’s a note of bereavement and anxiety in reviews written by soldiering-on critics who grapple with the unavoidable pivot to exhibitions hastily moved or strangely enhanced online, but in Guo’s inimitable work it’s luckily easy to find some inspiration as well. As much as I’d like to see them in person, I don’t mind scrolling down her scrolls on a screen; I love the way they look in the installation shots, their ghostly reflections in the polished concrete floors. More than that, her understanding of art, as a fundamentally spiritual, healing pursuit, is a comfort to contemplate—and her method for making monumental drawings at small tables is something my own ad-hoc homeschool might just try.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.