Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

The art of calamity: a new show of work by the abstract painter.

Julie Mehretu: about the space of half an hour, installation view. Pictured: about the space of half an hour (R. 8:1) series. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Julie Mehretu: about the space of half an hour, Marian Goodman Gallery, 24 West Fifty-Seventh Street, New York City, through December 23, 2020

• • •

There’s a pause following the breaking of the seventh seal, a “silence in heaven about the space of half an hour” (Revelation 8:1) before the seven angels are given the trumpets with which they’ll cue new phases of the apocalypse. It’s fitting for Julie Mehretu to invoke such dreadful suspense right now—the weird, roughly thirty-minute wait—with her expansive new show at Marian Goodman Gallery. Starring a vertiginous suite of paintings completed during lockdown, the exhibition opened on the election’s eve, as coronavirus infection rates spiked around the world. And it’s also fitting, in a way more particular to her, that she takes as her exhibition title the curiously specific duration of the divine intermission—a measure of time described (in the King James Bible) as a space.

In ever-evolving ways, Mehretu has sought to collapse time and space within the bounds of her layered paintings (as well as her drawings and prints) to imagine partial, abstract, nonlinear histories, usually through the lens—by using the records and traces—of calamity. The palimpsest is a defining symbol, or an artistic model, for her. Like the scrubbed and overwritten manuscript page haunted by its previous text, her compositions are built on fraught substrates, attended by ghosts from the start.

Julie Mehretu: about the space of half an hour, installation view. Pictured: Julie Mehretu, Conversion (S.M. del Popolo / after C.), 2019–20. Ink and acrylic on canvas, 96 × 120 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

The Ethiopian-born, New York artist’s work has, for over two decades, variously incorporated architectural drawings, maps, and blown-up, blurred, black-and-white, or lately color, news-media photographs. Sometimes sharp, Suprematist shapes—bright, kitelike forms after Malevich—float above or duck under diagrammatic detailing, pierced by curved lines that recall Kandinsky, or by straight ones racing into a horizonless yonder. Loose vortices and swarms of repetitive marks suggest migratory routes, mass displacement, armies clashing, meteor trails, panicking schools of fish, and explosions. In her dramatic panoramas—she’s known for epic, mural-scale paintings—emergencies of the present day crossfade into cataclysmic events that predate the Anthropocene. (In addition to the Goodman show, Mehretu is the subject of a mid-career survey that’s currently at the High Museum in Atlanta, and scheduled to open at the Whitney in March.)

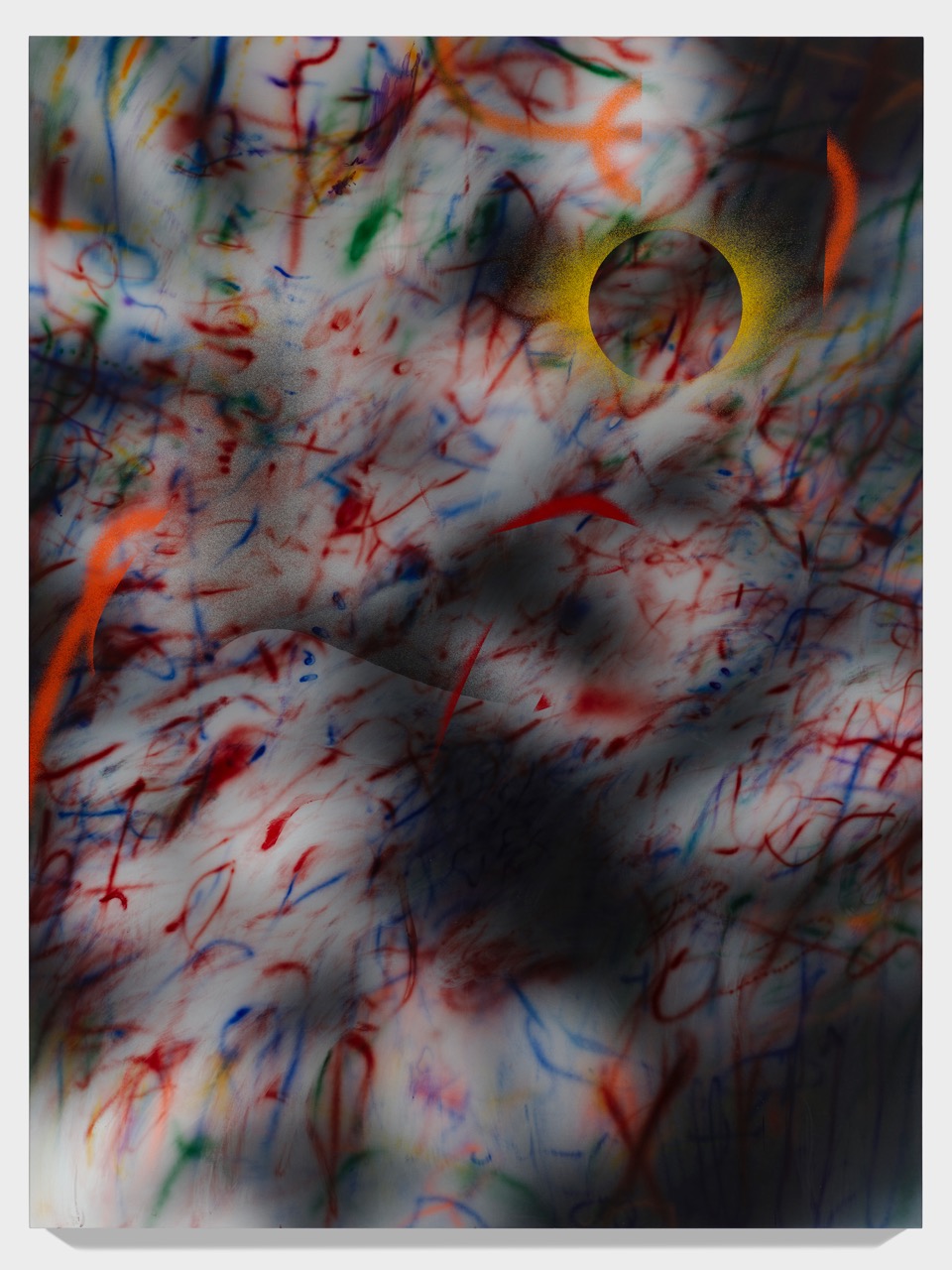

Julie Mehretu, about the space of half an hour (R. 8:1) 7, 2019–20. Ink and acrylic on canvas, 96 × 72 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

The seven most recent paintings on view at Goodman (the aforementioned suite) fill its north gallery; they share the biblical title about the space of half an hour (R. 8:1) (2019–20) and are all eight by six feet—big, but for Mehretu, not especially so. Screen printed, airbrushed, and sanded, as well as hand drawn and painted in ink and acrylic, the pieces have a mood in keeping with the theme of pre-apocalyptic calm—a sense of inexorable drift rather than cyclonic motion suffuses the fiery compositions; their conflagrations are cooled by shadows and black holes. But though the canvases are united by this vague, voluptuous deep-space ambience, one stands apart with its strange, eclipsed sun. In this outlier, it appears that among the artist’s final steps was a fast spray of hazard-tape yellow over a circular stencil in the painting’s upper-right quadrant. Maybe the resulting smoky ball of negative space, ringed with garish light, presages the fifth angel’s imminent darkening of the sky? Regardless, it seems to indicate, almost comfortingly, that the vaporous, flame-streaked abstraction it inhabits is in fact a thrilling landscape. There’s nothing else to moor us here; without the small sun, the works would abandon us in awestruck limbo completely: in quarantine, in 2020, between the past and prophesy—just as their title suggests.

Julie Mehretu: about the space of half an hour, installation view. Pictured, left to right: Julie Mehretu, Black Monolith, for Okwui Enwezor (Charlottesville), 2017–20; Slouching Towards Bethlehem: Third Seal (R 6:5), 2020; Slouching Towards Bethlehem: Second Seal (R 6:3), 2020. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

I can’t help but search for recognizable things, anchors of some kind, when contemplating Mehretu’s wealth of pictures here. (There are three galleries, plus the conference room, full of paintings on the main floor; one more canvas—an elegiac knockout dedicated to her late friend, the curator and writer Okwui Enwezor—accompanies a series of captivating photogravure-and-aquatint prints in the third-floor space.) Perhaps I scan her work more closely, in part, because I know that, for each piece, the artist began with a photographic image, however edited, effaced, and fuzzed out it now is. We’re given (by the press release) the general subject matter of her source material as clues—hurricanes, wildfires, migration crises, the global ascendence of fascism—and, often, more specific references can be found in titles, narrowing somewhat the range of plausible responses to her lush Rorschach tests.

Julie Mehretu, Rise (Charlottesville), 2018–19. Ink and acrylic on canvas, 96 × 72 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Rise (Charlottesville) (2018–19) draws from the shocking—or once-shocking—“Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which infamously coalesced hate groups and militias in reaction to calls for the removal of a statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee in 2017. The underlying photo is indistinct but present in the painting’s out-of-focus depths: a soft-edged patchy shadow, or cluster of dark bruises, encroaches on a chaotic field confettied with red and blue marks, like slashes and floating threads. Sallow hotspots in the scene might be formed by the mob’s grimly ridiculous tiki torches, their lurid halos bleeding together—just a guess, though.

Julie Mehretu, A Mercy (after T. Morrison), 2019–20. Ink and acrylic on canvas, 96 × 120 inches. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Mehretu, in her voice-over for the video walk-through of the exhibition, speaks of this harrowing Trump-era episode as a “reiteration” of the past, and she pointedly pairs Rise with A Mercy (after T. Morrison) (2019–20). This larger, ten-foot-wide, horizontal canvas is named for the great, recently deceased author’s 2008 novel, which also takes place in Virginia—in colonial times, during the first century of American slavery. The composition recalls, with its sweeping scale and windy, roiling drama, Géricault’s famous shipwreck scene, The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19); and, with its rich palette of amber and ash, the blazing-sunset horror of J. M. W. Turner’s Slave Ship (1840), whose original, descriptive title included, as a parenthetical, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On. Mehretu has cited both paintings as influences.

Julie Mehretu: about the space of half an hour, installation view. Pictured, left to right: Julie Mehretu, Orient (after D. Cherry, post Irma and summer), 2017–20; Maahes (Mihos) torch, 2018–19. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Almost wholly abstract, her new work evokes the eerie magic of double exposures—in-camera accidents capturing apparitions—further overlaid with a time traveler’s half-erased, encoded notes. Her laborious process blurs juxtapositions both within and between works to create an effect—or in order to illustrate the truth—of apocalyptic continuity. But fortunately for those who love a silver lining, in Mehretu’s practice, the palimpsest is not an image of despair. To build with layered wreckage one need not replicate the flawed structure visible beneath, it seems to show. And in a silence about the space of half an hour, so to speak, when no one knows what will happen next, she leaves us unsettled but not without possibility, with room for hope alongside ample dread.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum. She is a 2019 Creative Capital awardee and currently at work on a novel.