Johanna Fateman

Johanna Fateman

Desolation and devastation—but also pleasures—of the body, in an exhibition of new paintings.

Tracey Emin: Lovers Grave, installation view. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: White Cube (On White Wall). © Tracey Emin.

Tracey Emin: Lovers Grave, White Cube, 1002 Madison Avenue, New York City, through January 13, 2024

• • •

In Tracey Emin’s new show, gracefully or crudely outlined bodies are beached on islands of bleeding brushwork, float in faintly rendered rooms, or disappear into tangled, hazy spaces. Lovers Grave, as the exhibition is titled, fills White Cube’s new location on the Upper East Side with a cycle of commanding large-scale paintings on floors one and two, while the cellar gallery presents a dozen small pictures with faint ribbons of penciled script along their bottom edges—handwritten phrases that seem like captions more than titles—lending them an unguarded, diarylike presence. Her first New York solo exhibition in seven years contains no surprises, visually speaking. The work’s airy urgency, its naked expanses of unprimed canvas and naked figures, the calligraphic or slashing brevity of Emin’s line: all are familiar. Still, it feels fresh. With characteristic directness, the British artist unfurls the most recent chapter of the life story that legions of admirers (and, these days, fewer skeptics) have been following for many years.

Tracey Emin: Lovers Grave, installation view. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: White Cube (On White Wall). © Tracey Emin.

Three decades ago exactly, Emin, whose messy mastery of the conceptual overshare distinguished her from the coyer provocateurs of her YBA cohort, had her first solo show, at White Cube’s flagship Duke Street gallery. The autobiographical installation My Major Retrospective 1963–1993—an exploded memory box composed of such things as family photos, keepsakes, love letters, tiny reproductions of art-school paintings, and the first of her text-based handmade quilts—suggested, with its wistful as well as tongue-in-cheek title, that she thought her career might have already crested. In fact, the most celebrated, scandalizing works that established her reputation were still on the horizon, including the 1995 tent colorfully appliquéd with names, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, or My Bed, from three years later, the unmade readymade (short-listed for the 1999 Turner prize) that memorialized a four-day, post-breakup spiral of immobile despair. Lovers Grave is now proof of her tenacity—in more ways than one.

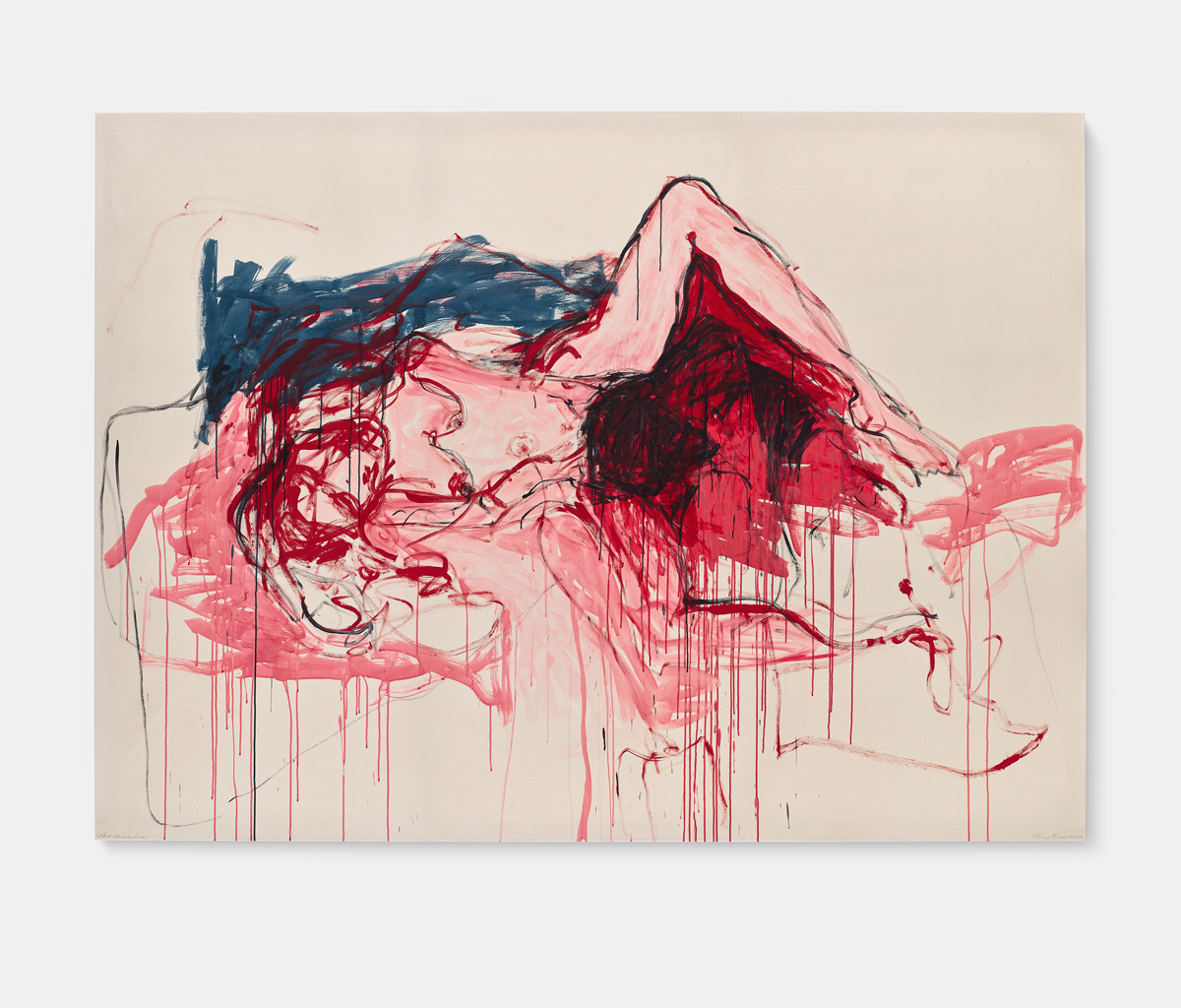

Tracey Emin, And It was Love, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 80 7/8 × 110 1/16 inches. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Tracey Emin.

The nine-foot-long horizontal painting on the wall facing the gallery’s entrance, showing a nude, spread-legged, with a black and crimson puddle, mass, or void at her crotch, might be read—as many, or all, of the works on view could be—through the lens of the British artist’s life-altering health crises of recent years. A 2020 diagnosis of aggressive bladder cancer required the removal of the organ as well as much of what surrounded it. (In her weekly column for London’s Evening Standard, and elsewhere, the artist has been devastatingly frank about the ordeal and its ongoing toll.) Pain is not the whole picture, though. Upon closer look at the canvas, And It was Love (all works cited are from 2023), the dark clot of gestures at its center seems to be a lover’s head, the crooked pose of the central figure a contortion of ecstasy.

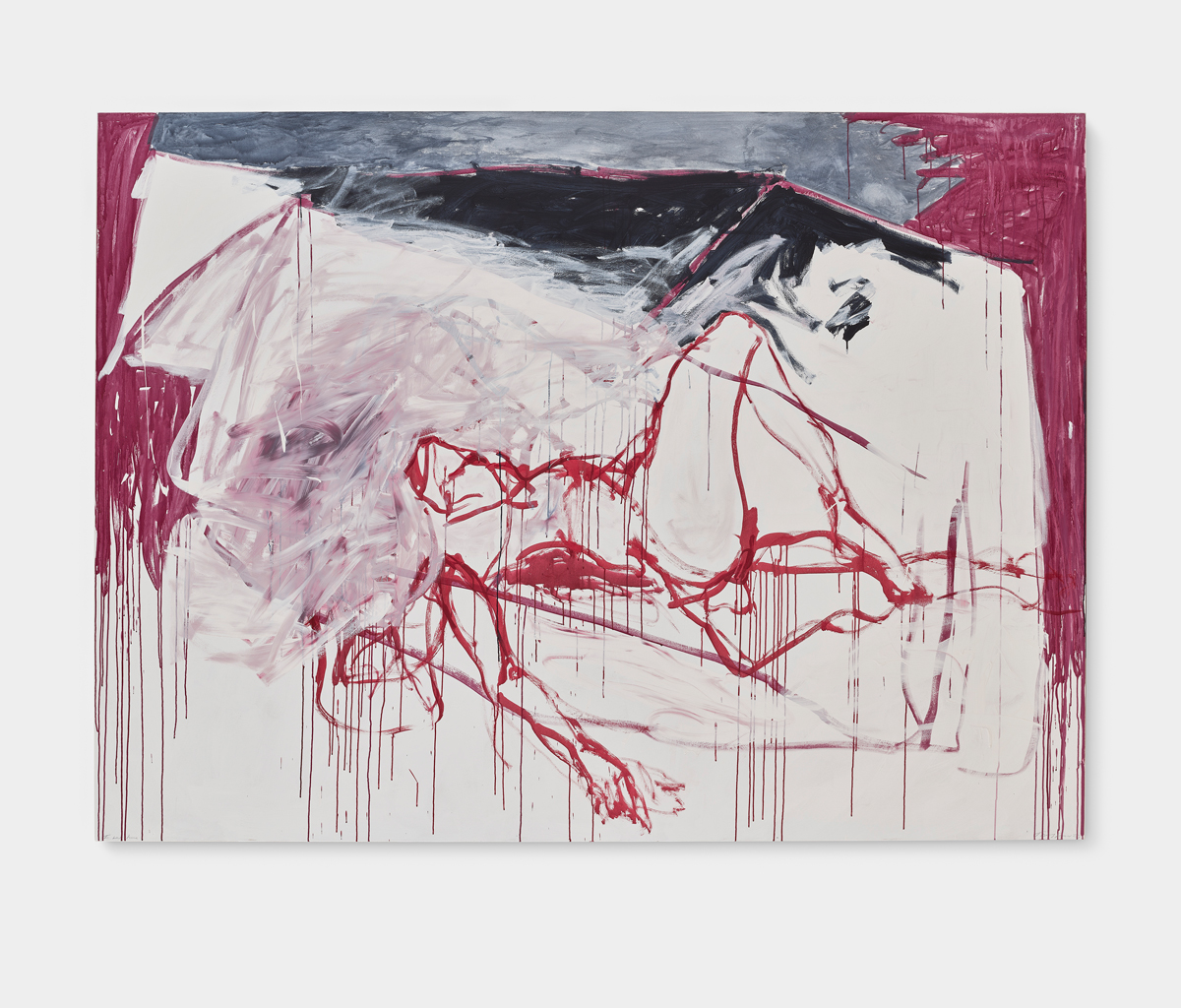

Tracey Emin, And I said Eat me - Bring me back to Life, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 59 15/16 × 59 15/16 inches. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Tracey Emin.

Nearby, And I said Eat me – Bring me back to Life depicts the same act from the same fly-on-the-wall vantage. The essence of Emin’s likeness, of her face and her long legs, is detectable (she has said that the woman she always paints is herself), but her form is drained of color in the composition’s pale turbulence of blue and gray lines, a cloudy palimpsest unanchored by red. The couple in a third iteration of—I think—a similar scene, It Felt Like you Loved me, are shown as fragments, limned in a bloody hue like snaking arteries, then mostly redacted with white. Things are often scribbled over in Emin’s work. I went home features a single figure, her head effaced in a smudged flurry, reclining beneath the dark roof of a partially articulated, or disintegrating, house (an unusual architectural presence among these drifting, setless scenes).

Tracey Emin, I went home, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 80 7/8 × 110 1/16 inches. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. © Tracey Emin.

The emotional force of Emin’s exhibition is amplified by her (latest) experience of life’s extremes (the delirium of new love, great sex, a brush with death), and intensified by her commitment, for now, to painting, a medium she has in the past circled with suspicion and wrestled with. It was as a teen, through her adoration of David Bowie, that she found her modernist soulmate Edvard Munch—the pop star’s imitation of Egon Schiele’s angular, alienated poses on album covers led her first to the Austrian Expressionist and then to the Norwegian painter of The Scream. Both artists have long loomed large in her work, their influence reflected in her confident line and theme of desolation—though, in her treatment of the transhistorical subject of the nude, she evokes other things as well, such as cave painting and the pictographic porn of the bathroom-stall vandal. In Lovers Grave there’s a pronounced if desultory engagement with AbEx, too, with curtains of drips becoming easy, sometimes unexciting backdrops for figuration—but there’s a hit of wry, emasculating disdain in her conscription of that ejaculatory style for compositional filler that saves it.

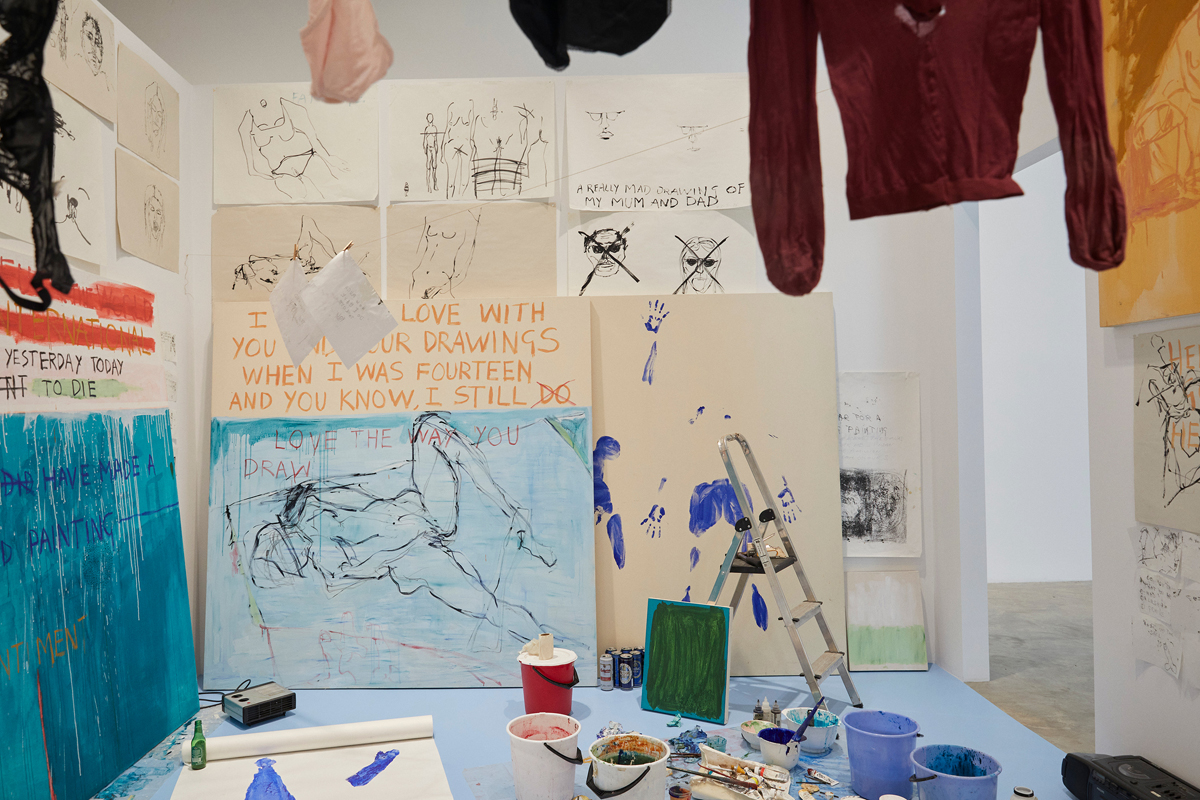

Tracey Emin: Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, installation view. Courtesy Faurschou. Photo: Victoria Hely Hutchinson. © Faurschou.

A well-timed illumination of painting’s vacillating role in Emin’s historically hybrid practice is concurrently on view—not so far away, but not exactly in convenient proximity either—in Greenpoint. The private museum Faurschou presents, for the first time in the United States, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, the preserved environment of the artist’s three weeks locked in a room—a small painting studio with a bed—within a Stockholm gallery in 1996. Viewed through fish-eye lenses, Emin could be observed, working naked, in an endurance-based encounter with the art form she had foresworn six years earlier after a traumatic abortion (“I could have easily died”). The evidence of her activity includes, as in the littered life raft of My Bed, the undoctored traces of living (beer bottles, argyle socks on a clothesline) and also a range of figurative works. Peering through the cordoned-off doorway, I could spot a Klein-blue body print, Emin’s self-directed take on the French artist’s Anthropometry series, for which young women were his living paintbrushes; a dashed-off canvas of a masturbating woman, emblazoned with the confession (addressed to Schiele, maybe, who also favored such explicit views, granting them a kindred attenuated elegance), I FELL IN LOVE WITH YOU AND YOUR DRAWINGS WHEN I WAS FOURTEEN . . . ; and a cartoony image of a couple fucking accompanied by the text IF I HAVE TO BE HONEST I’D RATHER NOT BE PAINTING. Elsewhere, in drawings pinned to the walls, there are crossed-out faces and body parts—early examples of Emin’s tendency to represent the sexed body sous rature.

Tracey Emin: Lovers Grave, installation view. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: White Cube (On White Wall). © Tracey Emin.

If Exorcism stands as a physical record of Emin’s process, her restless, inconsolable presence still palpable, like a time-lapse hologram in the empty vignette, I think she has, after so many years, achieved the same thing more efficiently, more powerfully, with the stark tumult and unrelenting reclining nudes of Lovers Grave. There’s an unjoking, unapologetic expressionism, steeped in art-historical precedent but floating free from it too, that has little to do with notions of self-portraiture or even with the particulars of a self. Emin has, of course, succeeded in telling her personal story—in detail, in various ways—but she now seems to be more in the terrain of the living paintbrush, the body that makes a painting with and of itself.

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and musician in New York.