Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Pointed portraiture and royal symbology tell a revealing story about the Renaissance family’s rule.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, curated by Elizabeth Cleland and Adam Eaker, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York City, through January 8, 2023

• • •

Centuries-old artifacts and the mesmerizing poker faces of royal portraits cast a spell in the dimmed galleries of The Tudors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, one that can’t be broken—not entirely—by the computerized text-to-speech announcement, delivered in a politely sinister male voice, “You’re standing too close to the art, please step back.” Triggered almost constantly by eager visitors peering into vitrines and crowding around paintings on the exhibition’s opening day, the refrain served as a reminder of the insatiable public interest in the fabled royal family.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Henry VIII, ca. 1537. Oil on wood, 11 × 7 7/8 inches. © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

The House of Tudor has lent itself to endless novelistic and cinematic treatments. With a weak claim to the crown and a dangerous shortage of male heirs, the embattled monarchs were constant authors—and targets—of brash and intricate plots to seize or maintain power. And a grand narrative arc is easily pieced from the events of their collective one-hundred-eighteen-year rule, from its breathtaking, bloody start, in 1485, with Henry VII’s underdog victory at the Battle of Bosworth, to Henry VIII’s tyrannical caprice—and of course his six wives—to his daughter Elizabeth’s relatively stable reign, more than four decades long. A sense of resolution, even poetic justice, might be found in the ascension of the never-married “Virgin Queen.” Elizabeth I, the last Tudor to occupy the throne, was born to Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s second wife (a perennial fan-favorite), famously accused of treason and adultery, beheaded when Elizabeth was two.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Here, though, in the long-awaited, first-ever US survey of the cosmopolitan Tudor court’s artist patronage (slated for 2020 but postponed due to the pandemic), where over one hundred objects from the museum’s collection and a host of international institutions and private collectors have been assembled, viewers must read between the lines of the wall text for salacious or morbid particulars. This is not to say the experience is dry: in place of psychological speculation or character development, The Tudors presents a vivid view of the Renaissance dynasty—its tumultuous rule and relationships with Europe during the Protestant Reformation—through its sumptuous interiors, mostly. Tapestries, needlepoint, manuscripts, armor, and paintings offer dramatic, often dovetailing, lessons in splendor-as-statecraft and the legitimizing force of iconographic ornament.

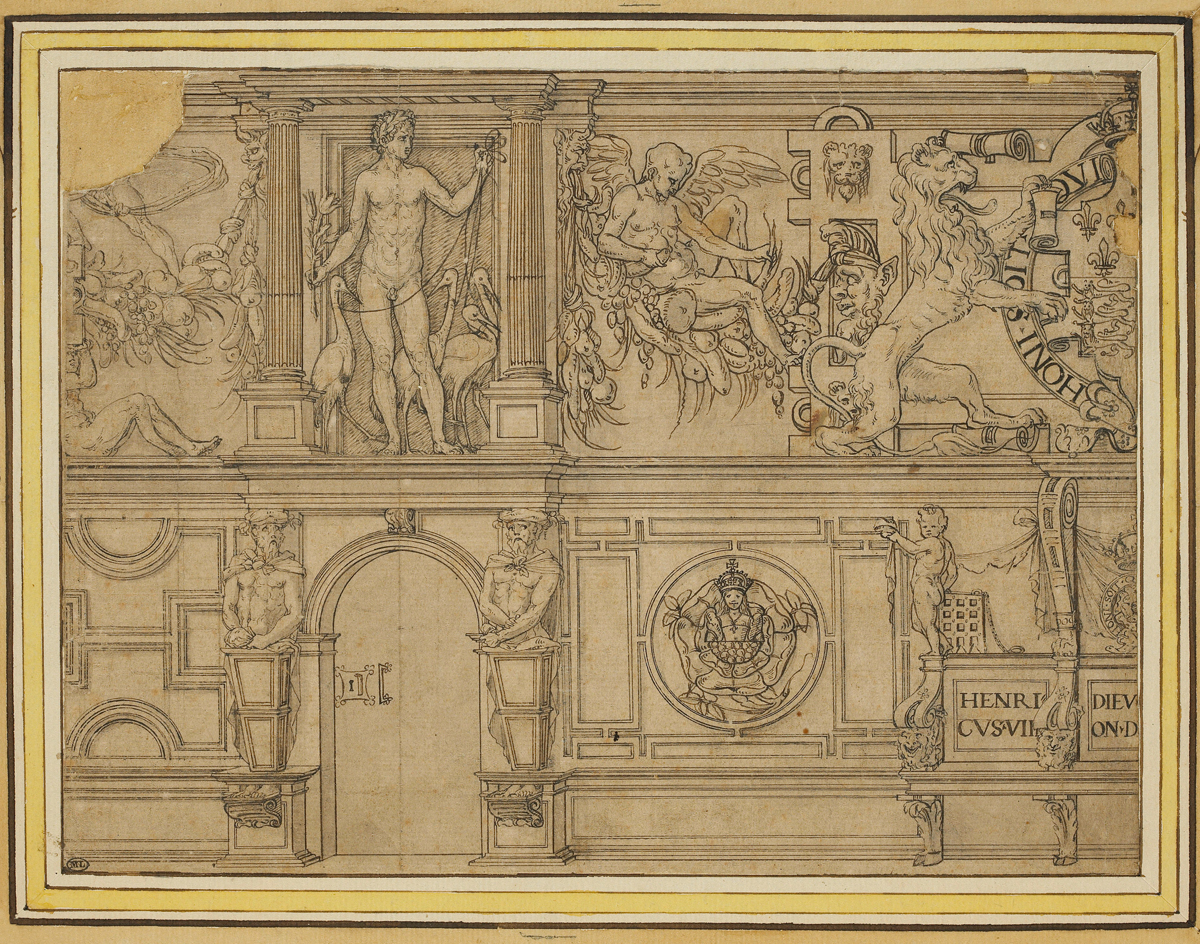

Attributed to Nicholas Bellin of Modena, Design for an Interior with the Arms of Henry VIII—Whitehall, ca. 1545. Pen and ink on beige paper, 8 1/16 × 10 13/16 inches. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource.

The red-and-white bloom of the Tudor Rose is the clearest illustration of how a fiction—or a faint, wavering line of succession—can be naturalized through enshrinement and repetition; we see it everywhere in the exhibition, in laboriously embroidered garments and plans for wildly ornate interior plasterwork. A heraldic device invented by Henry VII to represent the end of the Wars of the Roses, the rose was a brilliant public-relations graphic-identity move, shifting focus from his seizure of the throne to the momentous unification of the long-warring Plantagenet factions of Lancaster and York through his marriage to Elizabeth of York. As curator Elizabeth Cleland points out in her catalog essay, the insignia may have been inspired, in part, by Florentine botanical motifs. A length of gold and crimson velvet “furnishing textile” from the late-fifteenth to mid-sixteenth century, of the kind favored by the king, perhaps subtly incorporates the Tudor emblem into the floral and foliate patterning surrounding its central pomegranate, or perhaps it’s that Henry’s savvy flower echoes and aligns itself with the graceful designs of luxury imports, underscoring the importance of such goods—as both aesthetic and political ballast—to this cosmopolitan court’s fledgling identity. (The publication accompanying the exhibition is invaluable, bringing the significance of individual objects into focus.)

Furnishing Textile, late-15th–mid-16th century. Silk and metal thread, 10 feet 5 1/2 × 68 inches. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A century or so into Tudor rule, a dizzyingly intricate Elizabethan engraving uses the rose to structure an arcane genealogical map, or to rewrite history, omitting Henry’s Welsh origins and his descent from so-called “bastard” royal lines. Jodocus Hondius’s The Union of the Roses of the Famelies of Lancastre and Yorke, With the Armes of Those Which have Been Chose Knights of the Most H[o]norable Order of the Garter from that Tyme unto This Day 1589 distracts from his questionable lineage with a labyrinth of petals, recording within them all those admitted to the highest chivalric order during the Tudor period, as though to retroactively shore up the authority of the founding monarchs, who float like gods at the diagram’s top.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen.

Arriving in the roiling wake of Elizabeth II’s death (or just as the waters were beginning to calm), when the obsession with the royal family and the cultural preservation of the English monarchy has come under heightened, heated review—or so it seemed on social media in September—the show is perhaps accidentally well-timed. While it wisely does not try to say anything about the present, in moments it shines a tiny, flickering light on the grasping origins of a certain officious vulgarity that endures, protected by intractable flowery sentiment.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England, installation view. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen. Pictured, center: Hans Holbein the Younger, Edward VI as a Child, probably 1538. Oil on panel, 22 3/8 × 17 5/16 inches. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

It was Hilary Mantel’s passing two weeks after the queen’s, though, that was more on mind as I angled myself between those taking surreptitious pictures, and behind those getting too close, to see the prime attractions of the show myself. The author’s sublime literary depiction of its era in her Wolf Hall Trilogy, through the tenebrous lens of royal adviser Thomas Cromwell’s thoughts, holds up in the presence of works she describes or alludes to; Hans Holbein the Younger will always, for me, evoke the unembroidered atmospherics and oppressive sense of paranoia her work achieves. Portraits by the painter, an ambitious character in Mantel’s vision of Henry VIII’s court, stand out in The Tudors for their unrivaled realism and nuance and for their poignant, unintentional contrasts in realization and scale. Mantel recounts Holbein’s ingratiating presentation of his New Year’s gift to the king, which hangs now at the Met: Edward VI as a Child (probably 1538), which shows the long-sought heir and future king—Henry’s son with Jane Seymour, who would die at age fifteen—as a robust and milky prize. In Anne Boleyn (ca. 1533–36), the downcast queen is drawn in chalk on pink paper, wearing a nightdress, already a ghost—a melancholic effect also mostly undisturbed by the robot voice. (Cromwell was the infamous architect of Boleyn’s demise.)

Attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Elizabeth I (The Rainbow Portrait), ca. 1602. Oil on canvas, 50 3/8 × 40 inches. Courtesy the Marquess of Salisbury, Hatfield House. © Hatfield House / Bridgeman Images.

That brief queen’s daughter does indeed appear a victor here, ushering in a new style and decorative regime—long after Cromwell’s own beheading. The exhibition’s Elizabethan final stretch presents this queen in large-scale portraits, a supernatural force, more curlicues and symbology than flesh and blood. The monarch is recognizable by her red hair and rigid, wasp-waisted resplendence, but the tributes—likely commissioned by nobles to curry favor with her majesty—do not agree on a likeness.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Queen Elizabeth I (The Ditchley Portrait), ca. 1592. Oil on canvas, 95 × 60 inches. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

In a stiff and strangely proportioned full-length canvas attributed to the workshop of Nicholas Hilliard (ca. 1547–1599), her body is draped and upholstered against busy planes of competing patterns and filigree. The Ditchley Portrait (ca. 1592) by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger is, in contrast, a less busy, esoteric marvel—she stands on a map of Southern England beneath a sky of dueling extremes, with several Latin mottos extolling her Christian benevolence in the background. Especially for those who watched last summer’s better-than-usual Starz series Becoming Elizabeth, sadly canceled after one season, “She can but does not take revenge” seems the best of them. The Tudors, with its rich gloom and wealth of exciting even if well-trodden narrative threads, adds transfixing detail to whatever historical knowledge—or period-piece familiarity—one might have of the time. When the crowds die down, I’d say it’s an ideal show for both edification and wandering, daydreaming perusal.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull salon in New York. She writes art reviews regularly for the New Yorker and is a contributing editor for Artforum.