Ed Halter

Ed Halter

Farewell frisson! The Guggenheim revisits the career of the

once-controversial photographer.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self Portrait, 1980. Gelatin silver print, 14 × 14 inches. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue, New York City, part one through

July 10, 2019

• • •

The starring role of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography in the culture wars of the late 1980s is one reason the artist remains inextricably linked to that historical period. Mapplethorpe’s death in 1989 due to complications from AIDS is another, stunting his chronology at age forty-two just before right-wing politicians helped make him one of the most famous artists of the late twentieth century. The Guggenheim’s Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now, a year-long exhibition presented in two parts, promises in its title a fresh take on Mapplethorpe, while arguing through its scale for his continued significance. The first phase of the show, surveying the full length of his career, draws exclusively from the museum’s substantial collection of his work; the second half, opening this summer, plans to place Mapplethorpe alongside other contemporary artists from the Guggenheim’s holdings.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon, 1982. Gelatin silver print, 19 3⁄16 × 15 ¼ inches. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

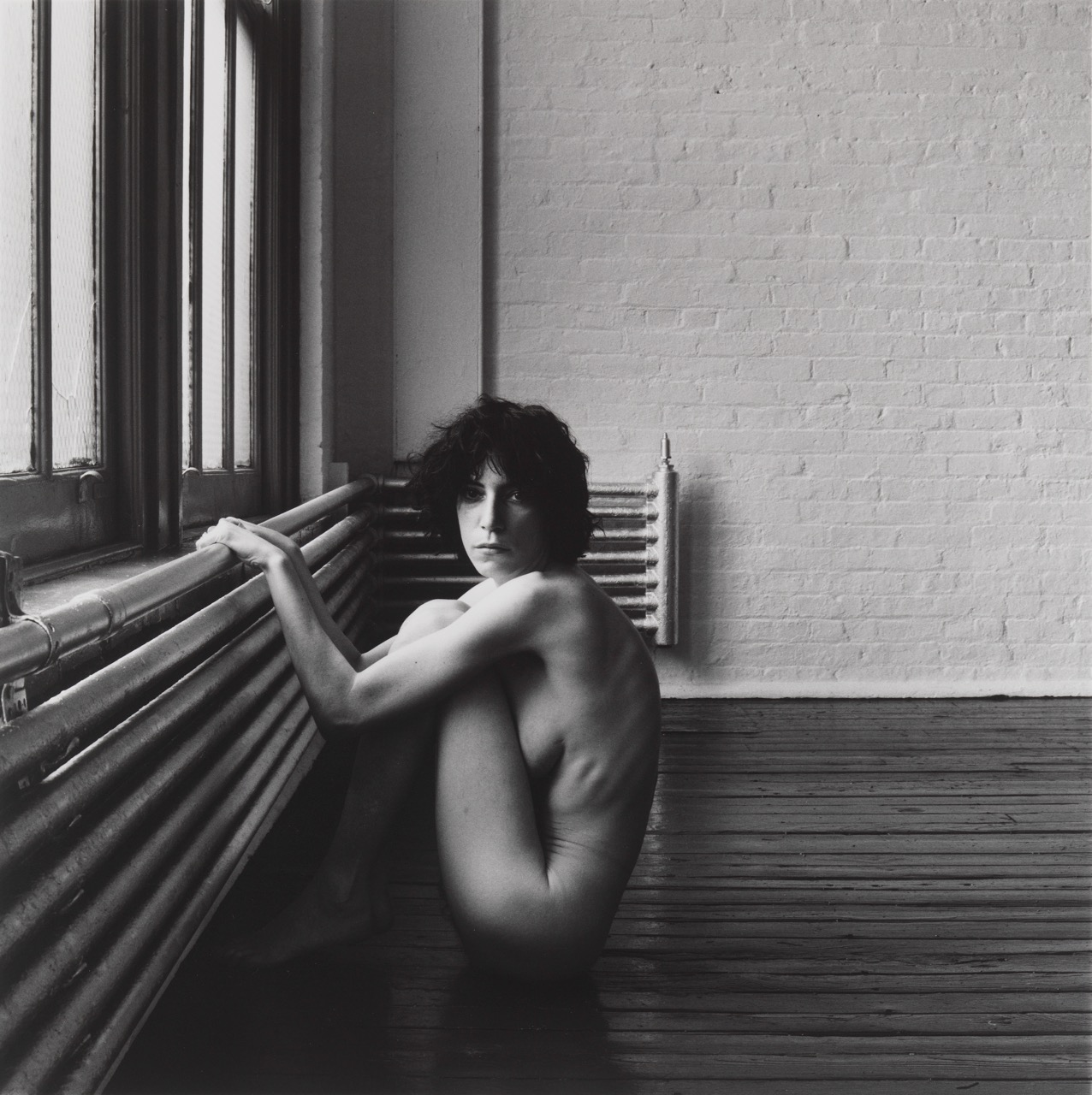

Despite the exhibition’s proposition, much of this first half brings us the Mapplethorpe we already know, showcasing prints of some of his most circulated images. Among the greatest hits on view are a number of his self-portraits, from an impish example taken in his late twenties (1975)—a flirty composition of arm, smile, and nipple—to later, more confrontational instances of the genre, in which he leers backward at the lens with bare ass toward the camera, leather bullwhip crammed into his rectum like a devil’s tail (1978), or poses Symbionese-style with a machine gun, black pentagram looming above his head (1983). There are portraits of bodybuilder Lisa Lyon and model Ken Moody, along with iconic pictures of Patti Smith (1976), Arnold Schwarzenegger (1976), Laurie Anderson (1987), and other notables. Toward the back of the exhibition, one finds a number of risqué pieces, including the notorious Man in Polyester Suit (1980), a study in textured grays with the pendulous cock of Mapplethorpe’s lover Milton Moore at its center. In 1989, this last image was brandished on the Senate floor by Jesse Helms, in an attempt to enrage the conservative base, after the opening of a partially government-funded exhibition that included the photograph. In 2015, while zillions of dick pics packet-switched their way through the internet, it sold for nearly half a million dollars at a Sotheby’s auction.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Patti Smith, 1976. Gelatin silver print, 13 ⅞ × 13 ¾ inches. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

If social media has diminished the impact of an artfully presented penis, thrill-seekers will be disappointed at the selection of explicit photos, which leans toward the titillating, sidestepping the most scandalous. Of Mapplethorpe’s gay BDSM-themed works, we are reacquainted with Jim and Tom, Sausalito (1977), which captures the couple’s watersports play in a rhombus of noir lighting, and Dominick and Elliot (1979), showing one man grasping the other’s crotch as he dangles upside down by his enroped ankles. What might once have struck viewers as field reports from the outer edges of extreme sexuality now appear sane, safe, and consensual, so that the quaint domestic trappings of Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter (1979) read as more prescient than ironic. Mapplethorpe’s most viscerally disturbing scenes cannot be seen in this exhibition: viewers here will not encounter a fist shoved wrist-deep into an ass, or a pinkie finger crammed into a penis, though Google will easily provide those to the curious. The gimp-suited Joe (Rubber Man) (1978), showing its subject crawling on all fours as if toward a mirror embedded in the photo’s frame, today seems less like a creature from our most unconscious desires emerging into the light of day, and more like an invitation for a selfie, allowing viewers to insert themselves into the fetish scene for the admiration of friends and followers. The image still reduces a human figure to its animal core, but puts it to work as another piece of livestock on the museum’s user-generated content farm.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter, 1979. Gelatin silver print, 13 15⁄16 × 14 1⁄16 inches. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Three decades of porn saturation since the artist’s death may have deadened the voyeuristic frisson once provided by photographs of plump genitals and rippling muscles, but no stronger feeling has replaced that once-intoxicating sensation. With this effect gone, what remains is Mapplethorpe the compulsive formalist, whose work only increases in its fussy studio-centered self-control as the 1980s progress. This aspect was more fruitfully explored in the Guggenheim’s previous Mapplethorpe exhibition, 2004’s Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition, which juxtaposed his work with mannerist art from the Hermitage’s collection, underlining the photographer’s role in pushing the postmodern penchant for art-historical quotation. In the monographic context of Implicit Tensions, Mapplethorpe becomes unmasked as a stylist whose greatest skill, in retrospect, was selling smartly packaged downtown subversion in exchange for uptown dollars and mass-market celebrity.

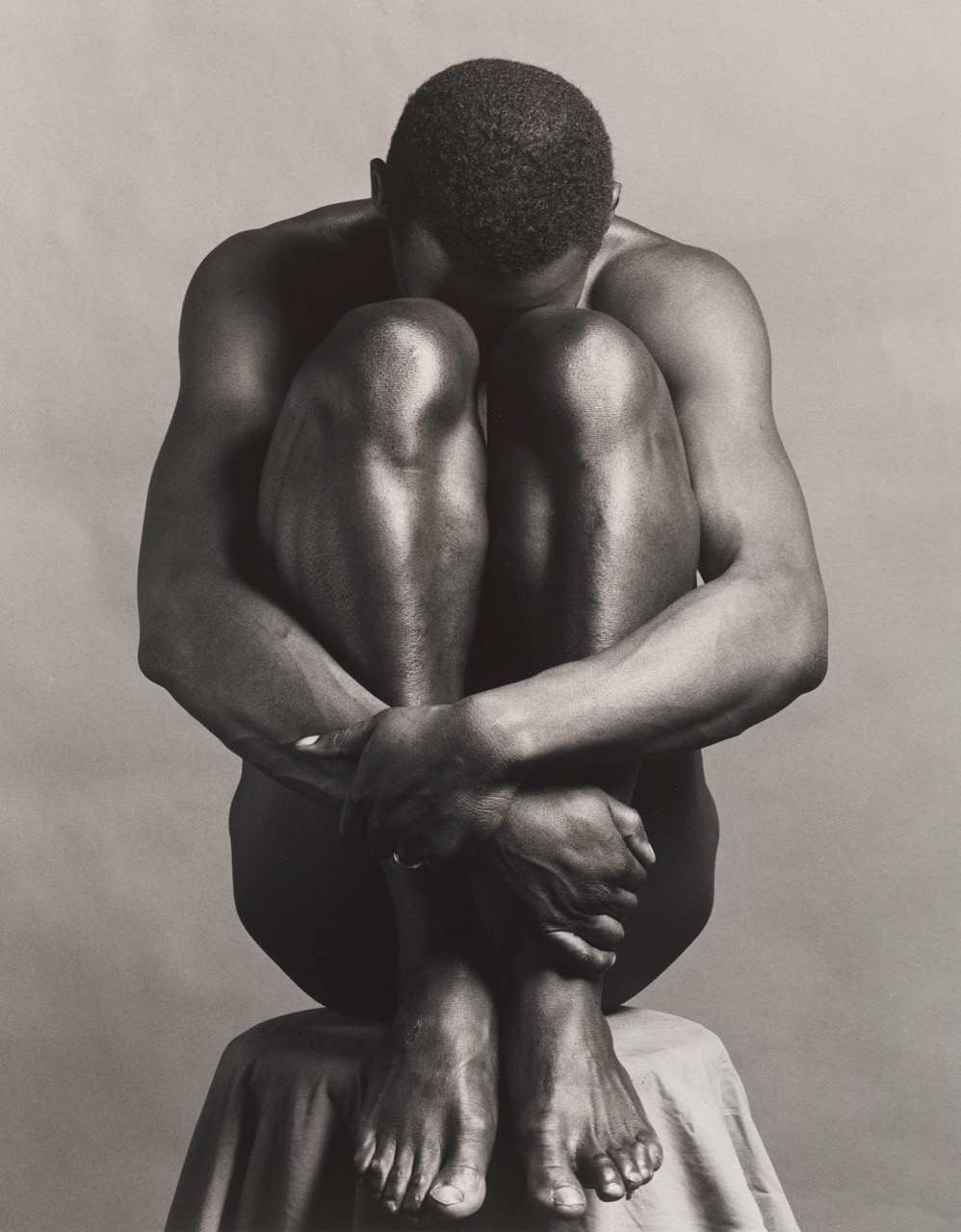

Robert Mapplethorpe, Ajitto, 1981. Gelatin silver print, 17 15⁄16 inches × 14 inches. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Sex may no longer stoke the engines of controversy, but race remains a potent trigger, as evidenced by recent firestorms involving artists like Dana Schutz, Kelley Walker, and Sam Durant. Mapplethorpe’s later output is dominated by erotic studies of black subjects, and the controversies surrounding his 1986 exhibition Black Males and the publication of his related portfolio The Black Book that same year were examined at length by numerous artists and thinkers on both sides of the Atlantic. The core critiques were hashed out by Kobena Mercer and Isaac Julien in the UK, and Essex Hemphill and Glenn Ligon in the US, with chime-ins from Edmund White, Wayne Koestenbaum, Judith Butler, and virtually every other intellectual who then had a stake in the politics of queer images. At the time, these critics were generally careful to defend Mapplethorpe’s erotics even if they denounced his obvious equation of blackness with hypersexuality, but even then, some were already framing Mapplethorpe as a talented opportunist. As early as 1986, Mercer called out “the fundamental conservatism of Mapplethorpe’s aesthetic style.” Theorizing the photographer’s modus operandi, Mercer wrote that “the black models seemed to become raw material, to be sculpted and molded by the agency of the white artist into an abstract and idealized aesthetic form,” pithily summing up the process as one in which “the black man’s bum becomes a Brancusi.”

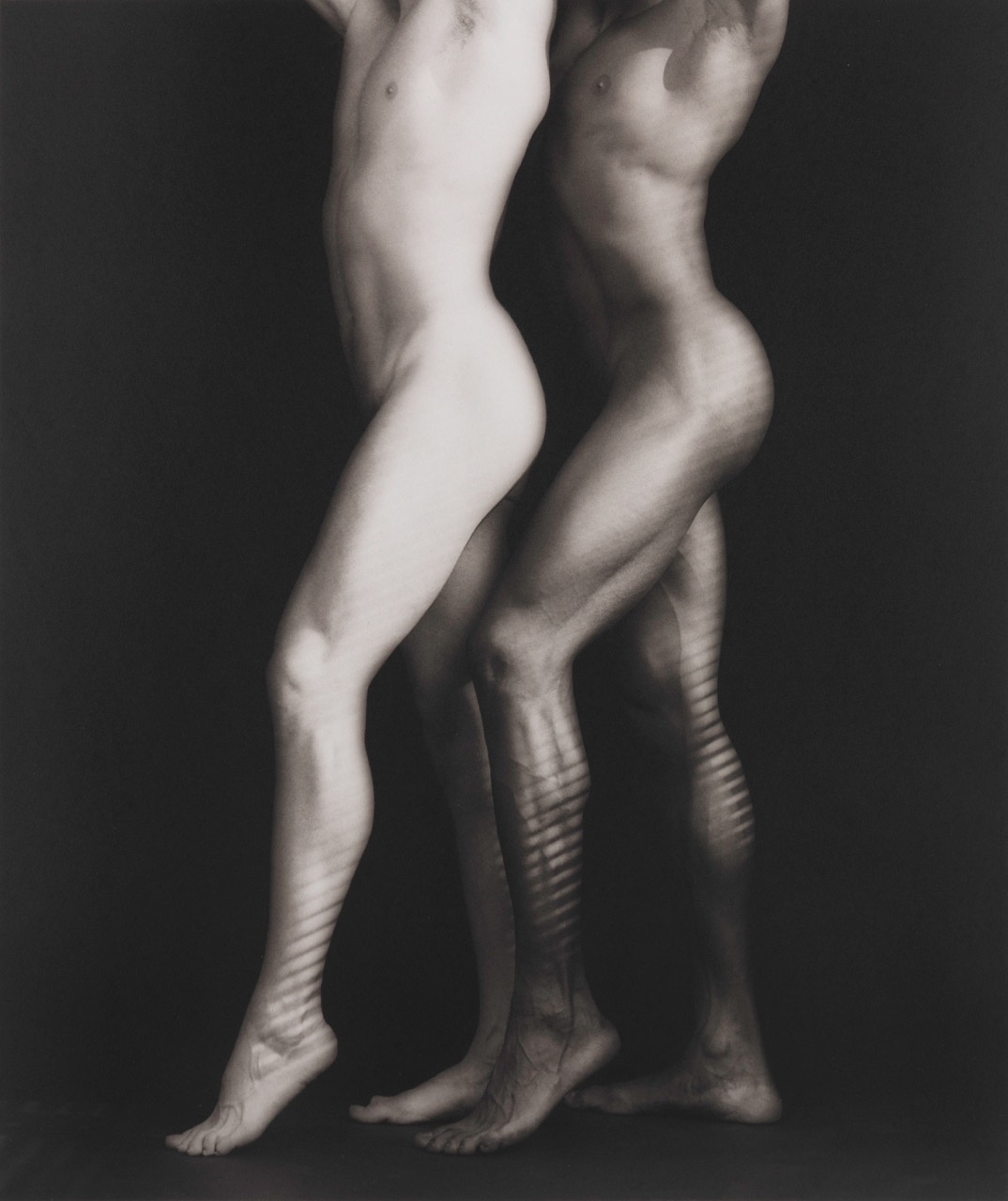

Robert Mapplethorpe, Ken and Tyler, 1985. Platinum-palladium print, 23 ⅜ × 19 ¾ inches. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Implicit Tension’s response to any potential backlash is to neither address nor hide Mapplethorpe’s questionable racial attitudes, at least in its first half. Perhaps the topic will be faced more openly in the exhibition’s second phase, which will include the works of numerous black artists from Mapplethorpe’s own time and ours. What’s already readable, however, is the way in which the power dynamics of Mapplethorpe’s leathersex photographs carry over into his later studies. BDSM is all about role-playing simple hierarchies: daddy and boy, master and slave, butch and femme, dominant and submissive. For Mapplethorpe, this fetish for binaries ultimately becomes mapped onto skin color, as most famously pictured in the exaggerated duo-tones of Ken Moody and Robert Sherman (1984) and Ken and Tyler (1985). In this, the photographer indulged one of our culture’s most shameful obsessions: the powerful desire for an absolute division between black and white.

Ed Halter is a founder and director of Light Industry, a venue for film and electronic art in Brooklyn, New York, and Critic in Residence at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. His collection From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, coedited with Barney Rosset, was recently published by Seven Stories Press.