Ed Halter

Ed Halter

Screengrabs, fabbing, and a cyborg torso: the ICA Boston dives into thirty years of web-influenced work.

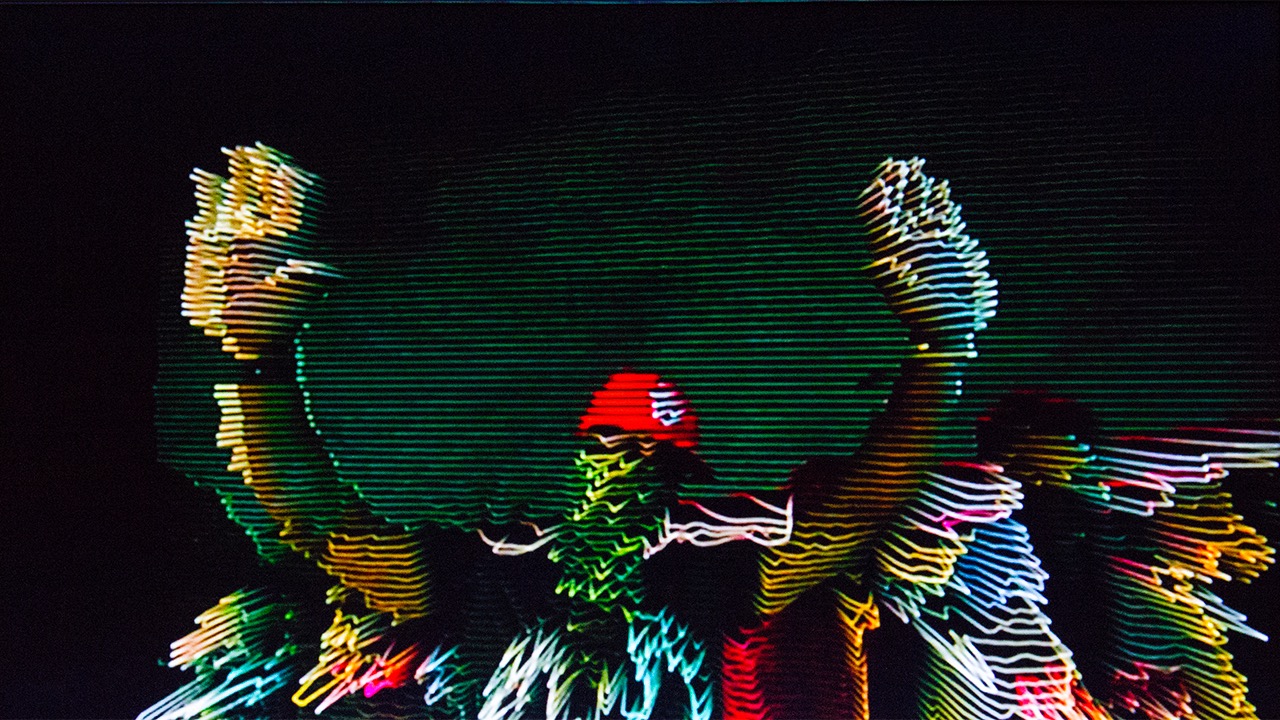

Nam June Paik, Internet Dream, 1994. Installation view. Photo: Caitlin Cunningham.

Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, ICA Boston, 25 Harbor Shore Drive, Boston, through May 20, 2018

• • •

The first artwork visible at the entrance to Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today at ICA Boston is Nam June Paik’s massive, cyberdelic video sculpture Internet Dream (1994). It’s a wall of fifty-two cathode-ray-tube monitors, all playing strobing streams of multicolored analog and early-digital graphics. The visual mood is hyperactive, joyous—a supersized variation on Paik’s early videospace romps, grooving on the ecstasy of the electronic signal, a paean to twentieth-century communication networks as extenders of human capability and new ways of seeing.

Paik’s sculpture is an effective reminder of the early techno-optimism of the internet, and an appropriate beginning to what claims to be, in the words of curator Eva Respini in her catalogue preface, “the first comprehensive institutional exhibition in the United States that attempts to approach the broad array of artworks both past and present surrounding the subject of the internet.” What’s inside the galleries, however, is actually something quite different: an enjoyable, accessible showcase of some of the best contemporary artists working with digital processes and synthetic materials, supported by notable forebears from previous generations who operated with shared concerns.

Sondra Perry, Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation, 2016. Video (color, sound; 9:05 minutes) and bicycle workstation. Courtesy the artist and The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Caitlin Cunningham. © Sondra Perry.

Visitors are treated to works by influential figures like Seth Price, Jill Magid, Cory Arcangel, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Oliver Laric, Sondra Perry, Trevor Paglen, Dara Birnbaum, and many other artists celebrated for revealing the aesthetic potentials of new technological developments. But while the show’s title suggests a historical survey of art made since the year that Tim Berners-Lee first proposed the World Wide Web, its selections tend to stray from any direct engagement with either the web, or even the internet more broadly, as a specific set of practices and cultures. Much like the internet itself, Art in the Age of the Internet is great at delivering high-quality, likable content, but not as good at providing a substantial context.

Rather than organizing itself chronologically, the exhibition is presented via five thematic sections: Networks and Circulation, Hybrid Bodies, Virtual Worlds, States of Surveillance, and Performing the Self. Older museumgoers (that is, those of us who remember art in the flip-phone era) will notice that these very familiar themes are standard categories that have long haunted the field of digital art. Like many past endeavors, Art in the Age of the Internet isn’t, ultimately, a show exclusively about the internet at all, but about even larger shifts in technology. It’s part of the long legacy of McLuhan-era investigations of art and technology, and a continuation of the old “new media” paradigm that was represented in the art world via exhibitions such as the Whitney’s BitStreams (2001), the work of organizations like Rhizome at the New Museum, and the activities of European media festivals in the 1990s and 2000s, now pursued under a more publicity-friendly but conceptually misleading moniker.

HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, thewayblackmachine (still), 2014–ongoing. 30-monitor video installation, approximately 80 × 30 × 10 inches. Courtesy the artists. © HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?

The show’s categories can work as useful frames. In a room devoted to Networks and Circulation, for instance, the show includes a number of pieces that emblematize the movement of information through the internet: Price’s Still, Five Hooded Men with Seated Man (2005), a sagging transparent banner bearing a pixelly screengrab from a terrorist hostage video; Aleksandra Domanović’s clever emailable sculpture, Untitled (mash-up) (2012), a PDF made of thousands of pages that, when printed out and stacked in a column, bears a transmitted color pattern on its bleeding edges; the collective HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?’s thewayblackmachine (2014–ongoing), another information-overloaded video wall displaying reedited and digitally processed footage from post-Ferguson social media, located via hashtags like #blacklivesmatter.

Gretchen Bender, American Flag, c. 1989. Fabric, 72 × 108 inches. Photo: Caitlin Cunningham. © Gretchen Bender.

Yet in the same room we find some excellent pieces that visually resemble today’s online aesthetics, but take their primary concerns from non- or pre-internet tech. Gretchen Bender’s American Flag (1989) is a good case in point: a fabric banner bearing an image from the opening of a television broadcast in which the Stars and Stripes have separated into fragments in the midst of a video transition. American Flag certainly expresses fascination with how the fungibility of images increased as editing techniques evolved from analog to digital, but it’s hard to see how it relates exactly to the circulation of those images through a distributed network. The same can be said for Dara Birnbaum’s cunning Computer Assisted Drawings: Proposal for Sony Corporation (1992/2017), an installation of unrealized design images, rendered in wireframes and separated into their CMYK colors, and Paul Pfeiffer’s John 3:16 (2000), a hovering-basketball video crafted from found TV-sports footage.

Dara Birnbaum, Computer Assisted Drawings: Proposal for Sony Corporation (detail), 1992/2017. Drawings on Plexiglas in custom aluminum frames, 16 parts. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. Photo: Caitlin Cunningham. © Caitlin Cunningham.

Networks and Circulation, however, remains relatively coherent compared to the Hybrid Bodies and Performing the Self sections, which veer off into general contemplations of these themes. Anicka Yi’s dreamy plastic-and-Plexiglas Fever and Spear (2014), Mariko Mori’s proto-cosplay photograph Subway (1994), and Lee Bul’s silicone cyborg torso Vanish (Jade) (2001) are all compelling on their own terms, but draw inspiration from new manufacturing techniques and science-fiction culture. Software, digital photography, digital video, digital printing, surveillance, robotics, fabbing, VR headsets—these are all manifestations of the post-computer age that occur again and again in the ICA’s exhibition, and yet none of these phenomena speak directly about the internet.

Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War (screenshot), 1996.

Art in the Age of the Internet’s most egregious oversight is the absurdly small number of web-based works in a show that is ostensibly structured around the history of the web. Only three websites appear in the galleries: two canonical, pioneering projects—Olia Lialina’s My Boyfriend Came Back from the War (1996) and JODI.org’s wwwwwwwww.jodi.org (1995)—are lovingly presented on vintage desktop computers, while Taryn Simon and the late Aaron Swartz’s search-engine critique Image Atlas (2012) is available for access on a more contemporary setup. The show’s website includes a single “artist project” by Lialina, a new essay entitled “An Infinite Séance 3,” which analyzes five websites that are not part of the exhibition’s official checklist. But the curation largely avoids a whole world of figures who have worked primarily online—from Heath Bunting to Mendi + Keith Obadike, to Guthrie Lonergan, to name only a handful. By side-stepping the internet itself in a show that is purportedly devoted to this very topic, the museum argues for an impoverished and self-serving definition of art, one centered on rare objects that can be displayed in the physical space of a gallery; Art in the Age of the Internet thereby avoids the most central challenge posed to art by the internet.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was recently published by Seven Stories Press.