Sasha Frere-Jones

Sasha Frere-Jones

Remaking rock as they saw fit: a box set revisits the Athens band.

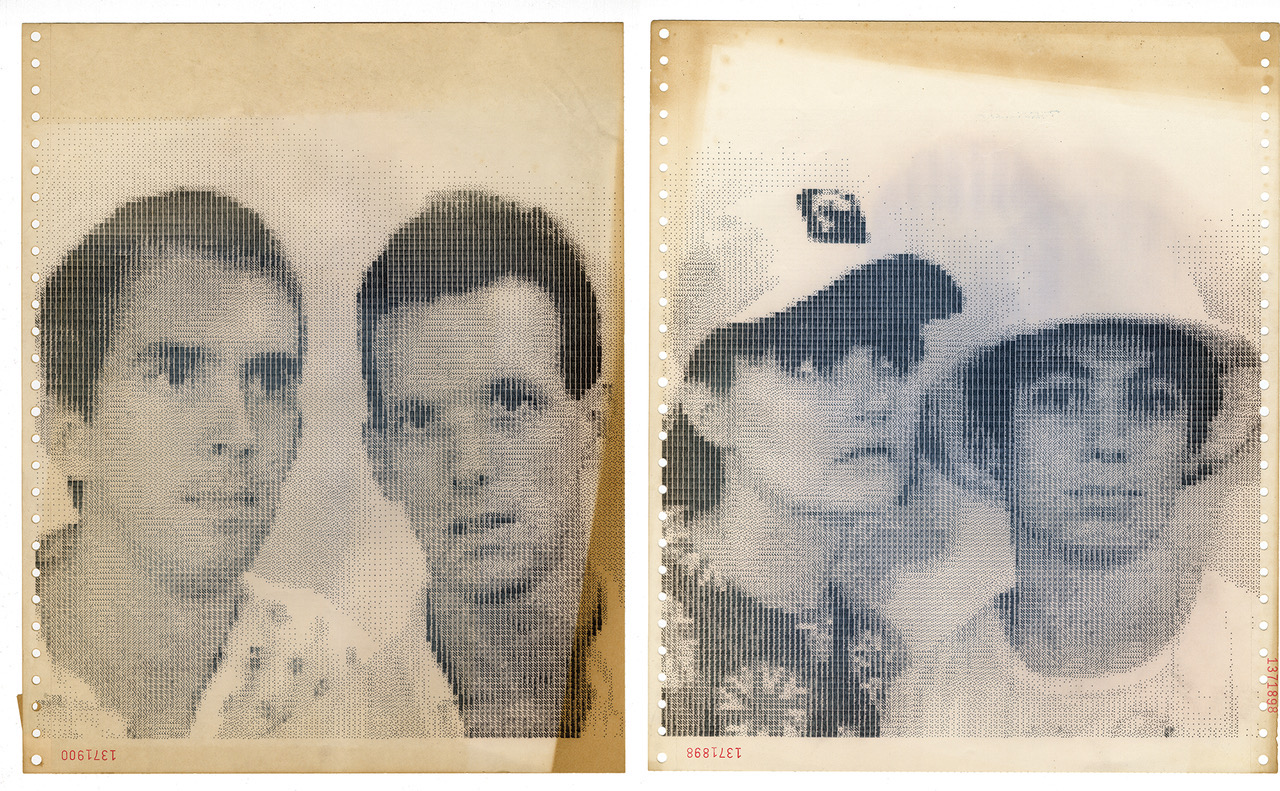

Randy Bewley, Michael Lachowski, Vanessa Briscoe Hay, and Curtis Crowe of Pylon. Two panels of dot matrix ASCII prints made at Playland in Times Square, c. 1980. Image courtesy Michael Lachowski. (Note: Vanessa and Curtis traded their hats for this image.)

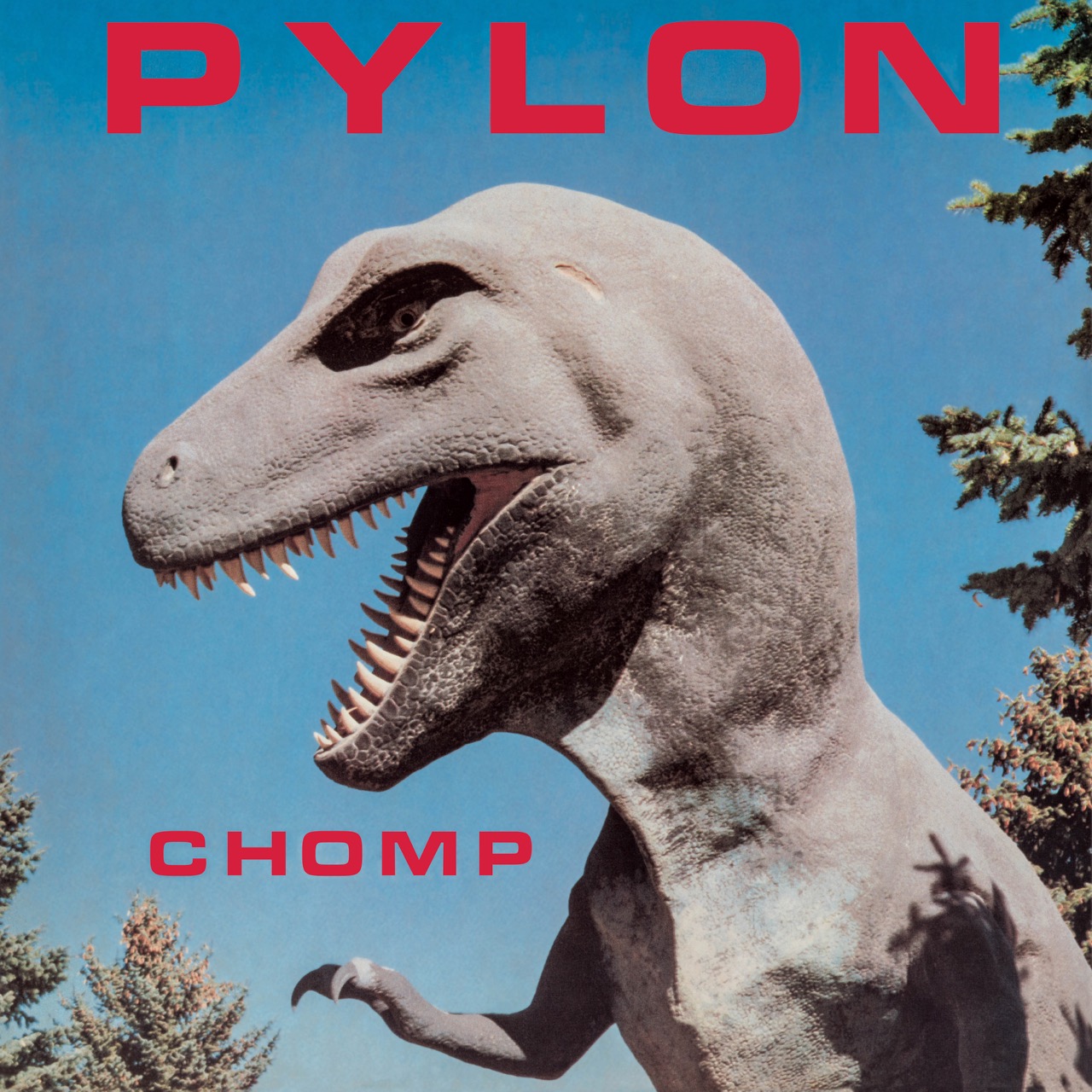

Pylon: Box, New West Records

• • •

In the summer of 1978, Michael Lachowski was working in the DuPont textile factory outside of Athens, Georgia. He was stationed in a large, clean concrete room with the warping unit, an aquamarine hodgepodge of machines that pulled colorless synthetic fibers from a rack of spools to the other side of the room, where they were wound onto one big spool known as the “beam.” Michael’s friends, Vanessa Briscoe Hay and Curtis Crowe, had jobs in the carpet fiber division. The plant was covered with a collection of gently pointed warnings printed on plastic signs. Certain areas were marked off with traffic pylons: black base, yellow body, red tip. These were pristine, though, and shiny. Familiar but off.

All three had met when studying art at the University of Georgia. That fall, Lachowski and roommate Randy Bewley started practicing bass and guitar lines over and over in their apartment. They’d never played before, but they were finding a tight and forceful sound. They moved their rehearsals to Lachowski’s studio, a loft on the second floor above a sandwich shop. Crowe was their landlord and upstairs neighbor. Curtis liked hearing Michael and Randy rehearse, finding the repeated figures soothing. After a few weeks, he walked downstairs to join them on drums. A band seemed to be happening, so a couple of singers were auditioned. Nobody clicked until Briscoe Hay tried out. She was brought into the band immediately and the name Pylon was established. Crowe had been hosting live shows in his third-floor loft, informally named the 40 Watt Club. Eventually, he and his friend Paul Scales started booking acts in a space down the street (above Yudi’s, a different sandwich shop) and turned it into a commercial concern with the same name. The 40 Watt Club is now the most famous rock club in Athens.

Box contains four LPs: the first two Pylon albums, Gyrate (1980) and Chomp (1983); as well as their first demo tape in its entirety, and a collection of singles and unreleased songs. These recordings demonstrate how powerful the idea of punk was as liberation, not in the sense of political emancipation but as a license to start from scratch. The only member of Pylon who already knew how to play an instrument was Crowe, and his experience on drums was limited. Pylon’s time as art students familiar with conceptual directives prepared them to remake rock as they saw fit. They learned to play with and against one another and wrote songs that were trim, dangerous, curved, proper.

Pylon. Image courtesy New West Records. Photo: Brian Shanley.

Pylon’s specialty was spare, danceable rock—familiar but off. Briscoe Hay loaded her personality into every vocalization, some tonal, some just hopped-up speech acts. In “Recent Title,” she snarls out the truth. “I can do anything that I please” is her American theme, followed by the chilling punchline: “I can knit, I can eat.” This was typical of Pylon’s project, to start with music that hit hard but didn’t explode, and line it up with a human voice that barked but was never impolite. The instrumental trio inside the quartet made music that banged evenly, like the warping machine, while Briscoe Hay sounded like a punk singer even when she was cautioning listeners in roughly the same language DuPont used for their safety signs. Working is no problem! Be prepared! Everything is cool! Read a book!

After playing around Athens for a few months, the band decided to make a dream come true: perform once in New York and get written up in New York Rocker. In 1979, this came to pass, though reality was better than the dream. After a gig at Hurrah, Glenn O’Brien described them in Interview: “These kids listen to dub for breakfast.” Their love of space presented as a formal echo of instrumental Jamaican reggae, a kind of music they’d neither heard nor heard of. In response to O’Brien’s comments, they wrote “Dub,” a heavy vamp that sounds like the scratchier side of Gang of Four. “We eat dub for breakfast!” was the chorus, if the song has one. This “Dub,” which was not, was the B-side of their debut seven-inch, “Cool,” which was.

That single’s cover was designed by Lachowski, as was Box and all of their other releases. Using Chartpak and Zip-a-Tone touch lettering, Lachowski deployed the Microgramma Bold Extended font, associated for years with the Star Trek: Star Fleet Technical Manual (a freak bestseller in the seventies). All Pylon releases have a word centered at the top edge, with one or two words near the bottom edge, and nowhere else. A single image lies between them, full bleed. For “Cool,” it was an engineer’s sketch of the pylon, highlighted with minimal use of a single color: red. Four-color printing is expensive! Art doesn’t need much!

Efficient and passionate and clipped, Pylon had no slow songs, no ballads, and no duds. There is a hint of disco’s propulsion in many of their tracks, including “M-Train,” which would be the A-side on any other single. Pylon wrote “M-Train” in their rehearsal space, during a brief moment of musical chairs. While Lachowski was in the bathroom, Bewley picked up his bass and left his own guitar face up on the floor, feeding back. Swapping instruments revealed how consistently every member of Pylon approached their minimalism, rendering symphonic swells with two notes the way an illustrator indicates the sky with a bent line. “I think you should give it away! / I think you should catch that train!” Briscoe Hay growls, sending an ex away.

The A-side of this 1981 single, though, is one of my absolutely favorite recordings. Written in one session, without revision, “Crazy” suggests that thinking about what you want to achieve, rather than what you can do, is central to the practice of popular music. Lachowski wrote Pylon’s lyrics before Briscoe Hay joined, but she wrote many of the lyrics, including “Crazy,” while she was in the band. Bewley cherry-picks a few notes and implies four chords with the bones of two. Lachowski’s bass swings along beside Bewley’s flanged guitar, and Briscoe Hay starts low with one word, “listen,” pronounced as “the SUN.” She softens her voice to deliver an accusation that could be a confession: “You’re funny and you don’t know why / you’re funny and you can’t even cry.” The guitar and bass move through different phases of reassembly, every verse plausibly the chorus. Briscoe Hay clicks into her beautifully strangled middle range and the song surges: “Your arms are shaking / and your feet are shaking / because the earth is shaking.” The song burns the object world and the mind and the heart into a single motion. She sings “nothing can hurt you / unless you want it to” and it’s the promise of life (or rock) itself. Briscoe Hay told me that, over the years, many fans have told her “Crazy” was their coming-out song. At the last Pylon show in 1983, available as Live, she introduced it by saying, “This is for the girls.”

After they played “Crazy” for the first time, at the 40 Watt Club, Briscoe Hay walked outside and found three young fans sitting on the sidewalk. One of them, Michael Stipe, nodded at the singer.

“I really like that new song.”

Four years after the release of Pylon’s single, R.E.M. covered “Crazy” for one of their own singles. Now, on Box, the original seven-inch version of the song is finally back in print. If that’s the only track you play for a week, don’t be surprised.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a musician and writer from New York.