Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

A chronicle of J Dilla’s innovative beats and samples.

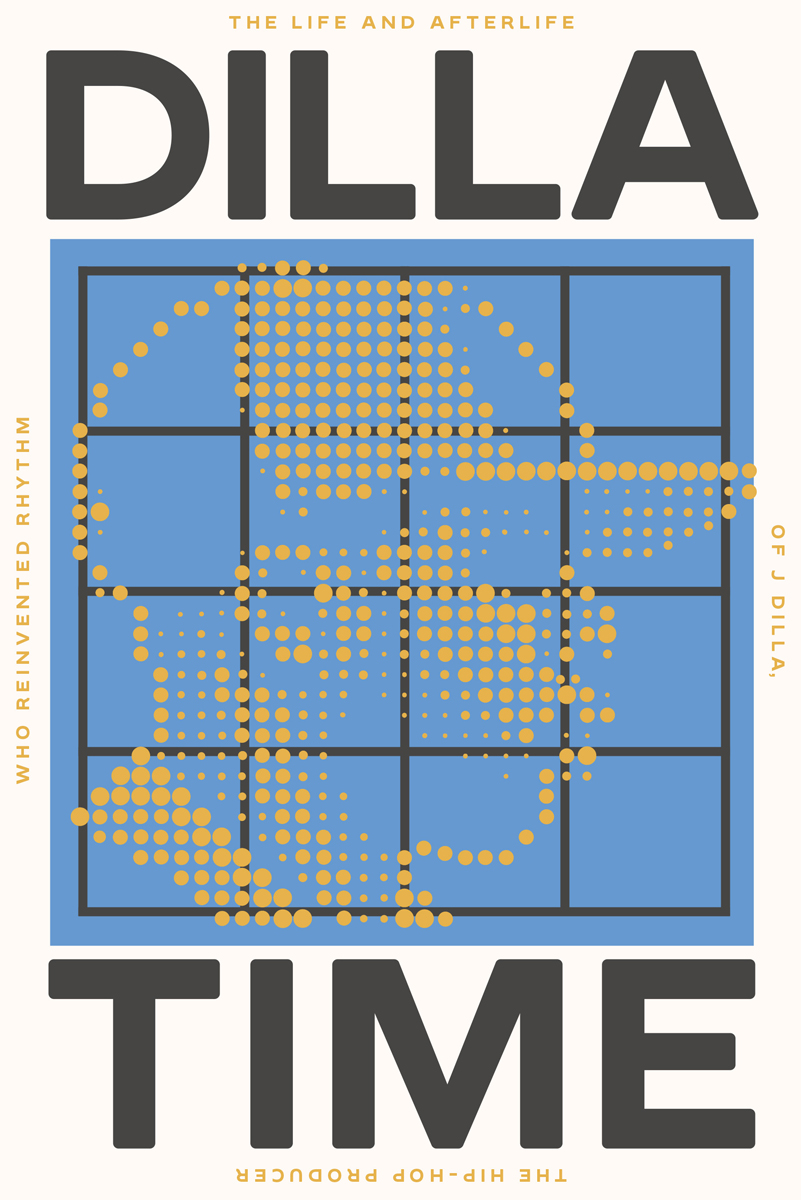

Dilla Time: The Life and Afterlife of J Dilla, the Hip-Hop Producer Who Reinvented Rhythm, by Dan Charnas, with musical analysis by Jeff Peretz, MCD, 458 pages, $30

• • •

There is a dogged tendency in music criticism to focus on lyrics. The words of singers are treated as both the target and source of meaning, the bit that demands unpacking, even though, as words, they are closer to self-evident than anything else in a song. Gently, I want to suggest that popular music is a wild cloud contained by recordings that invite repeated listening, but rarely because of words. Popular music exists first as sound. Hills? Dying? These are they.

Dan Charnas’s Dilla Time is a music book that’s actually about the stuff of music. The late producer J Dilla, born in Detroit as James Dewitt Yancey, in 1974, changed how music moves. Dilla died at the age of thirty-two, in 2006, due to the combined effects of lupus and a rare blood disease known as TTP. In the twelve years he was active as a producer, starting in 1993, he expanded the emotional range of hip-hop and created a small library of lodestones. De La Soul’s “Stakes Is High” (1996) is a personal favorite, and Dilla had a huge hand in D’Angelo’s Voodoo (2000), an album that sits near God.

If you’re looking for a quick way to learn what Dilla sounds like, try anything recorded by Slum Village, the group he cofounded in the mid-nineties with his friends T3 and Baatin. His better-known songs include Common’s “The Light” (2000) and Erykah Badu’s “Didn’t Cha Know” (2000). Janet Jackson’s “Got ’Til It’s Gone,” produced by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, was “a conscious re-creation” of a Dilla beat. Dilla’s methods came not from playing in a band or writing songs but from sitting at home and sampling records with a drum machine. What he did with it was to change how people experience the most common time signature in pop (4/4), and, in the process, he created what Kanye West called “arguably, the best drums in hip-hop history.”

Listen to the intro of “Billie Jean”: kick drums on the first and third beats, snares on the second and fourth, a measure of four beats repeating. Like 99 percent of the songs you know, this is an example of 4/4 time. Starting there, Dilla introduced irregularity and detail without fully syncopating the rhythm (as in swing) or adding extra beats (as in, say, 5/4 time). He did what he did by shifting where the sampled sounds landed, very slightly. The pianist Vijay Iyer uses the term “microrhythms” to describe this kind of adjustment, and this flexible approach is part of what artist Arthur Jafa has called “Black intonation.” (Charnas cites both ideas here.) The small deviations of timing that Dilla introduced are an example of digital work that mimics the living vocabulary of musicians rather than emphasizes its own machine nature. (My word for this digital liveliness is flickering, which I’ve used elsewhere.) Digital recordings smear now in a way they didn’t in the nineties, and this isn’t just because the software and hardware changed. We hear time differently, and Dilla’s work is a part of that. Dilla slouched so that James Blake could fall over.

One Dilla production from 1995 illustrates how intense these small changes can feel. The Pharcyde’s “Runnin’ ” has a kick pattern that takes twenty bars to unfold before looping again. It doesn’t sound precisely like live music, but we sense the programmer and hear the joy in his decisions. Dilla floats a sample of an acoustic guitar from a samba record over the drums, nudging the rhythm into its own edges. Pharcyde member Fatlip, though, hated the drunken kick pattern so much that he erased it. He was right to hear Dilla’s differences as significant—he was just in the minority opinion then, as he would be now. As Charnas reports, his bandmate Tre tackled Fatlip and almost pulled a knife on him. “That kick was perfect . . . We’re not changing it,” he said. “That’s your signature.” The Pharcyde rerecorded the kick and restored the beat as Dilla had given it unto them.

Musicologist Jeff Peretz helped Charnas create charts that illustrate where Dilla’s programming choices land within the grid of a time signature. Peretz did not prevent Charnas, however, from overselling Dilla’s innovations and crushing out a little too hard. Charnas peppers sentences with unfortunate framing phrases like “Before J Dilla, our popular music . . .” and “The hard part for musicians . . .” Musicians spend much of their time moving gestures slightly before and after the beat, even in genres that fall outside the sphere of this book. Spend a night with some classic Nashville records and listen closely: Who’s ahead? Who’s behind? Give it an hour and you will have filled out a few index cards.

But I get it. Charnas isn’t wrong about the musicians who wanted to hear time the way Dilla heard it. Questlove and D’Angelo changed how they played because of Dilla, and drum machines are unique in their way of corralling time. Using the editing features of the Akai MPC3000, Dilla was able to move individual samples—kick, snare, bass, harp, bird squeal—forward or backward, measuring these moves in what he called “baby hairs.” This is not hard to spot if you cue up a Dilla production like Common’s “Dooinit” (2000). Each sound you hear lands a few milliseconds before or after where an element would usually fall. Dilla pulls your attention toward the atoms of a song and then asks your body to negotiate the gaps between them.

Many of his choices are easier to feel than they are to describe. You are frozen in place and zapped awake, an almost narcotic rewiring. This is a serious departure from the first generation of hip-hop records, which wanted you to get up and dance. Dilla wants you to sit down and freak out. His snares land early and his kicks land all over the place. Every element is proximate but not fixed, like a box of blueberries spilled across the floor. Dilla and T3 called this rhythmic feel “simple-complex.”

Dilla began producing in the nineties with Slum Village but quickly moved into a partnership with one of his elders, Q-Tip. Dilla also worked extensively with Questlove and D’Angelo on Voodoo, though the specific tracks he worked on didn’t make the album’s final cut. He was around for the entire process, and the sluggish, narcoleptic sound of the album was an intentional echo of his beats. When he looked at the album credits, Dilla asked his friend, DJ House Shoes, “Where’s my name?” That combined air of musical elevation—Questlove called him “our Dalai Lama”—and bad timing dogged Dilla’s career. One of his greatest works is Donuts, an album Dilla didn’t even think of as an album. A beat tape of short fragments, Donuts was expanded and completed by Jeff Jank of Stones Throw while Dilla was in the hospital. It was released only three days before his death in February of 2006.

After Dilla became posthumously huge, Charnas quotes journalist Jefferson “Chairman” Mao as thinking “And where did all these J Dilla fans come from?” I admit to the same surprise, and a slight embarrassment, because I had always thought Dilla did great work but had never taken stock of what made it distinct. Dilla Time might read like a brilliant two-hundred-fifty-page book trapped inside a solid four-hundred-page one. But reliving Dilla’s rise through it allowed me to feel a bit of what his friends must have felt, watching a man who arranged all the Cokes in the fridge symmetrically—“like a graveyard,” Erykah Badu said—make a fully formed song in minutes, and then sit back down, surrounded by towers of records he knew, and loved, and sometimes improved.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.